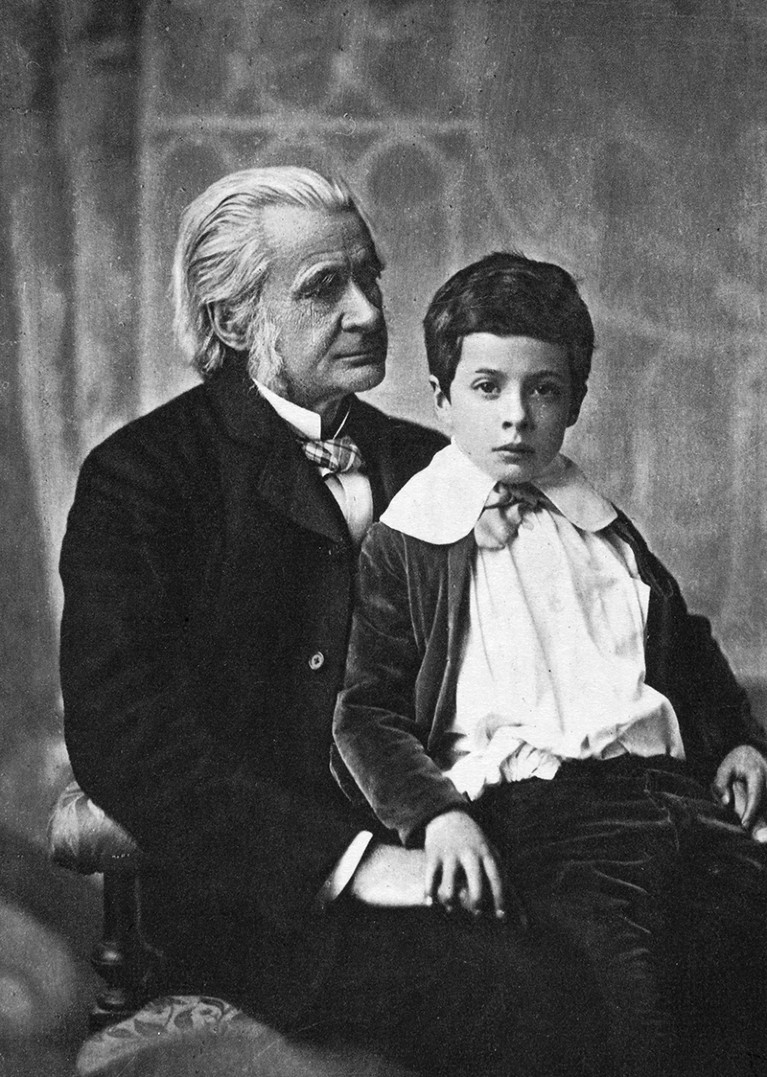

Julian Huxley, grandson of naturalist Thomas Henry Huxley, was instrumental in developing the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1940s.Credit: PAP/Alamy

An Intimate History of Evolution: The Story of the Huxley Family Alison Bashford Allen Lane (2022)

Few concepts have had as important — and vexed — a role in the relationship between science and society as evolution. What it means to be human, our place in nature and how society should be structured: all have been viewed in evolutionary terms. Opposition to evolution is associated with obscurantism and anti-modernism; anti-evolutionist views are squarely outside of the scientific mainstream.

How did a biological theory become such a central part of modern life? In An Intimate History of Evolution, Alison Bashford traces the story from Charles Darwin’s 1859 book On the Origin of Species, through the rise of scientific naturalism in the 1860s and 1870s and the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1940s, all the way to transhumanism, the idea that the limits of our bodies might be transcended. Histories of evolution typically follow its development across a sustained period or use the biography of a key scientist as a case study. Bashford adroitly blends the two methods by surveying the Huxley family across 150 years.

This is no mere conceit. The central figures in this intergenerational study are Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–95), the naturalist and early promoter of Darwin, and his grandson Julian Huxley (1887–1975), the evolutionary biologist who in 1942 codified the modern synthesis by combining population genetics, inheritance and natural selection.

In retrospect: The Courtship Habits of the Great Crested Grebe

The striking similarities between the two lead Bashford to suggest that they might be thought of “as one very long-lived man”. One resemblance was their contradictory morality, which Bashford illuminates but neither condones nor condemns. Thomas called for the abolition of slavery but argued that white people were superior to Black people; Julian opposed Nazism and South African apartheid but was president of the British Eugenics Society from 1959 to 1962.

