A fossilized tooth unearthed in a cave in northern Laos might have belonged to a young Denisovan girl that died between 164,000 and 131,000 years ago. If confirmed, it would be the first fossil evidence that Denisovans — an extinct hominin species that co-existed with Neanderthals and modern humans — lived in southeast Asia.

The molar, described in Nature Communications on 17 May1, is only the second Denisovan fossil to be found outside Siberia. Its presence in Laos supports the idea that the species had a much broader geographic range than the fossil record previously indicated.

“We’ve always assumed that Denisovans were in this part of the world, but we’ve never had the physical evidence,” says study co-author Laura Shackelford, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “This is one little piece of evidence that they were really there.”

Expanded range

Denisovans were first identified in 2010, when scientists sequenced DNA from a fingertip bone found in Denisova cave in Siberia, and showed that it belonged to a previously unknown species of ancient human2. Subsequent genetic studies3,4 have revealed that millions of people from Asia, Oceania and the Pacific Islands carry traces of Denisovan DNA.

This suggests that the species ranged far beyond Siberia — but the fossil evidence has been sparse. The entire fossil record for Denisovans so far boils down to a handful of teeth, bone shards and a jawbone found in Tibet. Aside from the latter, every specimen (including a piece of bone that belonged to a half-Denisovan girl whose mother was a Neanderthal) has come from Denisova cave.

That’s partially because fossils have a better chance of surviving in cold, dry conditions than in warm, humid ones. But in 2018, Shackelford and her colleagues were looking for potential dig sites in northern Laos when they came across a cave “just filled with teeth”. These belonged to a mixture of species, including giant tapirs, deer, pigs and ancient relatives of modern elephants. The collection was probably amassed by porcupines collecting bones to sharpen their teeth and extract nutrients, says Shackelford. Among the first batch of fossils to come out of the cave was a small, underdeveloped hominin tooth.

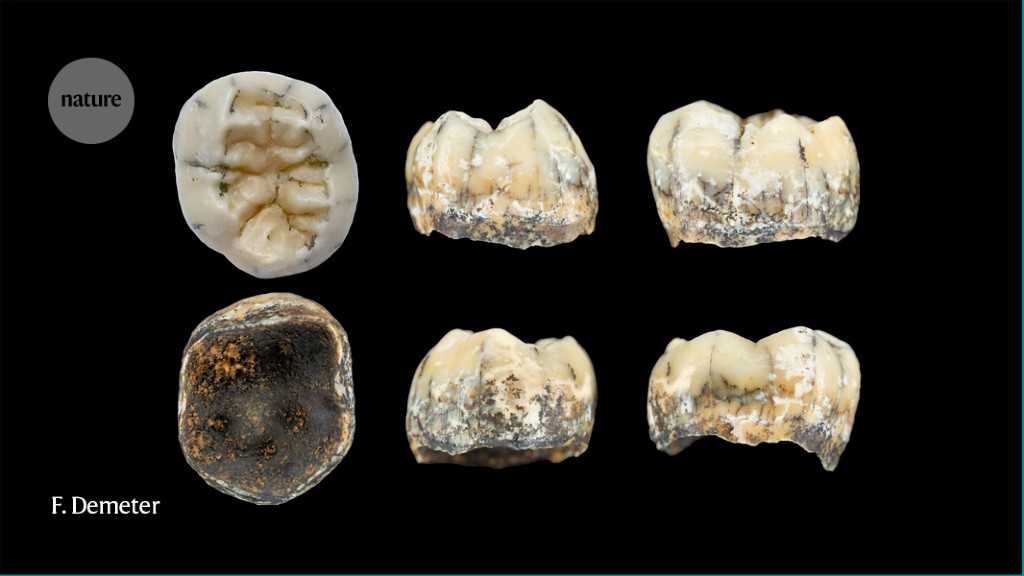

Dating of the cave’s rock and animal teeth revealed that the tooth pre-dated the arrival of modern humans in the area. “It was just a huge surprise,” says Shackelford, who says the team wasn’t expecting to find ancient-human remains. At first, the researchers thought the tooth might belong to Homo erectus — an ancient-human species that lived in Asia between around 2 million and 100,000 years ago. But the molar is “too complex” to belong to H. erectus, the researchers say, and although it shares some characteristics with Neanderthal teeth, it is also “large, and kind of weird”, says Bence Viola, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Toronto in Canada.

The molar has the greatest resemblance to teeth found in the Denisovan jawbone from Tibet. “Denisovans have absolutely gigantic teeth,” Viola says. “So it seems like a good assumption that this is likely a Denisovan.”

The tooth’s roots are not fully developed, so it probably belonged to a child, the researchers say. They also found that it lacked certain peptides in its enamel that are associated with the Y chromosome — a possible indication that its owner was female.

Right place, right time

Reconstructing the identity of a person whose bones have been degraded by thousands of years of tropical conditions is challenging, says Katerina Douka, an archaeological scientist at the University of Vienna. Without more fossils or DNA analysis, “the reality is that we cannot know whether this single and badly preserved molar belonged to a Denisovan”, she says.

But Viola says that the molar is in the “right place and right time” to belong to a Denisovan. If this were confirmed, it would reveal that the species was able to adapt to different environmental conditions. At the time the tooth’s owner died, more than 131,000 years ago, the area would have been lightly wooded and temperate — completely different from the frigid temperatures faced by Denisovans in Siberia and Tibet. The ability to live in a wide range of climates would set the Denisovans apart from Neanderthals — whose bodies were adapted for colder places — and make them more similar to our own species.

Even with the uncertainty, the discovery is likely to encourage other researchers to look for ancient-human fossils in southeast Asia, says Viola.

“When we started looking in Laos, everyone thought we were crazy,” says Shackelford. “But if we can find things like this tooth — which we weren’t even anticipating — then there are probably more hominin fossils to be found.”

More News

Author Correction: Bitter taste receptor activation by cholesterol and an intracellular tastant – Nature

Audio long read: How does ChatGPT ‘think’? Psychology and neuroscience crack open AI large language models

Ozempic keeps wowing: trial data show benefits for kidney disease