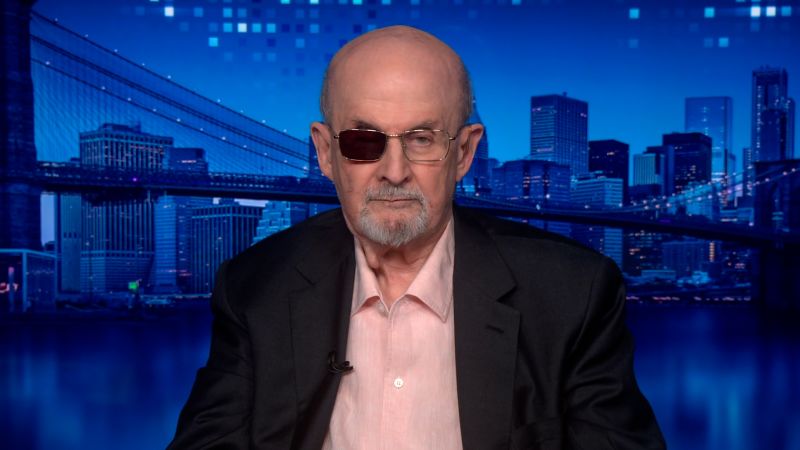

Imperial College London is among the institutions that received the largest funding from the EU’s previous research scheme, Horizon 2020.Credit: iStock Editorial/Getty

The UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy is quietly returning £1.6 billion (US$1.9 billion) in funding to the Treasury that had been earmarked for research collaborations with the European Union in its 2022–23 budget. But the government swears that the money is not lost to UK science.

The government had set aside £2.35 billion to fund the United Kingdom’s contributions to the Horizon Europe research-funding scheme and Euratom nuclear-energy organization, which funds the ITER fusion research project in France. But because the country’s participation in those programmes has still not been confirmed, part of that money went unspent and was surrendered back to the Treasury. The clawback was revealed on page 300 of a technical accounting document.

The scientific community swiftly condemned what appeared to be the loss of promised funding for research and development (R&D), after repeated assurances by the government that UK researchers would not lose out if the country failed to reach an agreement on the Horizon Europe programme.

Community concerns

The London-based Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE) first highlighted the issue on 21 February. “The government has repeatedly stated that R&D budgets would be protected and that the money allocated for association to Horizon Europe would be spent on R&D,” said Sarah Main, CaSE’s executive director, in a statement. “The government’s reversal of this position with today’s withdrawal of £1.6bn for R&D undermines the Prime Minister’s assertions about the importance of science and innovation to the UK’s future and the creation, only this month, of a new department to pursue this agenda.”

The leaders of several scientific organizations, including the UK Royal Society and the Institute of Physics in London, also voiced their concerns over the apparent loss.

But a government spokesperson told Nature that the money was not lost, and that the commitment to increasing public R&D investment to £20 billion per year by 2024–25 remains in place. “Funding remains available to finalize association with EU programmes, but we have been clear that we will only pay for the periods of association. In the event we do not associate, UK researchers and businesses will receive at least as much money as they would have done from Horizon over the Spending Review period,” he says.

Even if the negotiations had been successful, it is unlikely that UK researchers would have received all of those £2.35 billion from Horizon Europe last year. The sum was an up-front payment to join, and the returns from it would have been spread over several years as researchers won grants.

Brexit guarantee

After Brexit went into effect, Horizon Europe continued to accept grant applications from UK-based researchers, with the understanding that EU funding was contingent on the successful negotiation of associated-country status. The Horizon Europe guarantee — under which the UK government provides funding to researchers whose applications have been approved by Horizon Europe, but who have been unable to receive funding while the United Kingdom is negotiating — is still in place until at least the end of March.

To date, the government has provided £750 million via UKRI through the guarantee, the spokesperson says, and £684 million of direct funding to UK science, fusion and Earth observation. The government will soon publish detailed plans for alternative programmes, which will be implemented if needed, he adds.

James Wilsdon, who studies science policy at University College London, says the underspend is partly due to the fact that fewer UK academics are applying to Horizon Europe because of the uncertainty surrounding the United Kingdom’s relationship to the EU. As a result, spending on the UK guarantee and related measures ended up being less than the amount the government had estimated it would have had to pay into Horizon Europe if it had joined.

Downward spiral

“Even with the guarantee in place, the volume of UK applications continues to drop,” Wilsdon says. “It’s a vicious downward spiral, where uncertainty breeds declining engagement, which then further decreases the theoretical drawdown of this money through the UK guarantee or ultimately through reconnection through an association agreement.”

Even if the money is later made available for research, either through association with Horizon Europe or through the yet-to-be-announced alternative, the failure to clearly communicate this reinforces the worst fears of the research community, says Wilsdon.

Kieron Flanagan, who studies science and technology policy at the University of Manchester, UK, says the confusion will do little to build confidence in the government’s plans for science. “It looks absolutely awful and is a terrible own goal for a government attempting to put science and technology at the centre of its strategy for growth,” he says.

More News

DNA from ancient graves reveals the culture of a mysterious nomadic people

Rat neurons repair mouse brains — and restore sense of smell

Transient loss of Polycomb components induces an epigenetic cancer fate – Nature