Antarctic Glacier edges closer to collapse

Giant fractures in the floating ice of Antarctica’s massive Thwaites Glacier — a fast-melting formation that has become an icon of climate change — could shatter part of the shelf within five years, research suggests. If that happens, in what had been considered a relatively stable part of Thwaites, the glacier could begin flowing much faster into the ocean, funnelling ice that had been resting on land into the sea, where it would contribute to sea-level rise.

For decades, scientists have carefully tracked changes in Thwaites Glacier, which already loses around 50 billion tonnes of ice each year and causes 4% of global sea-level rise. The latest fractures are deep, fast-moving cracks in its eastern ice shelf. They have appeared in satellite images over the past few years and their growth seems to be accelerating.

“I visualize it somewhat similar to that car window where you have a few cracks that are slowly propagating, and then suddenly you go over a bump in your car and the whole thing just starts to shatter in every direction,” said Erin Pettit, a glaciologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, on 13 December at the American Geophysical Union meeting. If Thwaites’s eastern ice shelf collapses, ice in this region could flow into the sea up to three times faster, Pettit says.

Waning COVID super-immunity raises concerns

Research suggests that protection against the SARS-CoV-2 virus slides over time even in people who have experienced both an infection and had vaccines against it, a combination that initially provides hyper-charged immunity. The research, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was conducted before the Omicron variant emerged (Y. Goldberg et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/g9rq; 2021). But it sharpens questions about how well ‘super-immunity’ — also known as hybrid immunity — will fare against the latest iteration of the coronavirus.

Scientists are now racing to learn by how much Omicron eludes immunity conferred by infection or vaccination. Preliminary results from laboratory studies suggest that vaccination and super-immunity offer some protection against the variant, and that super-immunity might offer more than jabs alone.

However, previous evidence shows that the available vaccines’ potency against other coronavirus variants gradually dwindles, and public-health officials say that Omicron’s spread has heightened the need for people to receive a booster dose. Whether hybrid immunity will prove more durable than vaccines against Omicron is not yet known.

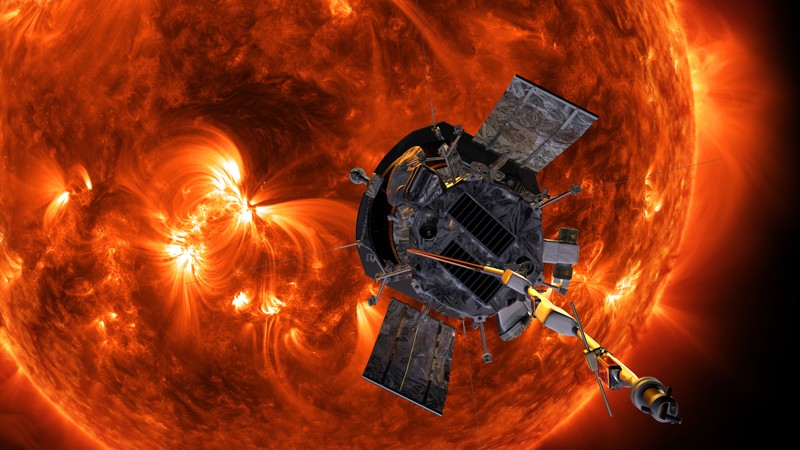

NASA spacecraft ‘touches’ the Sun for the first time ever

A NASA spacecraft has entered a previously unexplored region of the Solar System — the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. The long-awaited milestone, which was reached in April but announced on 14 December, is a major accomplishment for the Parker Solar Probe, a craft that is flying closer to the Sun than any mission in history.

“We have finally arrived,” said Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC. “Humanity has touched the Sun.”

She and other team members spoke during a press conference at the American Geophysical Union meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana, held on 13–17 December. A paper describing the findings appeared that week in Physical Review Letters (J. C. Kasper et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 255101; 2021).

In many ways, the Parker Solar Probe is a counterpoint to NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft. In 2012, Voyager 1 travelled so far from the Sun that it became the first mission to leave the region of space dominated by the solar wind — the energetic flood of particles coming from the Sun. By contrast, the Parker probe is travelling ever closer to the heart of the Solar System, flying head-on into the solar wind and our star’s atmosphere. With this new front-row seat, scientists can explore some of the biggest unanswered questions about the Sun, such as how it generates the solar wind and how its corona gets heated to temperatures more extreme than those on the Sun’s surface.

“This is a huge milestone,” says Craig DeForest, a solar physicist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, who is not involved in the mission. Flying into the solar corona represents “one of the last great unknowns”, he says.

The Parker probe crossed the boundary, called the Alfvén surface, into the Sun’s atmosphere at 09:33 universal time on 28 April. As it crossed the Alfvén surface, the probe flew through a ‘pseudostreamer’ of electrically charged material, inside which conditions were quieter than the roiling environment outside of it.

Since its launch in 2018, the spacecraft has been orbiting the Sun: with each pass, it loops ever closer to the solar surface. It ultimately aims to make 24 close passes of the Sun. It crossed the Alfvén surface on the eighth of those fly-bys.

More News

How mathematician Freeman Hrabowski opened doors for Black scientists

Changemakers — Nature’s new series celebrates champions of inclusion in science

Autistic people three times more likely to develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms