Credit: Illustration by Cathal Duane

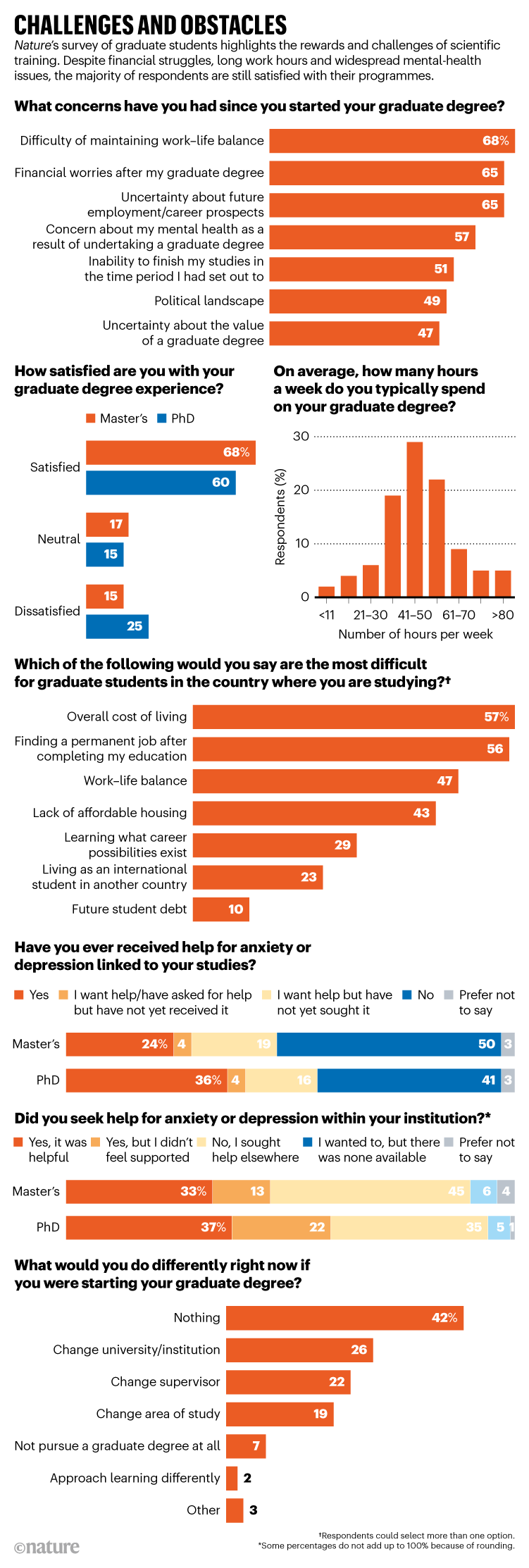

Faced with financial hardships, multiple demands on their time and uncertain career prospects, some graduate students are losing faith in their chosen career path. In Nature’s 2022 global survey of graduate students — its sixth such survey since 2011 and the first to include master’s students — just 62% of respondents say they are satisfied with their current programme, a notable drop from 71% in 2019, the last time we surveyed PhD students. Half of respondents in the current survey say that their satisfaction has declined since starting their programme.

The survey involved 3,253 self-selected respondents around the world (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21277575). Thirty-five per cent of responses came from Europe, 28% from North America, and 24% from Asia. The rest were spread roughly equally between South America, Africa and Australasia. Fifty-six per cent of respondents identified as female, and 42% as male. Master’s students accounted for nearly one-quarter of all responses, a significant showing for a group that has historically been understudied and, arguably, underappreciated.

Through survey answers and free-text comments (see ‘Snapshots of the ups and downs of graduate life’), respondents shared their thoughts on their master’s or PhD programme and their quality of life. The results underscore widespread challenges that, for some, threaten to derail their training, including high stress levels, poor work–life balance and struggles with anxiety or depression (see ‘Challenges and obstacles’).

Survey responses offer an insight into what works in graduate-student training worldwide — and what needs to change, says Katelyn Cooper, a biology-higher-education researcher at Arizona State University in Tempe, who reviewed the results. The decline in rates of satisfaction since 2019 are of particular concern, she says. “We shouldn’t be satisfied with 62%” of respondents being content with their programme, “especially given how long people commit to graduate school”, she says. “We need to do better.”

