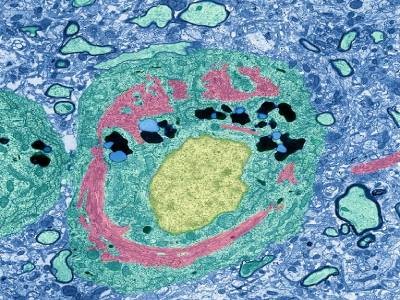

A scan (artificially coloured) of the brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease.Credit: K H Fung/Science Photo Library

An experimental drug can slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease in those who start it when the disease is still in its early stages. The drug, a monoclonal antibody called donanemab, does not improve symptoms. But among people who started taking it at the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s, 47% had no disease progression on some measures after one year, compared to 29% who took placebo.

The drug does not provide as much benefit to people at later stages of the disease or those with a common genetic mutation that raises the risk of Alzheimer’s.

“This decade is already proving to be the decade of Alzheimer’s,” said Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer Maria Carrillo at a press conference at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) in Amsterdam. “It’s important to now double down and not slow down.”

Donanemab’s manufacturer Eli Lilly, based in Indianapolis, Indiana, presented the results of the 1,736-person trial today at AAIC and published them1 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The company released partial results in May, but those results left researchers with questions about the drug’s safety and efficacy in certain patient populations.

Sticky target

Like many other of the newest generation of Alzheimer’s drugs, donanemab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the sticky, neuron-damaging protein amyloid in the brains of people with dementia. Both donanemab and the similar drugs lecanemab and aducanumab can cause a condition called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which can cause potentially fatal brain bleeding and seizures. Around one-quarter of the participants in Lilly’s phase developed ARIA, and three died of the condition. The rate of ARIA was even higher among study participants who carry a gene called APOE4, which raises the risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

This is how an Alzheimer’s gene ravages the brain

Participants carrying APOE4 benefitted less from donanemab than participants who do not have the variant, Lilly’s new data showed. The full results also revealed that the drug works far better in patients who start it when they have low levels of another brain protein called tau. Tau is known to increase throughout Alzheimer’s progression, although its role in the disease is still poorly understood.

People with low or moderate levels of tau who took donanemab declined 35% more slowly over the course of 76 weeks than those who took placebo. But those with high tau levels continued to decline at the same rate whether they took donanemab or a placebo. In the press conference, Mark Mintun, vice president of neuroscience research and development at Lilly, said that while it is important to develop better tests for tau, he doesn’t think it will be mandatory for physicians to evaluate a patient’s tau levels before deciding to give the drug.

Slowing the decline

In people who started taking the drug while in the earliest stage of cognitive impairment, donanemab slowed the rate of cognitive decline by as much as 60%. The drug also cleared around 90% of the total amyloid from the brain. Once people had minimal amyloid levels, the investigators switched them to placebo. In the year after the switch, those who had taken donanemab continued to decline at a slower rate than those who had initially received a placebo.

And even after stopping the drug, those who had taken it continued to decline at a slower rate over the course of one year than those who had initially received placebo.

“It a well conducted trial with overall good news,” psychiatrist Gill Livingston of University College London said in statement to the Science Media Centre. “It is clear that in the short term these drugs help a little in the populations tested.” But she points out that it is still unclear whether the drug will work for longer than 18 months, and notes that while it can help people in the early stages of disease who are physically well, “there is still a lot of work to do to know what it means for most people with Alzheimer’s dementia.”

In a press conference at AAIC, Lilly’s senior medical director John Sims said that the company has filed for FDA approval and expects to hear back by the end of this year.

Sims and Mintun declined to comment on how much donanemab would cost if approved, but lecanumab and aducanumab have been priced at over US $26,000 per year.

More News

Beware of graphene’s huge and hidden environmental costs

Countering extreme wildfires with prescribed burning can be counterproductive

Hacking the immune system could slow ageing — here’s how