Most maternal deaths are due to preventable causes, say researchers.Credit: Paula Bronstein/Getty

Countries have fallen behind on their goal to slash the rate of maternal deaths this decade, according to an analysis by various United Nations agencies published this week.

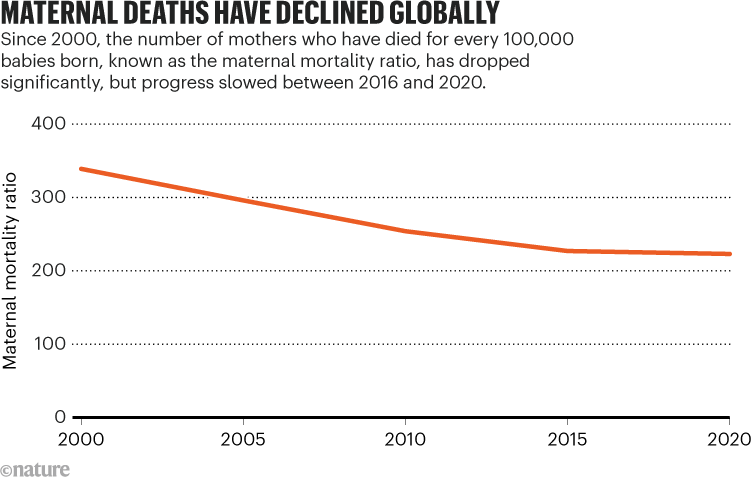

For every 100,000 babies born in 2020, 223 mothers lost their lives owing to pregnancy or childbirth — a 33% drop in the maternal mortality ratio since 2000. But that number is still a long way from the target of 70 deaths per 100,000 births that countries committed to reaching by 2030 as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Mary Nell Wegner, executive director of the Brindle Foundation, a non-profit that supports care from pregnancy to early childhood and is based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, says she felt that when the goal was set in 2016, it was aspirational and possible. “It no longer feels within reach,” she says.

Progress stalls

The latest analysis tallies estimated maternal deaths in 185 countries and regions between 2000 and 2020.

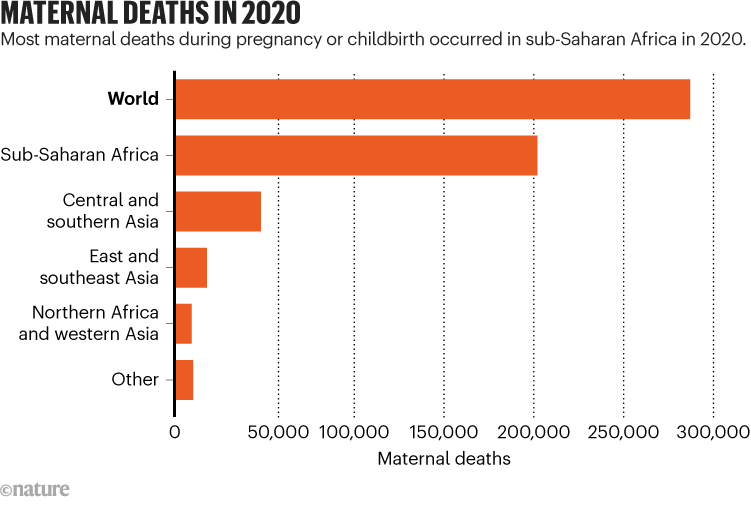

It shows that some progress has been achieved. For instance, roughly 287,000 people lost their lives owing to pregnancy in 2020 — a significant drop from the 446,000 who died in 2000. Most countries and regions have had drops in their maternal mortality ratio during those 20 years.

But progress has stalled since the target was set. Between 2000 and 2015, the average annual drop in the global maternal mortality ratio was just under 3%. But there has been almost no further reduction since then (see ‘Maternal deaths have decline globally’). “It hasn’t moved,” said Jenny Cresswell, an epidemiologist at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, and co-author of the report, at a press briefing on 21 February. For the world to meet its global targets by 2030, the ratio would need to decline by 12% every year, said Cresswell. “This represents a really immense challenge.”

Eight nations in particular, including Cyprus, Greece and the United States, have seen increases in their maternal mortality ratio since 2000. “It is surprising that countries like the US are going so rapidly in the wrong direction,” says Wegner.

Data from 2020 also reveal widespread geographic discrepancies in deaths. Some 70% of maternal deaths that year occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (see ‘Maternal deaths in 2020’). In Chad, Nigeria and South Sudan, where the situation is most severe, at least one woman died for every 100 babies born .

A separate study on data from India shows that inequities also exist within countries — more than 60% of the 23,800 Indian women who died owing to pregnancy in 2020 lived in poorer states1. The risk of death was highest in rural and tribal areas in the north of the country.

Preventable deaths

There are many reasons mothers die during pregnancy or childbirth, ranging from heavy bleeding after childbirth to pre-eclampsia and complications from unsafe abortions or infections. The level and quality of care mothers receive, as well as their income, race and ethnicity also contribute to their risk of death.

“Nearly all of these maternal deaths are due to preventable causes, and this is something which we are very concerned about,” said Cresswell.

Sarita Sitaula, a consultant gynaecologist at Siddhi Memorial Women and Children Hospital in Kathmandu, says that in Nepal, pregnant people often don’t go to regular health check-ups and wait too long before seeking medical assistance because they lack access to health insurance. Roads in rural areas are also poorly built and far from hospitals. When they do get to a health centre, they cannot get the care they need, she says.

Wegner recognizes that as countries get closer to the global target, it gets harder to make clear progress. But many factors have exacerbated the problem in recent years, including conflicts, mass migration and climate change. The global stagnation is “both inexcusable and stunning”, she says.

Wegner also worries that the COVID-19 pandemic has widened disparities since 2020 and made it more difficult to gather trustworthy data because of the strain on health systems. “I desperately hope that I am wrong,” she says.

More News

Judge dismisses superconductivity physicist’s lawsuit against university

Future of Humanity Institute shuts: what’s next for ‘deep future’ research?

Star Formation Shut Down by Multiphase Gas Outflow in a Galaxy at a Redshift of 2.45 – Nature