Institutions, Cooper says, need to take steps to make students more financially secure and better prepared for future careers, and help them to feel supported more effectively during times of stress. “We’re a long way from where we need to be, given how important it is to produce scientists,” she adds. “If this keeps up, we aren’t going to be able to produce enough people who are excited about tackling the world’s most difficult problems.”

Expectations versus reality

Challenges aside, most students feel they are on the right path. Seventy-six per cent of respondents say they are satisfied with their decision to pursue a graduate degree, including 21% who are “extremely satisfied” with their decision. More than half (56%) say that their programme is living up to expectations and 10% say that it is exceeding them. When asked to select from a list of things they like most about their programme, the majority of students note the intellectual challenge (63%) and working with interesting and bright people (59%).

Still, more than one-third (35%) of respondents say that their programme doesn’t meet their original expectations. For many, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting shutdowns and disruptions have contributed to souring attitudes. Sixty-five per cent of respondents say that the pandemic has negatively impacted the quality of their programme. The most commonly cited reasons for this are a lack of social support and peer interaction; a lack of networking opportunities and in-person events; and disruption of coursework and research. “COVID interrupted a lot of social aspects of grad school that are very protective of mental health,” Cooper says.

Collection: Career resources for PhD students

The survey results underscore the enormous effort that goes into pursuing an advanced degree. For most, it’s a full-time endeavour. Seventy per cent of respondents say they spend more than 40 hours a week on their programme, and nearly half agree with the statement “There is a long-hours culture at my university, including sometimes working through the night.” Forty-one per cent say they are very concerned about the difficulty of maintaining a decent work–life balance. In the comment section of the survey, a PhD student in Italy says that he never really has time off and that his adviser calls him on weekends. Just over one-third (34%) of respondents agreed that their university supports a good work–life balance.

The many tasks required of graduate students can be a major source of stress, says Cooper, who co-authored a 2021 study that looked at the impacts of research, teaching and other duties on mental health (L. E. Gin et al. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 20, ar41; 2021). It found that failed experiments, negative feedback from supervisors and social isolation can deepen depression. Even though teaching classes can add greatly to a graduate student’s workload, Cooper and her co-authors found that the sense of accomplishment that comes from instructing others can actually be a buffer against mental-health problems. “Teaching seems to be one of the only opportunities for consistent positive reinforcement in graduate school,” she says.

One out of five students reports having care duties for children or adults, an extra responsibility that can greatly add to the emotional and financial strain of graduate school. In such situations, support from an institution or funding body can make a huge difference, says Colleen Limegrover, who hopes to complete her PhD programme by the end of the year at the University of Cambridge, UK. Limegrover, who is supported by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship, was able to go on paid maternity leave after she had a child in 2020, a luxury that is unavailable to many other graduate students.

She was also able to afford childcare outside the home. “My livelihood and mental health have been great,” she says. “That’s because of the support of my funding body.” (Editor’s note: We’ll take a closer look at salaries and financial support in next week’s story.) She knows other parents who have to manage their PhDs without the benefit of such childcare. “That really impacts the way you see your programme,” she says.

A spotlight on mental health

Mental health remains a crucial issue in today’s graduate programmes. One-third of respondents report that they have already received help for anxiety or depression caused by their graduate-school work. Another 21% say they want help but have yet to receive it. Less than one-third (29%) of respondents agree that “mental-health and well-being services at my university are tailored and appropriate to the needs of graduate students”. “There’s still a stigma surrounding mental health in science,” Cooper says. “The first step is feeling comfortable seeking help, but you also have to be able to find it and afford it.”

