Profits from rooibos tea are being shared with South Africa’s Indigenous Khoi and San People, in recognition of their contribution to its development.Credit: Mike Hutchings/Reuters

For at least two decades, scientists, policymakers and journals, including Nature, have cited a statistic without determining its validity. The data point in question is that 80% of global biodiversity is under the stewardship of Indigenous Peoples. There is no doubt that Indigenous communities are core to the conservation of biodiversity, but to say that they are stewards of 80% of the world’s genetic, species and ecosystem diversity isn’t supported by evidence, as the authors of a Comment article last week stated (Á. Fernández-Llamazares et al. Nature 633, 32–35; 2024).

No basis for claim that 80% of biodiversity is found in Indigenous territories

A single, unsubstantiated number also does not reflect Indigenous values and world views, the authors add. There are better indicators and statistics on Indigenous communities and biodiversity, says Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, a co-author of the Comment article and an ethnobiologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain, in an accompanying Nature Podcast.

Biodiversity — defined as the variety of life on Earth, including its variation at the level of genes, species and ecosystems — is extremely hard to quantify. Even the simplest statements come with great uncertainty: there is no consensus, for example, on the number of species on the planet1. There are at least 50 ways to value nature, according to researchers working with the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in Bonn, Germany2.

Podcast: The baseless stat that could be harming Indigenous conservation efforts

The authors of the Comment article, three of whom identify as Indigenous, reveal that the 80% statistic seems to have emerged in policy reports, from which it spread into the scientific literature. As of 1 August, the researchers found the 80% claim mentioned in 186 peer-reviewed journal articles. The earliest mention that they found was in a 2002 United Nations document that said that Indigenous Peoples “nurture 80% of the world’s biodiversity on ancestral lands and territories”, without a citation. The number is repeated in an influential 2008 World Bank report.

So why might this number appear in policy documents first? It stems from Indigenous Peoples’ centuries-old encounters with more-powerful interests, the resulting exploitation and mistreatment, their fight for rights, and the international community’s ongoing policy response.

Assessing the values of nature to promote a sustainable future

Worldwide, there are some 467 million Indigenous People across 90 countries. Today, they are among the poorest, most vulnerable and least protected people in their nations. Some international laws and modern research practices pertaining to biodiversity derive from the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity. This agreement has its origins in a movement to create protected areas — ironically, areas often initially created by taking away Indigenous Peoples’ rights to land or expelling them. During the negotiation, representatives of low-income countries and Indigenous Peoples fought to ensure that the agreement included provisions for the equitable sharing of biodiversity’s benefits, such as profits from food or medicines.

By the early 2000s, organizations such as the World Bank were working with Indigenous Peoples’ representatives, and examining the impact and legacy of their own previous lending practices on Indigenous Peoples and creating ways to involve them in their decisions.

The research community also had work to do. When IPBES was established in 2012, it pledged, for the first time, to incorporate Indigenous and local knowledge in its global scientific assessments of biodiversity. Studies are now being co-produced between Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors. A next step needs to be more studies designed and led by Indigenous authors3.

Around the world, the struggle for Indigenous rights has a long way to go. Researchers have a crucial role in supporting communities, which includes being rigorous with data. As Fernández-Llamazarez says in the Nature Podcast, unproven data risk fuelling scepticism on the role of Indigenous communities in biodiversity stewardship.

More News

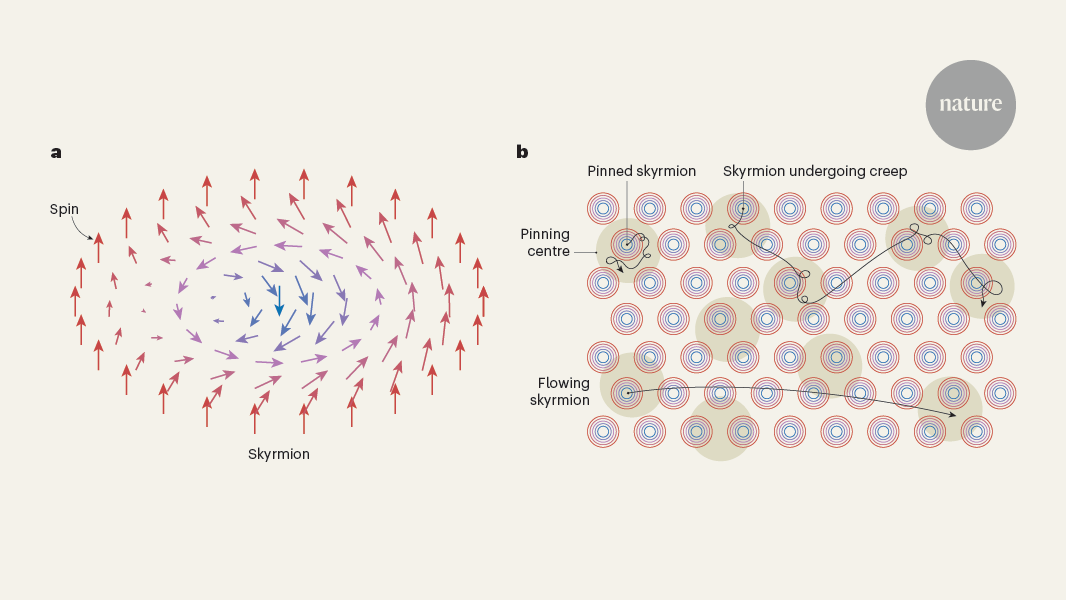

Magnetic whirlpools creep and flow in response to emergent electrodynamics

Rules of river avulsion change downstream – Nature

Three-dimensional wave breaking – Nature