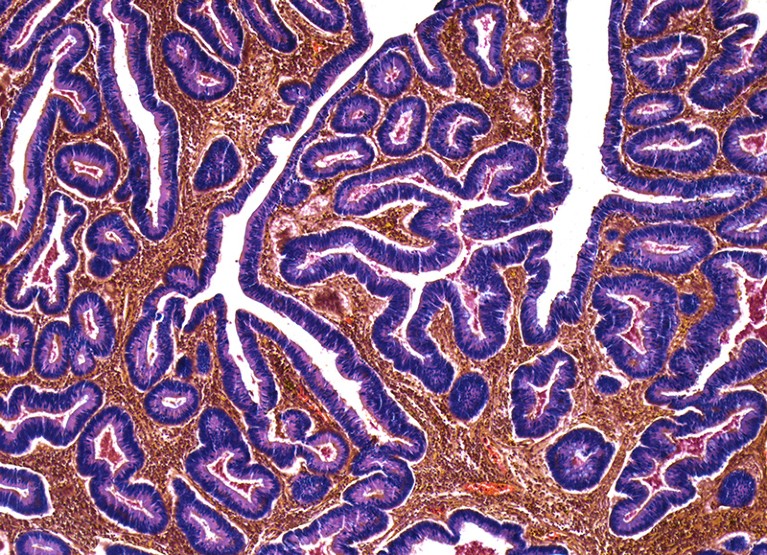

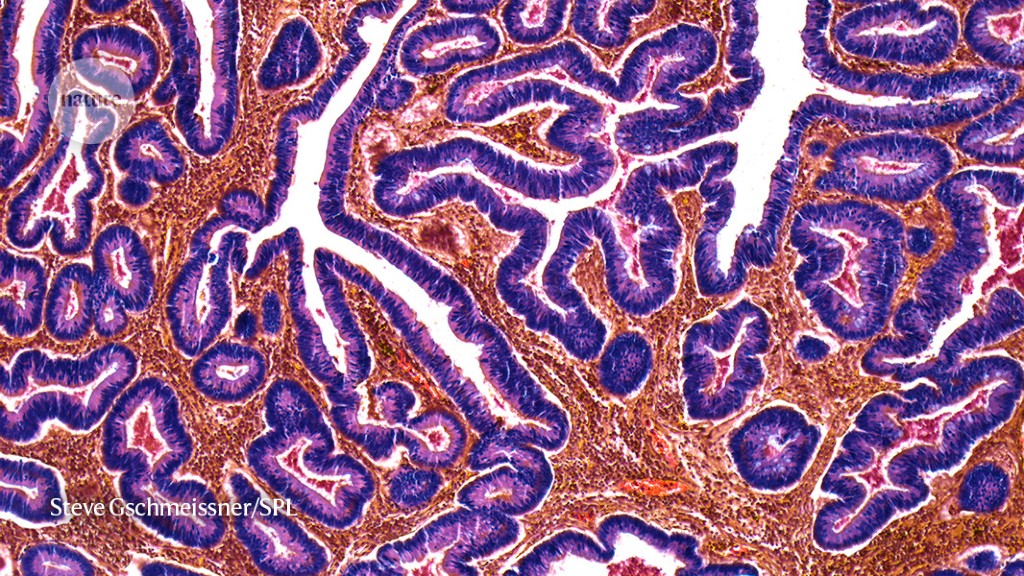

Colon cancer (pictured) is one of several types of cancer that has more severe effects on men than women.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

The Y chromosome could explain why men are less likely than women to survive some cancers, according to studies that combine data from mice and humans.

Two studies, both published on 21 June in Nature1,2, address cancers that are particularly aggressive in men: colorectal cancer and bladder cancer. One study finds that the loss of the entire Y chromosome in some cells — which occurs naturally as men age — raises the risk of aggressive bladder cancer and could allow bladder tumours to evade detection by the immune system2. The other finds that a particular Y-chromosome gene in mice raises the risk of some colorectal cancers spreading to other parts of the body1.

Taken together, the two studies are a step towards understanding why so many cancers have a bias towards men, says Sue Haupt, a cancer researcher at the George Institute of Global Health in Sydney, Australia who was not involved with the work. “It’s becoming clear that it’s beyond lifestyle,” she says. “There is a genetic component.”

Not just lifestyle

Lifestyle has long gotten the blame for the fact that many non-reproductive cancers are more frequent and more aggressive in men than women. Men are more likely to smoke and drink alcohol, for example. But even when such factors are accounted for, some differences in cancer rate or severity between men and women persist3.

(This article uses ‘men’ to describe people with a Y chromosome, while recognizing that not all people who identify as men have a Y chromosome, and not all people who have a Y chromosome identify as men.)

Why the sexes don’t feel pain the same way

Meanwhile, researchers have also found that the Y chromosome, which is often found in men, can be spontaneously lost during cell division. As men age, the proportion of Y-less blood cells increases, and an abundance of such cells has been linked to conditions including heart disease, neurodegenerative conditions and some cancers.

To learn more about how this process might affect bladder cancer — a cancer with a male bias3 — Dan Theodorescu, a cancer researcher at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, and his colleagues studied human bladder cancer cells that had either lost their Y chromosome spontaneously, or had it removed using CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing.

The team found that such cancer cells were more aggressive when transplanted into mice than comparable cells that still had their Y chromosome. They also found that immune cells surrounding tumours with no Y chromosomes tended to be dysfunctional.

In mice, a therapeutic antibody that can restore the activity of those immune cells was more effective against such Y-less tumours than against tumours that still had their Y chromosome. The team found a similar trend in human tumours. This finding is “the most important message” of the study, says Jan Dumanski, a geneticist at Uppsala University in Sweden who was not involved with the research, because it suggests a better way to treat these cancers. Similar antibodies, called checkpoint inhibitors, are already used clinically against some tumours.

Risk from the Y chromosome

In a separate study, a team working on colorectal cancer in mice found that a gene on the Y chromosome called KDM5D might weaken connections between tumour cells, helping the cells to break away and spread to other parts of the body. When that gene was deleted, tumour cells became less invasive, and were more likely to be recognized by immune cells.

Cancer drugs are closing in on some of the deadliest mutations

This also presents a potential target for anti-cancer therapies, says co-author Ronald DePinho, a cancer researcher at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “This is a druggable target.”

The contrast between the two findings — a protective role for the Y chromosome in bladder cancer and a harmful role for a Y chromosome gene in colorectal cancer — emphasizes the importance of context in cancer, says Theodorescu. “Not every tumour is going to have the same biological behaviour,” he says, and researchers will need to look at the effect of losing the Y chromosome on various organs and tumour types.

That context can vary not only on the basis of the organ affected, but even on the tumour’s location in the organ and the presence or absence of other genetic mutations, says Haupt. “You cannot generalize,” she says. “When people just throw all the data together, they miss the point.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive