“AstraZeneca, Moderna, Pfizer! Come and get vaccinated against COVID-19 today!” three nurses shouted through megaphones as they wove through crowds of weekend shoppers in Guatemala City.

This was the scene in February, as health-care workers concerned about the dwindling number of people asking for vaccines took matters into their own hands. Even with the megaphones, however, few listened.

“A lot of people still aren’t getting vaccinated as they think that it’s going to damage their health, kill them, or because their church told them not to,” says Nancy Notz, one of the nurses, who works at a vaccination clinic run by the Guatemalan Institute of Social Security, a government department. “It’s incredibly difficult to convince them otherwise.”

Researchers have been studying vaccine hesitancy in Guatemala, interviewing people to understand their resistance to COVID-19 vaccines and to find solutions. Although the phenomenon is not unique to Guatemala — many people worldwide have rejected COVID-19 vaccines despite data showing they are safe and effective — researchers hope the country’s failures could offer lessons beyond its borders, in preparation for future public-health emergencies.

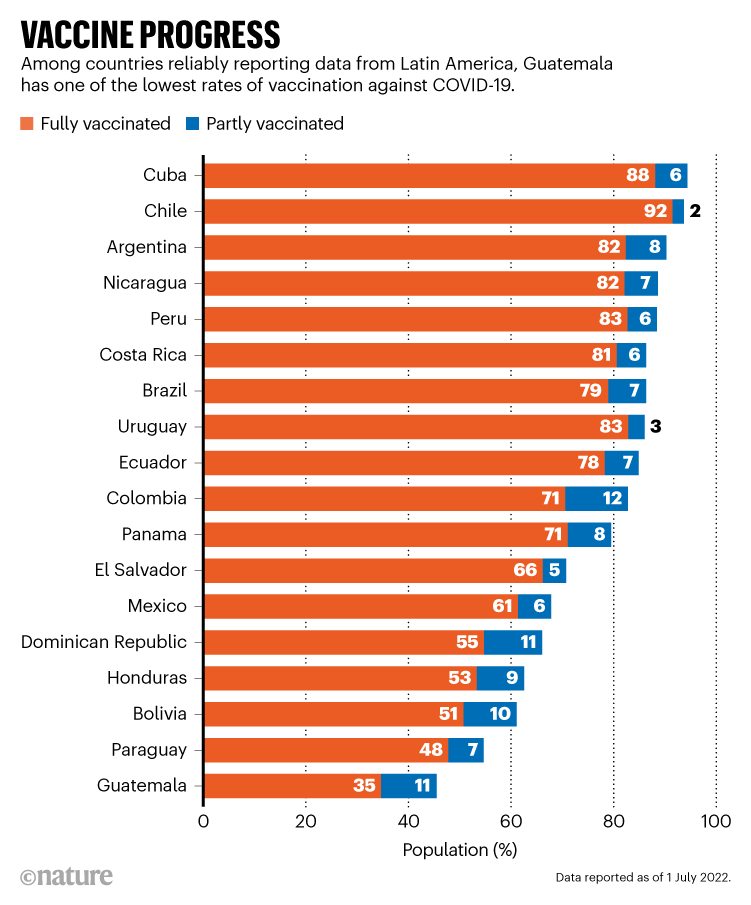

Guatemala has one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates in Latin America: only about 35% of people have been fully vaccinated (see ‘Vaccine progress’). The health ministry has recorded more than 900,000 SARS-CoV-2 infections and 18,500 deaths since the pandemic began. But this is probably an underestimate, because of a lack of testing, says Óscar Chávez, co-founder of the data-analysis think tank Laboratorio de Datos, based in Guatemala City. And that number will undoubtedly rise, he adds, because the vaccination rate is slowing.

The reasons for Guatemala’s hesitancy are complicated, public-health and social-sciences researchers are finding. In some rural regions, only 1 in 4 have received a single dose of a vaccine. Here, factors range from health officials not working with community leaders to establish trust to the government not providing clear safety information in residents’ native languages.

In 2018, more than 40% of Guatemala’s 14.9 million people identified as Indigenous — members of the Garífuna or Xinca people, or one of 22 Maya groups. The country has a history of its military committing human-rights abuses against Indigenous communities. That was always going to make vaccination challenging, says Lesly Ramírez, adviser for citizen participation at the Center for Studies for Equity and Governance in Health Systems in Guatemala City.

Past wounds run deep

In October 2021, residents of Alta Verapaz — a remote central region, with the country’s lowest vaccination rate — were angry when a mobile unit of nurses arrived with COVID-19 vaccines. The residents destroyed the doses, beat the nurses and threatened them, according to local reports.