Bashford’s survey also takes in other members of the dynasty, including Thomas’s other grandchildren. One was novelist Aldous Huxley (1894–1963), author of the 1932 eugenic dystopia Brave New World, about the influence of science on society. Another was physiologist Andrew Huxley (1917–2012), who won a Nobel prize for his work on the propagation of nerve impulses.

Dynastic science

Thomas was a staunch defender of Darwin. In 1860, he was involved in a much-mythologized argument on the subject with a bishop, Samuel Wilberforce, in Oxford, UK. Wilberforce allegedly asked which side of Huxley’s family were apes, and Huxley realized that evolution could usefully be wielded against theologians who strayed into scientific controversy. Research at the time was conducted mostly by gentleman amateurs — in Britain, often Anglican clerics.

Huxley wished to see science under the control of a professional class of trained specialists, not least in the service of colonialist expansionism. In 1864, he joined eight friends, including the physicist John Tyndall and social theorist Herbert Spencer, to form the X Club, an informal pressure group that leveraged its connections and Huxley’s political savvy to shape the direction of Victorian science. Three successive presidents of the UK Royal Society were drawn from its ranks, including Huxley. He wrote an article in the inaugural issue of Nature, the first of many pieces for the journal — a tradition that Julian continued decades later.

Bashford neatly uses the Huxley family to deconstruct the simplistic narrative that evolution “arose suddenly with Darwin, became embattled with theological orthodoxy and then ushered in a secular victory”. Thomas was not persuaded by the mechanism of natural selection, and preferred the idea that evolution occurred by saltation, or sudden mutational leaps. His doubts reflect the wider “eclipse of Darwinism” in the late nineteenth century, when rival evolutionary theories proliferated.

Thomas Henry Huxley with Julian in 1895.Credit: Granger/Shutterstock

Julian was born during this period. Eventually, he would square the circle to explain the mechanism of evolution that had eluded Darwin and left his grandfather unconvinced. In 1900, 40-year-old work by Gregor Mendel on the inheritance of biological traits was rediscovered. Throughout the 1920s, population geneticists including Ronald Fisher and J. B. S. Haldane used mathematical modelling to demonstrate that Mendelian inheritance could explain variation and the results of natural selection on large populations.

Julian’s talent as a communicator and his advocacy were at least as significant as his biological work. He wrote widely on scientific topics for a popular audience, as well as on religion, philosophy and humanism, and even edited a volume on Aldous. A committed conservationist, he was secretary of London Zoo, and the first director of the United Nations cultural and scientific organization UNESCO. This work led to an interest in the emotions of primates, influencing his part in efforts to establish the wildlife charity WWF.

Bashford also explores the wider family and their philosophical milieu. In 1885, Leonard Huxley, son of Thomas and father of Julian, married Julia Arnold, a member of another intellectual dynasty. Julia’s grandfather was Thomas Arnold, a literary scholar and headmaster of the private school Rugby; her uncle was the poet Matthew Arnold; and her sister the novelist and education campaigner Mary Augusta Ward.

Aldous Huxley’s nuclear dystopia at 70: Ape and Essence

Ward and Thomas Huxley were significant voices in the ‘crisis of faith’ that troubled the Victorian intelligentsia. Huxley coined the term agnosticism in 1869 to describe his beliefs. He held that evidence for God not based on empirical data was unknowable, and opposed the intellectual authority of organised religion. But he argued that belief was compatible with “an absence of theology”, and had Leonard baptised, with Darwin as his godfather.

The book is no hagiography. Bashford explores the changes over time in Thomas’s writings on in the superiority of white men. His condemnation of slavery, she argues, stemmed from certainty in his scientific position, rather than principle. She chronicles Julian’s marital infidelity, and shows how his experience with mental illness, personal and among his family, convinced him that it was hereditary and influenced his support for eugenic sterilization. His stature as a scientist, and his family name, lent authority to calls for population control that left a long shadow.

The quasibiographical approach, grounded in a wealth of personal correspondence, makes this history of evolution more accessible and relatable than a history of the idea itself would be. Bashford traces a cultural phenomenon that has profoundly shaped society and revolutionized our understanding of what it means to be human.

More News

Could bird flu in cows lead to a human outbreak? Slow response worries scientists

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

How high-fat diets feed breast cancer