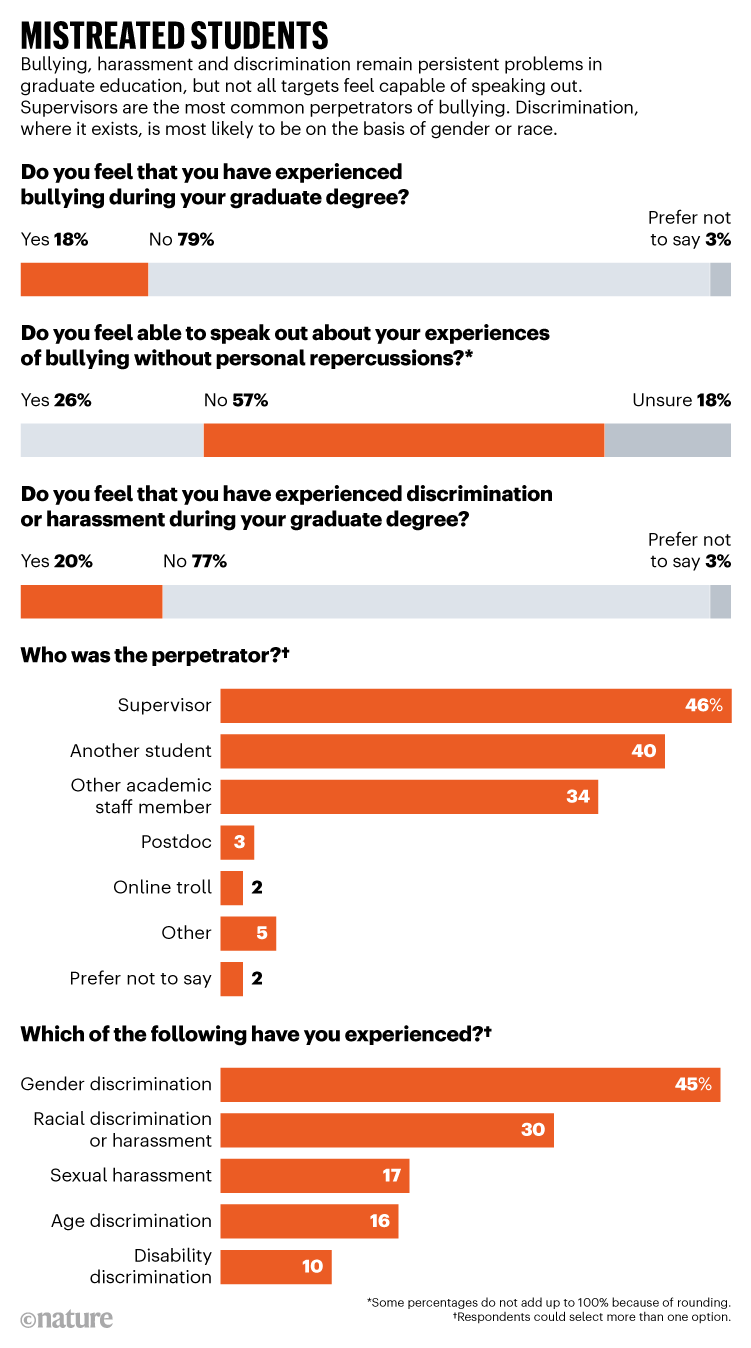

Survey respondents confirm that bullying is an ongoing problem in academia (see ‘Mistreated students’). Eighteen per cent of respondents say that they have personally experienced bullying in their programme, down slightly from 21% in the 2019 survey. Of those who say they have experienced bullying, just over one-quarter (26%) say that they felt free to speak out about their situation without fear of personal or professional repercussions. “When I started my PhD, I was bullied by my supervisor for a year,” writes a bioscience student in the United Kingdom in the comment section of the survey. “Colleagues around me who saw what was happening wrote it off as being the culture in academia. I wish I’d known it didn’t have to be [that way] and that I could change my supervisory team.”

Supervisors: good and otherwise

The relationship between graduate students and their supervisors is a crucial component of any programme. When asked what they would do differently if they could start again, more than one-fifth (22%) of respondents say they would change their supervisor and more than one-quarter (26%) say they would change their institution. A PhD student in the United States says he wished he’d known that “a bad adviser will ruin your education experience and prospects”. A PhD student in Australia comments: “Supervisor/lab group is everything. Topic/field doesn’t matter. The environment you work in is most important to help you get through the graduate degree.”

PhDs: the tortuous truth

Students’ relationships with their supervisors was a recurring theme throughout the survey. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of respondents say that they are satisfied overall with their relationship with their adviser, and 72% of respondents are satisfied with their degree of independence.

Xiangkun Cao, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, responded to the survey shortly after earning his PhD in engineering at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He says that his supervisor was key to his ultimate success. At the start of the programme, he struggled with some of the questions that countless graduate students before him had faced. Had he made the right choice? And if it was the right choice, why did he feel so miserable?

Xiangkun Cao did his PhD at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.Credit: Xu Liu

Cao, who goes by the name Elvis, didn’t think he fitted in with his research group. He also wasn’t sure where his career was headed, and he didn’t feel comfortable in a small New York town far from China, his home nation. “I had lost all of my confidence, and I couldn’t sleep,” he says. “When I called home, I pretended everything was fine. But I was suffering.”

