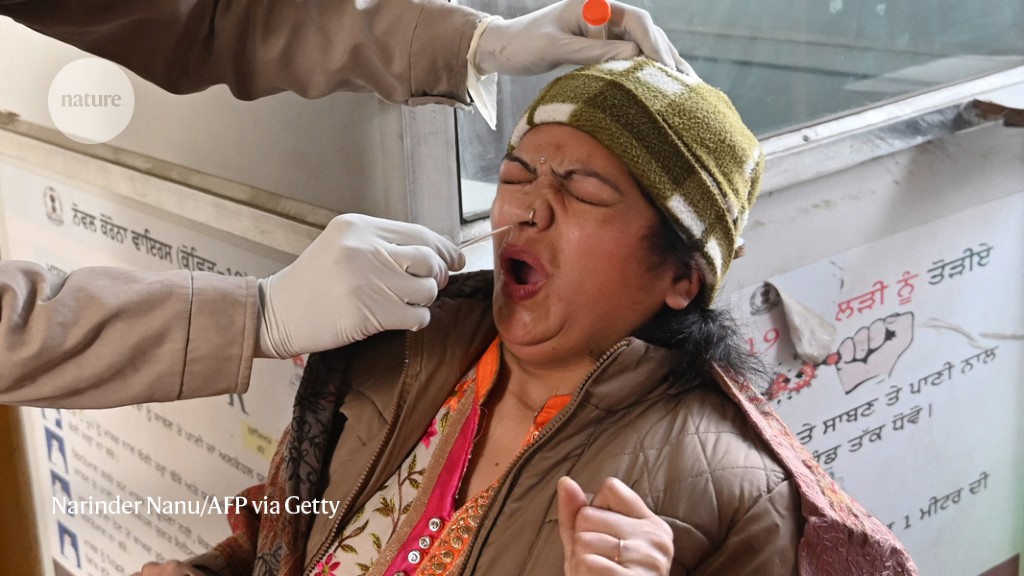

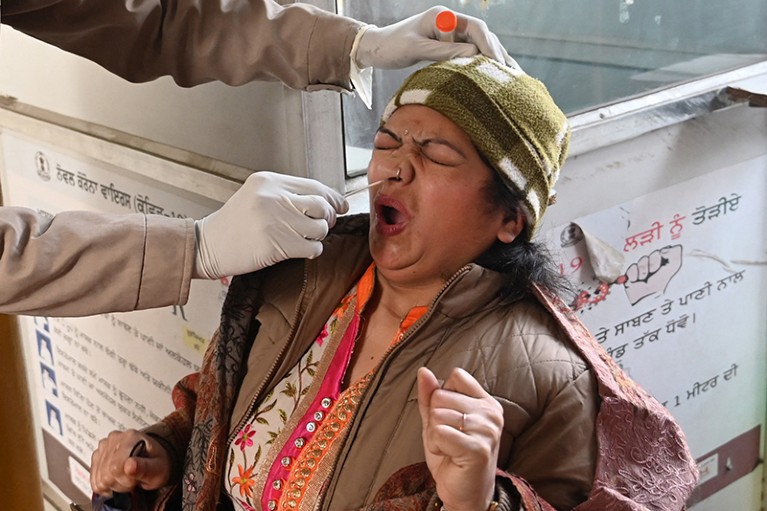

A woman is tested for COVID-19 in India, which has recorded a surge of infections driven by a SARS-CoV-2 variant called XBB.1.16.Credit: Narinder Nanu/AFP via Getty

Whether you call it a surge, a spike, a wave or perhaps just a wavelet, there are signs of a rise in SARS-CoV-2 infections — again. A growing proportion of tests in some countries are coming back positive, and new variants, most notably a lineage called XBB.1.16, are pushing aside older strains, fuelling some of the uptick in cases.

Welcome to the new normal: the ‘wavelet’ era. Scientists say that explosive, hospital-filling COVID-19 waves are unlikely to return. Instead, countries are starting to see frequent, less deadly waves, characterized by relatively high levels of mostly mild infections and sparked by the relentless churn of new variants.

