Scientists often struggle to explain their research in lay terms — whether to funding agencies and tenure and promotion committees, or to friends and family.

I study tissue regeneration in worm models of injury and tissue repair. I also study how health-care interruptions due to the pandemic have affected people with cancer. Like all researchers, I publish my findings in peer-reviewed journals. But those are for other researchers. As Steven Pinker, a cognitive scientist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, wrote in a 2014 essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education, academic writing is often “bloated, obscure, clumsy and unpleasant to read”. Not to mention that many good articles are hidden behind paywalls.

So, to make my research more accessible, I decided to take advantage of a resource that much of the world already uses: YouTube.

After Google, YouTube ranks as the second-most-visited website worldwide, with more than 22 billion monthly visits. It’s my go-to platform for learning data-science techniques. Hardly a week goes by without me typing ‘How to’ in YouTube’s search box, and I’m not alone: many people use the site to find solutions to their problems or questions.

In September, I launched the Zero to Data Science channel on YouTube with the aim of sharing research and data-science content in simple and relatable language. We created our first video to share findings on medication compliance in people with heart conditions. The video used text animations, video clips and still images. My dad, who is not a scientist, served as a sounding board: his comments emphasized that making research findings accessible to the public is harder than it looks. “The scenes are shifting too quickly,” he said. “One has to be a speed reader to read through everything before the next scene starts.”

Since its launch, our channel has accrued nearly 27,000 impressions (a measure of potential reach), 200 hours of watch time and 4,600 views of our videos. Sharing video teasers on Twitter with links to the full videos on YouTube generated another 28,400 impressions. To put those numbers into perspective, all my research papers together have received about as many reads in ten years (according to ResearchGate) as the number of impressions that our channel received in two months.

I have received personal messages from strangers and students saying that the videos inspired them to pursue a data-science degree, learn a new technique, get started with data wrangling or understand research results.

As research funders place greater emphasis on public engagement to ensure that public money is well spent, videos provide a good way to get the message across. After all, what good is research that isn’t shared and understood?

Animation toolbox

For many readers, the biggest hurdle to communicating research using animations is psychological: you think you cannot draw, so you don’t incorporate drawing in your work. But if you can manage a stick figure, you can draw. We are limited only by our creativity. Granted, drawing, like any other skill, takes time to master. But many scientists are already familiar with the basic tools, especially Adobe Illustrator, a design programme based on vector graphics that is used to create composite images for publication. My toolbox (see ‘Video animation toolbox’) also includes Adobe Fresco, which offers a range of raster and vector brushes for producing watercolour-style images. I’ve compiled Adobe Fresco tutorials in a playlist on our channel.

Beyond the images themselves, you can add personality to your videos with voiceovers. People ‘listen’ to YouTube videos while they go about their day. So not only should your video look appealing, but it should sound dynamic, too. I try to imagine myself getting into character and believing in what I am saying. Voiceover scripts make the performance easier. In one video, I portray a fictional childhood-cancer survivor named Chrissy; in another, I voice a frog, football, cat and girl, to illustrate data-science concepts and collaborative learning.

If you need help, find local animators or artists who have a shared interest in science communication. Your university’s art or science-communication department is a good place to start. At University College London, where I work, the UCL Culture team promotes engagement activities focusing on art. Combining arts with science is more common than you might think: a poll conducted by Nature last year revealed that about 40% of survey respondents have collaborated with artists and will continue to do so moving forward.

Collaborative videos can both entertain and inform, and can even ease viewers into new fields of study.

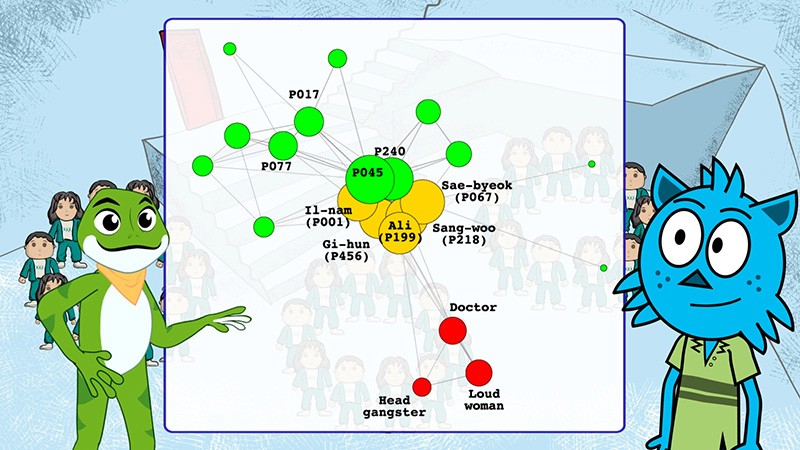

For instance, a friend in the insurance sector told me that they wanted to teach their staff about machine learning to manage claims processing. We created a five-minute tutorial and released it alongside a mock dataset and R-programming code for enthusiasts to practise on. Businesses frequently use trending topics in e-commerce and popular culture to extend their reach, and this video was no different: it was one of a series of five involving the popular Netflix television series Squid Game. Our most recent tutorial explains Cox regression analysis as a way to predict who will win a Squid Game challenge in which players must walk across tiles of tempered or untreated glass.

Using videos to communicate research is fun, entertaining, challenging and rewarding. Videos create a bridge between researchers and the public by making research accessible to anyone with Internet access. When a friend told me that her six-year-old child loves watching the animated character in our Chrissy video, and even remembers and imitates what she said, I knew my efforts were paying off. This seal of approval from a young child has given me confidence in using videos to inspire the next generation of scientists.

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged.

More News

Author Correction: Bitter taste receptor activation by cholesterol and an intracellular tastant – Nature

Audio long read: How does ChatGPT ‘think’? Psychology and neuroscience crack open AI large language models

Ozempic keeps wowing: trial data show benefits for kidney disease