Instead of quitting, Cao found his place and his calling by switching to a different group at Cornell. He started studying carbon capture, potential planet-saving technologies that also saved his love of graduate school. Cao’s PhD work on artificial photosynthesis landed him on the prestigious Forbes magazine ‘30 Under 30’ list — of people whom magazine editors consider leaders in their field — in 2019.

Cao says that he wasn’t aware of any mental-health services during his depression in the early days of his programme in 2016. But he did find a different sort of help. He shared his troubles with a graduate ‘field assistant’, an adviser at Cornell who works as a liaison between students and faculty members. That assistant connected him with the director of graduate studies, who helped him to switch labs and start again with a new supervisor. Cao discussed this process and his experience of mental-health challenges in a commentary earlier this year (Z. F. Murguía Burton and X. E. Cao Nature Rev. Mater. 7, 421–423; 2022).

No regret

Joanna Nowacka, a fourth-year PhD student who is close to wrapping up her programme at Miltenyi Biotec, a biotechnology company in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, doesn’t regret her decision to pursue a graduate degree. “I’m perfectly happy and satisfied with my PhD,” she says. But, unlike the great majority of respondents, she’s training at a company rather than a university. That, she says, has a lot to do with her satisfaction.

Like many other students who are nearing the end of their PhDs, she’s currently working on a thesis, but, by contrast, she does not have to worry much about publications. “I don’t have as much pressure as my colleagues in academia,” she says. “The pressure in academia can be very high — the pressure to publish, the pressure to get results that are publishable.” In her position, she can focus more on her project (the details of which, she says, are proprietary).

Struggles and regrets are part of graduate-student life, but more than 40% of respondents say that they wouldn’t change anything about their programme. That includes Cao. He once feared that pursuing a PhD was the biggest mistake of his life, but, for him, it turned out to be a long, challenging step in the right direction. “I’ve been very fortunate,” he says.

More News

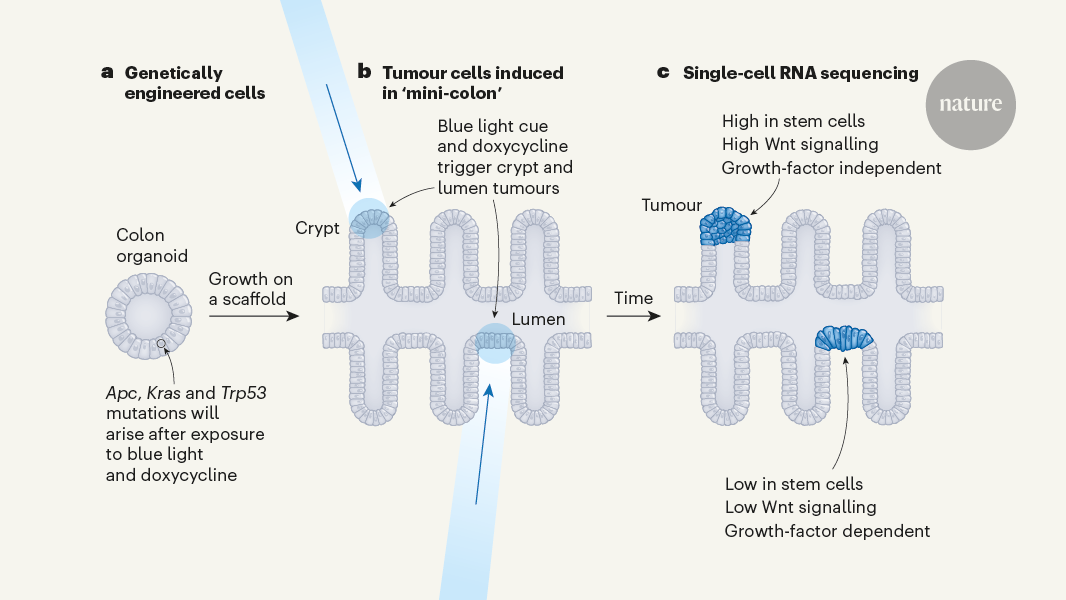

Bioengineered ‘mini-colons’ shed light on cancer progression

Robust optical clocks promise stable timing in a portable package

Marsupial genomes reveal how a skin membrane for gliding evolved