Are repeat COVID infections dangerous? What the science says

Wavelets don’t always create a dramatic spike in hospitalizations and deaths; their effects on health vary between countries. But the relentless series of wavelets looks very different from the slower, annual circulation patterns of influenza and cold-causing coronaviruses, and it seems increasingly unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 will settle into a flu-like rhythm anytime soon, say scientists.

“We haven’t slowed down in the last year, and I don’t see what factors would cause it do so at this point,” says Trevor Bedford, an evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington. “It will be a continually circulating respiratory disease. It may be less seasonal than things we’re used to.”

Victorious variant

In March, scientists in India started seeing signs that a new SARS-CoV-2 variant was causing a rise in infections. The XBB.1.16 lineage has displaced others that drove case surges in India several months ago, says Rajesh Karyakarte, a microbiologist at Byramjee Jeejeebhoy Government Medical College in Pune, India. “We see that it has almost replaced all other variants in India, and we think the same thing will be followed everywhere.”

In a study1 posted to the medRxiv.org preprint server, Karyakarte and his colleagues analysed more than 300 cases, from last December to early this month, and found that XBB.1.16 infections tend to cause mild symptoms similar to those from earlier Omicron variants, with few hospitalizations and deaths. “We didn’t see much,” Karyakarte says. The study has not yet been peer reviewed.

How your first brush with COVID warps your immunity

The World Health Organization declared XBB.1.16 a ‘variant of interest’ on 17 April. But whether it or another new variant will cause a spike in infections in a particular country will probably depend on the size and timing of the country’s earlier waves, says Tom Wenseleers, an evolutionary biologist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium.

He estimates that XBB.1.16 is spreading fairly rapidly in the United States, where it is now estimated to make up more than 11% of cases. In Europe, the variant is less prevalent and is spreading more slowly. This could be due to Europe’s relatively large and recent spike in infections caused by a closely related variant, XBB.1.5, which struck earlier in the United States.

Wavelet, surge, repeat

Some countries are experiencing surges of infections three or four times each year, driven largely by the breakneck pace at which the virus continues to change, says Bedford. Currently, SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein, in which most immunity-evading mutations occur, is evolving at twice the rate of a similar protein in seasonal influenza and about ten times as quickly as those of cold-causing ‘seasonal’ coronaviruses.

Influenza and common-cold coronaviruses cause seasonal epidemics in part because of favourable transmission conditions, such as people spending more time indoors during winter. The combination of rapid mutation and short-lived human immunity is probably preventing SARS-CoV-2 from settling into seasonal patterns of circulation, says Wenseleers.

The stubbornly high frequency of SARS-CoV-2 surges translates to large numbers of infections. Data from the now-defunct UK survey of SARS-CoV-2 prevalence suggested that the country experienced as many infections as it has residents in the last year, which equates to a 100% annual ‘attack rate’, says Bedford. In the future, “we can still imagine 50% attack rates every year, half the population getting infected”, compared with around 20% with influenza.

Emulating influenza

There is little doubt, however, that SARS-CoV-2’s continuing ebb and flow is causing fewer problems than in the past.

In South Africa, the country’s health systems would quickly send notice if COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths were on the rise, says Waasila Jassat, a public-health specialist at the country’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg. “That doesn’t seem to be have been the case for many, many months,” she says.

In the year and half since Omicron emerged, COVID-19 deaths remain stubbornly high and the toll has been around ten times higher than that typically caused by influenza, says Wenseleers. But, still, large infection waves are causing smaller ripples in hospitalizations and deaths. “It gives most people the hope that, in the coming years, the net toll of COVID will get comparable to influenza,” he says.

More News

Hacking the immune system could slow ageing — here’s how

How artificial intelligence is helping Ghana plan for a renewable energy future

Editorial Expression of Concern: Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase – Nature