The incident is symbolic of the government’s failure to consider Guatemala’s ethnic diversity when rolling out vaccines, researchers say. Indigenous groups in the country are deeply suspicious of physicians because of a history of ethical violations by medical authorities. And they carry even deeper mistrust of the military because of the human-rights violations committed by soldiers during a decades-long civil war that ended in 1996; during the early 1980s alone, the government-backed military killed an estimated 200,000 Indigenous people and displaced another 1.5 million.

In some areas, such as Petén in the north, people have seen the army murder their parents, says Mónica Berger González, an anthropologist at the University of the Valley of Guatemala in Guatemala City. So when the army arrives to deliver vaccines, she says, “of course [people are] not going to show up for vaccines. They’re going to hide.”

Fear of vaccines themselves also plays into Guatemalans’ hesitancy. The World Health Organization’s Americas branch, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in Washington DC, commissioned a team of researchers to conduct surveys in 2021 of Guatemalan households about their attitudes toward COVID-19 and vaccines. The effort was supported by Guatemala’s health ministry.

In a report not yet published, but seen by Nature, about 54% of the households polled worried about harmful vaccine side effects, says Berger González, who is a co-author. She adds that people in some communities mistakenly thought that their friends or family members were dying when they developed a fever after vaccination, a common side effect.

Failing to educate Guatemalans about the side effects that are a normal reaction to the COVID-19 jabs increased scepticism, Ramírez says. “Guatemala’s message was too simple: ‘The vaccine is good, go get it.’”

Alex Petzey Quiejú, an independent anthropologist and a member of the Tz’utujil, a Maya community that originated in the southwest of the country, agrees. “They never gave us good information,” he says. “The state’s view of the issue is clouded by its own privilege. They don’t understand us.”

A spokesperson for the Guatemalan health ministry says that many “cultural and religious factors” have contributed to vaccine hesitancy in Guatemala’s people, and points out that “wrong or malicious information” was distributed by groups, including community leaders, making residents reluctant to get jabs.

Communication breakdown

Languages threw up yet another barrier. Between them, Guatemalans speak 25 languages in various dialects. Yet educational material such as pamphlets, posters and radio segments promoting COVID-19 vaccines were at first published exclusively in Spanish; the government requested that they be translated into all languages in November 2021.

The health ministry spokesperson says that this did not prevent local health authorities from translating information prior to the request. The PAHO report found that of the 27 regions surveyed, only 10 had translated materials for their local populations by November 2021.

Where the Guatemalan government was slow to inform rural communities about vaccines, disinformation was quick to fill the vacuum, Berger González and others found. In particular, religious groups discouraged people from getting vaccinated. In the PAHO report, 12% of people surveyed who declared they wouldn’t get vaccinated said it was because they trusted in God to protect them.

Guatemala’s patchy vaccine roll-out is the result of failing to come up with a comprehensive strategy that included Indigenous leaders and communities, says Nancy Sandoval, president of the Central American and Caribbean Association of Infectious Diseases in Guatemala City.

“The health ministry only comes to impose itself and never listens,” says Petzey Quiejú, who has been studying vaccine hesitancy. In cases where researchers have sat down with community leaders such as priests and comadronas – traditional Maya midwives — to discuss community concerns, they were able to increase vaccine uptake, he adds.

The health ministry says that it “has worked hand in hand and in coordination with other state institutions, economic and educational sectors, as well as local and community leaders.”

Logistical failures

Guatemala has struggled to make vaccines available consistently to all its people. The PAHO report found that when vaccination sites ran out of doses and turned people away, word spread quickly, deterring others from trying to visit.

For Indigenous people, the majority of whom live below the poverty line, vaccination sites are often a costly bus ticket and an hour or more’s journey away. And time off of work is a big expense. “It’s the choice between getting vaccinated or buying a kilo of corn,” Petzey Quiejú says.

The health ministry points out that there are currently 1,188 vaccination “posts” around the country, including fixed sites, vaccination brigades and house-to-house sweeps. “Every effort has been made to bring [vaccines] to the most remote sites,” the spokesperson says.

Marginalized communities elsewhere in the world have seen vaccine hesitancy arise because of some of the same barriers observed in Guatemala. In Black communities in the United Kingdom1 and the United States2, for instance, the logistics of accessing COVID-19 vaccines and a historical mistrust of the government and medical authorities have been deterrents.

Researchers in Guatemala hope that successful local solutions — such as creating community networks to build trust — can be used across the country and maybe farther afield.

This simple strategy of getting community representatives to sit down and talk with outsiders has worked in some Indigenous communities, Petzey Quiejú says. “And if it works in one, it will work in the rest. You just have to adapt it.”

More News

I study artefacts left in prehistoric caves

How artificial intelligence is helping to identify global inequalities

Tackling ‘wicked’ problems calls for engineers with social responsibility