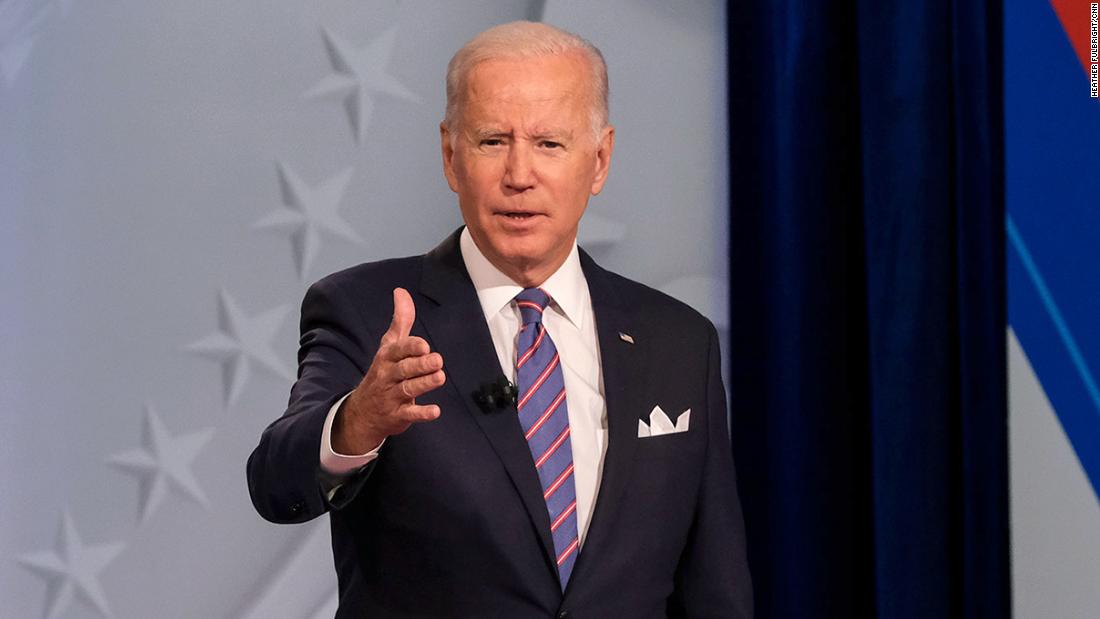

“A tax cut for middle-class people,” Biden told a CNN town hall on Thursday. And because it’s fully available to households with little or no income, the President boasted in Pennsylvania a day earlier, the expanded credit has cut child poverty in the US by 50%.

Advocates cite multiple reasons for the expanded credit’s underwhelming political footprint. They include its link to the pandemic that voters want to leave behind and an intra-party debate on Capitol Hill focused more on the legislation’s price tag than its benefits.

“We’ve done almost nothing to champion this,” complained Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado, a leading Democratic proponent. Parents who have benefited, he added, “are profoundly grateful. They don’t know who to be grateful to.”

“For many voters, simply getting more money back from the government isn’t necessarily a cure-all for the challenges they see around them,” explained Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson. Meantime, she added, debate over Biden’s plan “is so confusing. All people know is, it’s infighting in Congress and it’s a lot of money.”

A survey Anderson helped prepare for the advocacy group Marshall Plan for Moms showed the Child Tax Credit enjoying majority support. But other priorities including paid family leave and more affordable health care coverage — both of which are also getting shrunk in the Democratic compromise – were considerably more popular.

That’s not due to limited access. The credit is available in full for households earning up to $150,000, which covers the vast majority of American families. It gradually phases down beyond that level.

Some insist that near-universal availability, rather than broadening the expanded credit’s appeal, actually limits it. Democratic data analyst David Shor argues a narrower program may be more politically sustainable.

“In general, voters like to receive benefits themselves,” Shor and a colleague wrote recently on the SlowBoring website. “But when thinking about benefits for other people, they often prefer that social spending be targeted to those who need it most.”

Biden supports embedding the expanded credit, which costs more than $100 billion annually, permanently into law. To preserve cash for other priorities, however, an initial version of the pending legislation extended it for only four years.

As resistance from moderates shrinks the price tag from $3.5 trillion to around $2 trillion, negotiators have since moved toward a one-year extension. In either case, Democrats hope public support would prevent even a Republican Congress from letting it expire.

“People tend to be loss averse,” reasoned Chuck Marr of the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “So they might not give someone as much credit for the gain, but when someone else tries to take it away, then the political benefit would be more apparent.”

Republicans in 2017, for example, couldn’t muster the votes to repeal Obamacare despite its up-and-down political past. Yet there’s a crucial difference: an expiration date would let hostile lawmakers kill the expanded credit without taking any action at all.

As a result, advocates are quietly negotiating a fallback.

The Child Tax Credit that existed before Biden increased it as high as $3,600 let the lowest earning families — those without income tax liability to offset with a credit — claim no more than $1,400 of the $2,000 maximum. Now, Bennet and others are pressing to make the $2,000 maximum for that previous version of the credit fully and permanently available to even those lowest earners.

If they succeed, full “refundability” would endure even if the expanded Biden credit expires. Simply doing that, by Marr’s calculation, would reduce child poverty from its pre-Biden level by 20%.

More News

Pope Issues Apology After Reports That He Used Offensive Slang Word

Calls Mount to Let Ukraine Strike Russia With Western Weapons

Trump’s Trial Has Entered Its Final Stages. Here’s What Comes Next.