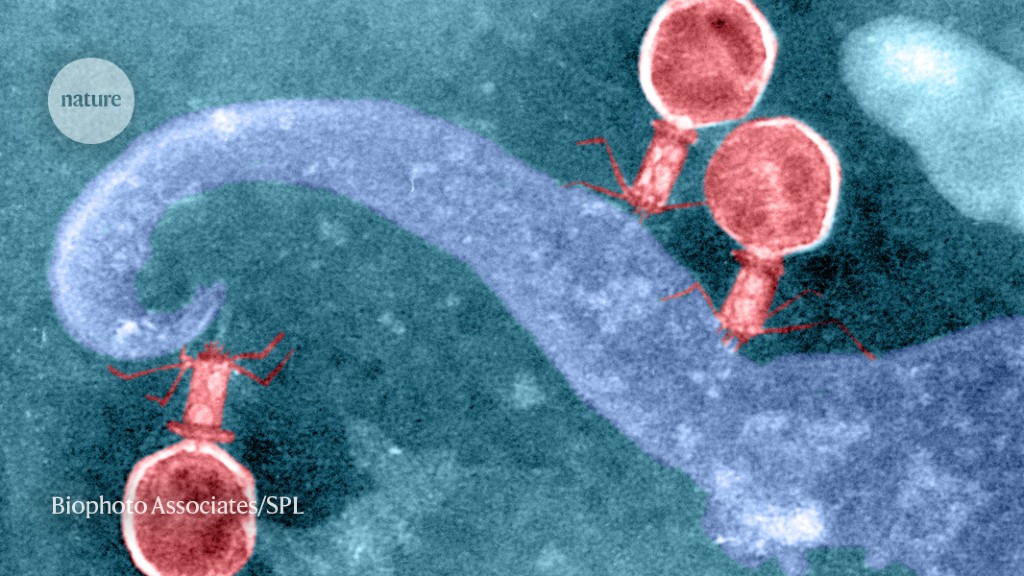

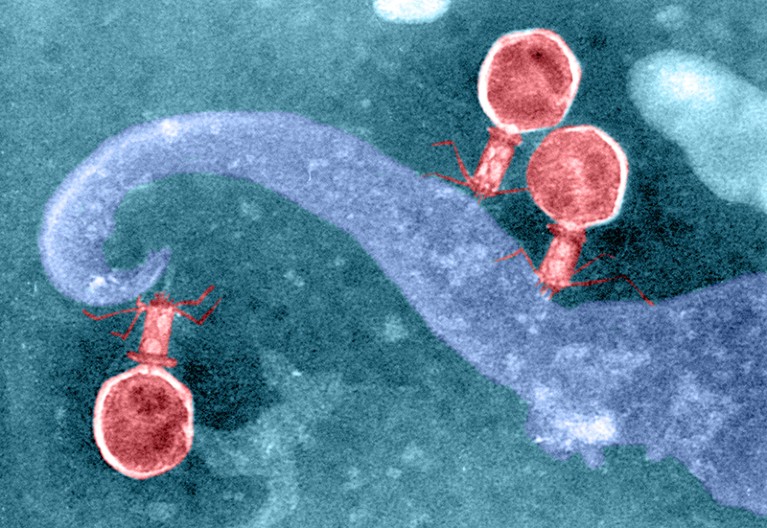

Phages (seen here attacking a bacterial cell) might use CRISPR–Cas systems to compete with one another — or to manipulate gene activity in their hosts.Credit: Biophoto Associates/SPL

A systematic sweep of viral genomes has revealed a trove of potential CRISPR-based genome-editing tools.

CRISPR–Cas systems are common in the microbial world of bacteria and archaea, where they often help cells to fend off viruses. But an analysis1 published on 23 November in Cell finds CRISPR–Cas systems in 0.4% of publicly available genome sequences from viruses that can infect these microbes. Researchers think that the viruses use CRISPR–Cas to compete with one another — and potentially also to manipulate gene activity in their host to their advantage.

Some of these viral systems were capable of editing plant and mammalian genomes, and possess features — such as a compact structure and efficient editing — that could make them useful in the laboratory.

“This is a significant step forward in the discovery of the enormous diversity of CRISPR–Cas systems,” says computational biologist Kira Makarova at the US National Center for Biotechnology Information in Bethesda, Maryland. “There is a lot of novelty discovered here.”

DNA-cutting defences

Although best known as a tool used to alter genomes in the laboratory, CRISPR–Cas can function in nature as a rudimentary immune system. About 40% of sampled bacteria and 85% of sampled archaea have CRISPR–Cas systems. Often, these microbes can capture pieces of an invading virus’s genome, and store the sequences in a region of their own genome, called a CRISPR array. CRISPR arrays then serve as templates to generate RNAs that direct CRISPR-associated (Cas) enzymes to cut the corresponding DNA. This can allow microbes carrying the array to slice up the viral genome and potentially stop viral infections.

Trove of CRISPR-like gene-cutting enzymes found in microbes

Viruses sometimes pick up snippets of their hosts’ genomes, and researchers had previously found isolated examples of CRISPR–Cas in viral genomes. If those stolen bits of DNA give the virus a competitive advantage, they could be retained and gradually modified to better serve the viral lifestyle. For example, a virus that infects the bacterium Vibrio cholera uses CRISPR–Cas to slice up and disable DNA in the bacterium that encodes antiviral defences2.

Molecular biologist Jennifer Doudna and microbiologist Jillian Banfield at the University of California, Berkeley, and their colleagues decided to do a more comprehensive search for CRISPR–Cas systems in viruses that infect bacteria and archaea, known as phages. To their surprise, they found about 6,000 of them, including representatives of every known type of CRISPR–Cas system. “Evidence would suggest that these are systems that are useful to phages,” says Doudna.

The team found a wide range of variations on the usual CRISPR–Cas structure, with some systems missing components and others unusually compact. “Even if phage-encoded CRISPR–Cas systems are rare, they are highly diverse and widely distributed,” says Anne Chevallereau, who studies phage ecology and evolution at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris. “Nature is full of surprises.”

Small but efficient

Viral genomes tend to be compact, and some of the viral Cas enzymes were remarkably small. This could offer a particular advantage for genome-editing applications, because smaller enzymes are easier to shuttle into cells. Doudna and her colleagues focused on a particular cluster of small Cas enzymes called Casλ, and found that some of them could be used to edit the genomes of lab-grown cells from thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), wheat, as well as human kidney cells.

CRISPR ‘cousin’ put to the test in landmark heart-disease trial

The results suggest that viral Cas enzymes could join a growing collection of gene-editing tools discovered in microbes. Although researchers have uncovered other small Cas enzymes in nature, many of those have so far been relatively inefficient for genome-editing applications, says Doudna. By contrast, some of the viral Casλ enzymes combine both small size and high efficiency.

In the meantime, researchers will continue to search microbes for potential improvements to known CRISPR–Cas systems. Makarova anticipates that scientists will also be looking for CRISPR–Cas systems that have been picked up by plasmids — bits of DNA that can be transferred from microbe to microbe.

“Each year we have thousands of new genomes becoming available, and some of them are from very distinct environments,” she says. “So it’s really going to be interesting.”

More News

Judge dismisses superconductivity physicist’s lawsuit against university

Future of Humanity Institute shuts: what’s next for ‘deep future’ research?

Star Formation Shut Down by Multiphase Gas Outflow in a Galaxy at a Redshift of 2.45 – Nature