Curious Devices and Mighty Machines: Exploring Science Museums Samuel J. M. M. Alberti. Reaktion (2022)

Yes, the Apple iPhone changed the world. Yes, it belongs in a museum. So, of the 38 models produced so far, and the billions of handsets sold, which should be preserved? How do curators choose? And what does the choice say about them, their museums, their nations and science?

Samuel Alberti, director of collections at National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh, contends that even though most science museums these days strive for neutrality, their decisions about collections are always political, reflecting world views, social priorities and sources of funding.

In Curious Devices and Mighty Machines, he digs into this and other paradoxes of Western collecting. Museums must remain fun and accessible, while representing complex concepts. To engage audiences, they need to describe history while being contemporary and relevant. They can store, care for and display only a limited number of objects, but must use these to represent extensive scientific achievement.

Hidden treasures series

Alberti travels across Europe and North America, visiting institutions positioned as science museums (rather than museums of natural history) and talking to curators. Through the lens of a few dozen artefacts plucked from collections tens or hundreds of thousands strong, he explores the museums’ history, the process of collecting, storage and conservation, the planning and staging of exhibitions, and how museums engage with users and the wider public. Freeze-dried transgenic mice lead to a discussion on ethics and intellectual property; the control panel from a particle accelerator, still covered in sticky notes and leftover pens, opens a window on the very human nature of scientific activities. He touches on how many institutions are today grappling with their difficult past.

Engaging the public

Western science museums had a slow start in the cabinets of curiosity of sixteenth-century Europe, accessible only to the wealthy and well-connected: Cosimo I de’ Medici, duke of Florence, kept a collection of mathematical instruments in his palace. A more democratic approach can be traced to the French Revolution. In 1794, Catholic bishop and equality advocate Henri Grégoire founded the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Paris. Open to all, it was meant to demonstrate revolutionary progress to the workers with its “models, tools, drawings, descriptions and books”. But it was another upheaval that triggered the greatest boom in science museums: the Industrial Revolution.

Interactive exhibits, such as this one on sediment motion at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, California, let visitors play with ideas.Credit: Matthew Millman/New York Times/Redux/eyevine

As nineteenth-century governments and philanthropists cottoned on to the vast financial rewards that could be gleaned from the proceeds of science and engineering, institutions dedicated to scientific education popped up across the wealthy world. Most were (and are) concerned more with the tangible machinery of industry — think steam engines and model ships — than with the intricacies of fundamental research. Into the mid-twentieth century (with pauses for a couple of world wars), they strove to showcase the future and brag about national accomplishments.

But progress moves fast. Without constant acquisition, shiny machines quickly slide from cutting edge to curio. Science museums became history-of-science museums with a reputation for stodginess — showcases for sextants and astrolabes. In the 1960s, the fashion turned to ‘science centres’, where visitors could learn through hands-on experiences rather than case-bound artefacts, notably at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, California. Today, science museums endeavour to integrate history with learning and public engagement.

In recent decades, curators have had to grapple with how to collect and display digital media. The video game Grand Theft Auto has cultural significance, but the disc it comes on doesn’t make much of an exhibit — it seems “taxidermized”, Alberti writes. And logistical problems can stymie attempts to bring such software back to life. Museums need the hardware to play the disc, and the means to convert its contents to other formats when the original becomes obsolete. They might need a manual; some even print out the underlying code.

Building bridges

Alberti’s musings on the delicate calculus of curation are down-to-earth and fascinating. “The canny science curator”, he admits, concerned with storage, cost and longevity, focuses on collecting “material that is old enough to be obsolete but not so old as to be collectable”. However, some vignettes are too niche: it’s exciting to learn that objects might contain explosive gases, but do we need to know which brand of glue conservators prefer?

He touches on how some museums are coming to terms with, and attempting to make up for, the harm they have done in the past. Having come of age in the “payday of empire”, many served the colonial mindset, uncritically making a case for Western technological and moral superiority. They appropriated objects from colonized regions and, through their displays, “were complicit in the construction of physical and cultural hierarchies that underpinned racist thought” until well into the twentieth century at least.

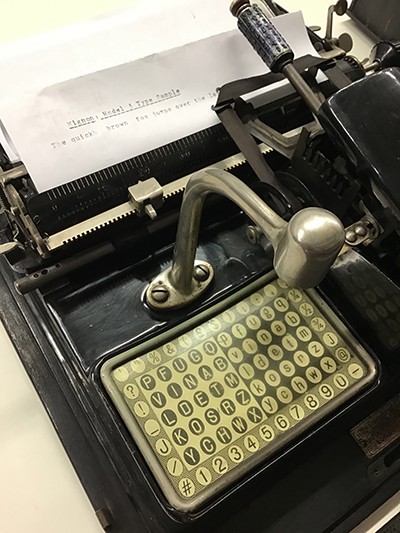

An early typewriter in the collections at National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh.Credit: National Museums Scotland

Some are now seeking to shed light on this past. The Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, UK, for example, explored the links between slavery and the city’s historical cotton trade in its 2018 project Textiles Respun. The Science Museum of Minnesota in St Paul’s ongoing exhibition RACE: Are We So Different? invites conversations about the biological and social realities — and unrealities — of human variation. But Alberti’s discussion of attempts to improve diversity and inclusion in displays, collections and staffing is frustratingly brief.

He does note that museums “are trusted more than most other media” — their expertise is generally respected and considered credible. This allows them to campaign for specific causes, from anticolonialism to climate-change mitigation and dispelling misinformation. In Alberti’s view, strident activism risks threatening or alienating those in rival camps. He argues instead for advocacy: boosting scientific literacy and inviting debate.

Museums, he writes, can help people to make better decisions by “sparking curiosity, and offering tools of discernment”. Never neutral, they should not pretend to be. Instead, they should use their power to build bridges.

More News

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain-of-function’ research

Bird flu in US cows: where will it end?

Daily briefing: Why exercise is good for us