Helmeted hornbills (Rhinoplax vigil) eat fruit and so are key to seed dispersal. Over-trading in this species is likely to damage its native ecosystem.Credit: Tim Plowden/Alamy

Every year, more than 100 million plants and animals are traded legally and illegally around the world. But whether this is sustainable remains hotly debated by researchers. A study published on 26 July in Nature1 sheds some light on the issue by creating a global map of ecosystems’ resilience to current levels of wildlife trade.

The findings could help to show conservation scientists and policymakers where to focus resources, by identifying the hotspots where wildlife trade could cause the most damage.

Major wildlife report struggles to tally humanity’s exploitation of species

“It’s one thing to say, ‘we know that trade is unsustainable’,” says study co-author Oscar Morton, a conservation biologist at the University of Sheffield, UK. “It’s another thing to say, ‘we know what happens to ecosystem X when we take out species A’.”

For example, he says more than one million tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) — small, colourful lizards common in southeast Asia — are traded every year as pets. But whether that volume of trade is sustainable is unknown.

Whole-ecosystem effects

When measuring the overall sustainability of the wildlife trade, individual species cannot be considered in isolation, says Morton. Yet it’s so complex to analyse the impact of the industry on ecosystems as a whole that few attempt it.

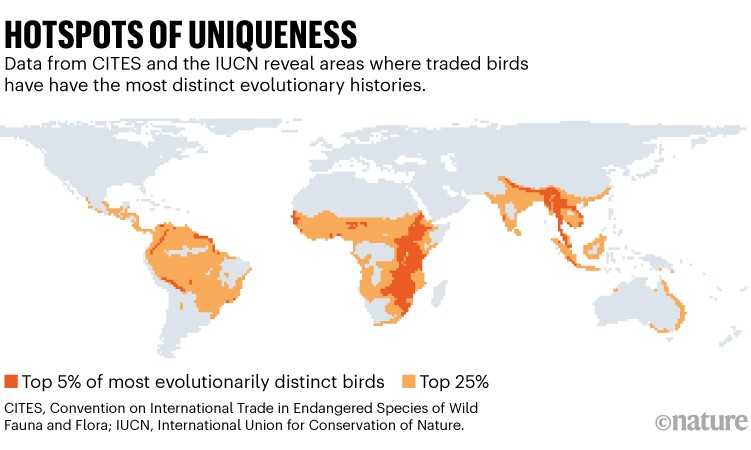

Morton and his colleagues addressed this gap by collating data on the legal trade in birds and mammals collected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and legal and illegal trade from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The researchers overlaid this information on maps of the distribution of various species across the world.

Source: Ref 1.

They added data on the phylogeny of species — their evolutionary histories — to indicate whether each has unique traits (See ‘Hotspots of uniqueness’). They also included information about the species’ functional role in the ecosystem — for example, whether it is a large predator or a tiny grazer. “In a healthy ecosystem, you want a wide range of traits, because then they do all of your ecosystem services — so seed dispersal, carbon stocking, pest control,” says Morton.

The resulting maps allow the team to visualize the potential impact of removing a species from an ecosystem.

For example, hornbill birds are heavily traded for their casques, the bony protrusions on their upper beaks. But as large fruit-eaters, the birds have a key role in seed dispersal in their ecosystems. If hornbills were to be depleted from an area, the vegetation would change radically, with knock-on effects for the birds, insects and other animals that inhabit the ecosystem, says Morton.

Damaging trade

The map revealed global hotspots where trade has the most potential to damage, that is, ecosystems where functional and evolutionary diversity was high. “It’s an impressive piece of research that brings together a huge amount of data,” says Vincent Nijman, a specialist in wildlife trade at Oxford Brookes University, UK. He says the map clearly shows that in relatively small areas of the world, the industry could put ecosystems at risk. He points to parts of Africa and southeast Asia as being important hotspots.

Ivory hunting drives evolution of tuskless elephants

“If we were to be able to pay more attention” to regulating trade in those regions, says Nijman, “then we’re going to get a much better return on our investment”.

International and domestic policies should require assessments of the impact of the wildlife trade on entire ecosystems, says Morton. “We should be looking at ecosystem sustainability as well as species sustainability, when we talk about trade sustainability,” he says.

As well as playing a part in their ecosystems, many species have intrinsic scientific value, says data scientist Mike Massam at the University of Sheffield, a co-author of the study. “We don’t want to lose millions and millions of years of evolutionary history.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive