I have spent a substantial amount of time on a project that was not fun. I did the majority of the work, and it ultimately came to nothing. Finding great collaborators, and being able to work with them productively, is one of the most important predictors of success.

Others’ ideas about what makes the best collaborators are available online, but I’ve never found a tool that fully captured my experiences with picking the right — or wrong — collaborators.

So, on the basis of others’ thoughts and my own ideas about collaboration (and to avoid a repeat occurrence of the project described above), I developed a framework to guide me through selecting the right collaborators and to help others in the same predicament.

Three important traits

Over the years, I’ve found that the people I collaborate with best share three characteristics. A good way to assess potential collaborators’ characteristics is to have a couple of initial meetings before deciding to start the project. These meetings can be used to learn about prospective collaborators’ working styles and ambitions — and to get a sense of how well you ‘click’ on a social level. Usually, this will be enough to gain an idea of how well they live up to these three core characteristics.

Fun to work with. At the end of the day, academics such as myself have the rare privilege of pursuing projects that we find interesting and that we’re deeply curious about. But even the most motivating projects can become a dreaded experience if you don’t enjoy working with your collaborators. Humour and a light-hearted spirit can transform even the most tedious tasks into a fun day at the office or laboratory.

Contributes to work. Ultimately, your collaborator needs to contribute — by both putting in the hours and adding something new and valuable, such as being the prime data cruncher or the paper-writing technician.

Has the same ambition. Research is an intentional process in which you often have an initial idea of a preferred outlet and the scope of the study. Therefore, you and your collaborators will need a shared ambition — otherwise, it might become a source of conflict down the road. For instance, if you dream of having your study grace the cover of Nature, and your partner ‘just’ wants to do a minor book chapter on the study, then you’re severely misaligned in your ambitions.

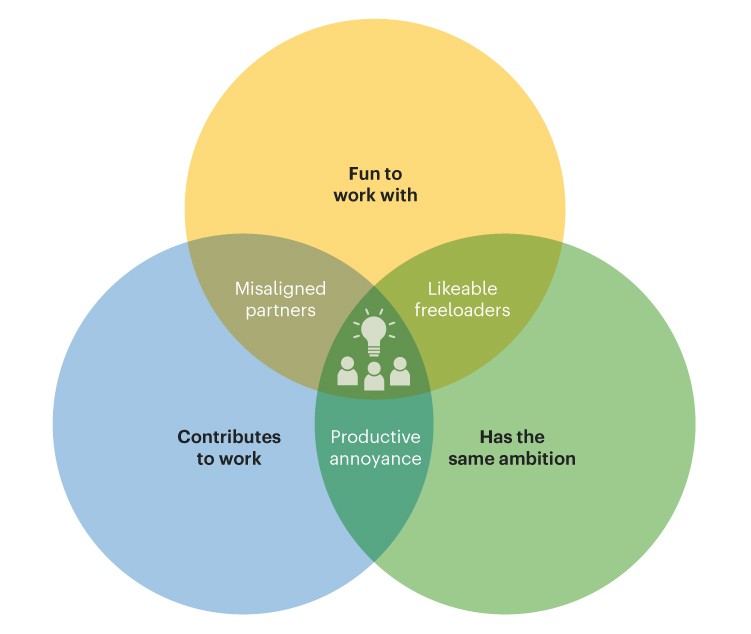

Of course, troubles often come when collaborators exhibit some, but not all, of these characteristics.

For instance, if a person is fun to work with and has the same level of ambition, but doesn’t contribute in a valuable way, then they can be seen as ‘likable freeloaders’. That is, you agree on many things and enjoy working together — but your ‘collaborator’ never really adds anything to the paper other than having their name on it. You could either have a serious talk with that person about their work on the project or simply maintain a social-only relationship.

I’ve encountered people who contributed to a project and shared my ambition, but were generally not fun to work with — making them a ‘productive annoyance’. They can help you progress, but they can also make you miserable in the process — and that’s just not worth it. Either avoid these individuals completely — or ‘shield’ yourself from them by having other, more fun collaborators on the same project.

Finally, you can also have a person who is fun to work with and who contributes to the study, but you simply don’t have the same ambition. This results in ‘misaligned partners’. They have every potential of being a great collaborator — just not on this project. You should instead find common projects for which you have the same level of ambition.

How to use the framework

One purpose of the framework is to assess and pick collaborators. But I found this tool to be more productive when applying it to myself.

How are you perceived as a collaborator? Where would your collaborators place you in the three circles?

When I asked myself this question, it became clear that I’ve always sought to contribute to work, and I try to have the same level of ambition as my collaborators. However, I have, at times, perhaps not been the most fun to work with, making me a productive annoyance to certain collaborators.

Such an insight is both eye-opening and humbling: it can make you feel uncomfortable, because it doesn’t resonate with how you would like to see yourself. But it can result in action towards change. Personally, I’m now more aware of how closely related getting rigorous research done is to having fun in the process. So I try to make fun a priority in my projects.

My core collaborators reside at the intersection of the three circles. They consist of a very small, but highly valued, group of people whom I enjoy working with each day. And I try my best to be a great collaborator for them — one circle at a time.

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged.

More News

Judge dismisses superconductivity physicist’s lawsuit against university

Future of Humanity Institute shuts: what’s next for ‘deep future’ research?

Star Formation Shut Down by Multiphase Gas Outflow in a Galaxy at a Redshift of 2.45 – Nature