US demand for weight-loss drug Wegovy has been so strong that its maker has effectively limited the number of people who can start taking the drug.Credit: EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

A new generation of drugs is revolutionizing the treatment of obesity and astonishing researchers with their potency. The drug semaglutide, for example, enabled one-third of clinical-trial participants to shed at least 20% of their body weight1. Tirzepatide, a competing therapy, achieved similar results in more than half of study participants2.

Despite their high effectiveness, researchers are learning that these drugs are not necessarily the solution for everyone living with obesity. “Everybody wants to try them but not everyone responds to them,” says Andres Acosta, an obesity specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Now that semaglutide and tirzepatide have been around for some time, health-care providers are beginning to identify who is likely to benefit the most from them — and to recognize challenges in the drugs’ use.

Hungry brain or hungry gut?

The drugs act by mimicking a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which is associated with appetite regulation. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved semaglutide, under the trade name Wegovy, for treating obesity. And although the agency approved tirzepatide, marketed as Mounjaro, in 2022 for treatment of only type 2 diabetes, the drug is often prescribed as a weight-loss agent.

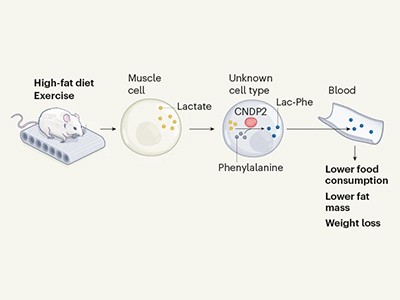

Exercise molecule burns away hunger

Specialists have observed that people’s response to medication depends on the underlying cause of their obesity. Such observations have prompted Acosta and his colleagues to develop a method to tailor the medications to each individual3. The team classified people with obesity into four subtypes: those who need to eat more to reach fullness (which the researchers called hungry brain); those who reach fullness with a regular-sized meal, but feel hungry again soon (hungry gut); those who eat to cope with emotions (emotional hunger); and those with a relatively slow metabolism (slow burn).

People with a hungry gut, who tend to get hungry in between meals, seemed to respond best to the new drugs, according to anecdotal observations by Acosta and his team. Acosta says that the reason is not clear, but that he has a hypothesis. “We think that these patients have low levels of GLP-1 hormones and that’s why they have obesity. And when you give them the replacement, the GLP-1 analogues, they do extremely well.”

At Mayo Clinic, practitioners have used these criteria to guide treatment with an older GLP-1-mimicking drug called liraglutide. A study led by Acosta found that after using liraglutide for a year, participants with hungry-gut obesity lost twice as much weight as those from a general population of people with obesity3.

Full up

Beverly Tchang, an endocrinologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, says that Acosta’s team was the first to subdivide obesity into these categories. Her own anecdotal experience leads her to agree that people with the hungry-gut phenotype tend to do well when taking the GLP-1-mimicking drugs. Data from other groups also support Acosta’s hypothesis4. “We do know that semaglutide slows down the gut and does improve measures of fullness,” she says.

Because of their weekly regimen, the drugs are also benefiting people with erratic schedules and work shifts, notes Peminda Cabandugama, an endocrinologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and a spokesperson for The Obesity Society. Some of the other medications have to be taken at a certain time of day, he says, and “that can be difficult” for those with irregular sleep schedules.

Lifelong regimen?

Researchers hope to learn not only who is most likely to benefit but also how long people should take these medications. A clinical trial5 showed that participants who stopped taking semaglutide after 20 weeks regained most of the weight they had initially lost, whereas those who remained on the medication continued to lose weight. Acosta says that obesity is now understood as a chronic disease and these medications are being recommended for the long term. “Now, do we know what long term means? I think nobody knows and I hope it’s not for life. But those are studies that need to be done.”

Obesity: The fat advantage

Another challenge, according to Tchang, is that these drugs are so efficient that practitioners are starting to discuss how much weight loss is too much. Weight loss leads to a reduction in both fat and muscle, she says. And muscle loss raises the risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and other disorders — an especially problematic outcome for older people and those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. Such populations are subject to what’s called the obesity paradox, a correlation between weight loss and a higher rate of death.

When treating these at-risk people with the new drugs, providers are beginning to target the resolution of obesity-related problems, such as sleep apnoea, fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes, rather than aiming for a marked weight reduction. To achieve that balance, specialists such as Tchang are increasingly exploring the possibility of prescribing lower doses.

“We want to find a place where we are treating a person for health, to prevent disease and to improve quality of life,” Tchang says. “It’s not necessarily about getting the most weight loss out of them.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive