Faleh Tamimi was one week into a sabbatical at Qatar University in Doha when the first wave of pandemic lockdowns hit in March 2020. As countries tried to curb their infection rates, scientists descended on the new coronavirus and quickly began publishing their insights. Tamimi followed with interest. As a dentistry researcher, usually based at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, two details about COVID-19 attracted his attention.

First, the risk of severe illness seemed to correlate with factors such as age, obesity, diabetes, hypertension and smoking. That list struck Tamimi as familiar. Although these factors might suggest cardiovascular disease to some, Tamimi’s mind went to periodontitis, also known as gum disease. Yet, perhaps gum disease and severe COVID-19 both happened to be outcomes of poor overall health.

Then came a second clue.

Studies began linking severe COVID-19 to immune reactions called cytokine storms1 — excessive releases of inflammatory molecules by the immune system — which are also known to occur in people with gum disease. Gum disease arises when too many bacteria accumulate in the mouth. This inflammatory response is actually what destroys the tissue that anchors teeth to the gums. Gum disease has been linked to a number of other inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and arthritis.

Tamimi wondered: was there a connection between oral health and the severity of COVID-19?

He was not alone in his curiosity. Since the start of the pandemic, researchers around the world have been investigating the role of the oral cavity, and its health, in COVID-19 infections. Anecdotal reports of symptoms such as taste loss, which we now know to be fairly common, also point to the mouth’s involvement in COVID-19 infections. As more research is released, these results suggest there’s more to say about the mouth’s influence on COVID-19 infection than initially thought.

The finding could have important implications for public-health advice. “Of all the risks that have been associated with COVID, the easiest one to handle is this one,” Tamimi says. Whereas risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension require medication and lifestyle changes to treat, gum disease can be managed with floss and a toothbrush. “Basically, what we need to do is encourage people to take care of their oral health, and you know, there’s no harm in brushing and flossing your teeth,” he says.

Pairing with periodontitis

In early 2020, this connection was little more than a hunch. But those two pieces of evidence — matching risk factors and cytokine storms — were enough to convince Tamimi to abandon his original sabbatical research plans in favour of studying the link between gum disease and COVID-19 outcomes. Bolstering the case for this study was the fact that he was already in Qatar, which has a fully digitized, public health-care system — and, crucially, one that includes dental care. With collaborators at Hamad Medical Corporation in Qatar as well as in Canada and Spain, the team used digital X-ray records to assess the oral health of 568 people hospitalized with COVID-19 in Qatar.

After adjusting the data for those same risk factors that first intrigued Tamimi, the researchers analysed the correlations between gum disease and COVID-19 complications. They found that people with COVID-19 and gum disease were 3.5 times more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit than were those without gum disease. They were also 4.5 times more likely to be put on a ventilator, and 8.8 times more likely to die2.

“The magnitude was something that we didn’t expect,” Tamimi says, although he cautions that the margin of error for the association with death is large, given that their sample included only 14 deaths. His team is now expanding the study size to around 1,500 people and will look at whether having received routine dental cleanings before contracting COVID-19 affects the outcome of the illness. The team also looked at blood samples from people with COVID-19 for several known biomarkers of inflammation and observed significantly higher levels of inflammation in those with gum disease.

But finding a correlation is just the first step in understanding how oral health affects COVID-19 illness.

“It wasn’t a surprise that COVID could be associated with periodontitis” because there’s a hyperinflammatory response — “even if it’s acute”, says Kevin Byrd, an oral-health researcher at the American Dental Association Science & Research Institute in Gaithersburg, Maryland. The bigger, more difficult issue is working out exactly how the conditions affect each other.

For example, he says, scientists have been studying the association between periodontitis and heart disease for decades and they still don’t know the precise feedback mechanism between the two chronic conditions. Genetic factors that make some people more prone to inflammatory disease than others often complicate matters, he explains. “For new diseases like COVID-19, more evidence is required to determine causation and not merely correlation,” Byrd says.

Virus in the mouth

Around the same time as Tamimi was starting his sabbatical in Qatar, Byrd was working with Blake Warner, an oral pathologist at the US National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research in Bethesda, Maryland, to find out whether COVID-19 outcomes could be linked to the mouth in a different way. Warner says they wondered whether the initial site of infection had an impact on disease severity.

As the largest opening to the body, Warner says, the oral cavity is well-equipped with various immune defences to handle pathogens. This made them wonder whether SARS-CoV-2 infections that started in the mouth might lead to less severe disease than infections that start in the nasal passage and go on to the lungs, an infection route that has received considerably more attention. They realized it would be a challenging hypothesis to investigate — especially because the oral and nasal cavities connect at the back of the throat, allowing for the exchange of aerosols and fluids.

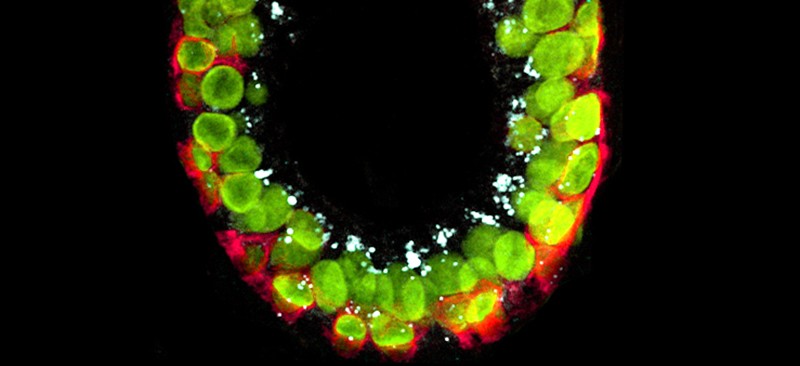

Before studying the possible routes of infection, they first needed to confirm that SARS-CoV-2 could infect the oral cavity. The virus had been detected in saliva in early 20203, but no one had yet shown whether the mouth was a site of infection, although Warner and Byrd were convinced that this was the case. The researchers had seen in their respective RNA sequencing data sets that cells in the mouth expressed the proteins ACE2 and TMPRSS2 — both of which are needed by SARS-CoV-2 to enter and infect host cells.

Warner and Byrd teamed up with other collaborators to conduct a clinical study to analyse samples from people with acute COVID-19 infections, as well as from autopsies of people who had died with the disease. The researchers confirmed the presence of the two entry proteins, as well as SARS-CoV-2-infected cells in the salivary glands and the mucous membrane that lines the mouth, in over half of the patients4. Surprisingly, Warner says, the team also found high levels of viral replication in certain cells in the salivary glands. In another small autopsy study, scientists in Brazil also detected the SARS-CoV-2 virus in periodontal tissue5.

In addition to confirming that the mouth was susceptible to infection, Warner and Byrd’s study revealed two notable correlations between the oral cavity and COVID-19. They saw, in a small group of people, that higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva correlated with disruptions to patients’ sense of taste and smell. The team also demonstrated that saliva from asymptomatic patients could infect cells with SARS-CoV-24, contributing further evidence that the virus can be transmitted by people who show no symptoms of the disease.

Transmission from the mouth

The evidence showing that the mouth harbours SARS-CoV-2 is robust, says Purnima Kumar, a dentistry researcher at Ohio State University in Columbus. Moreover, she adds, reports of oral symptoms such as ulcers and lesions offer further circumstantial support. Given the virus’s apparent presence in the mouth, it’s possible that strategies to lower the viral load in the mouth could suppress viral transmission.

Kumar and her colleagues recently tested one such strategy: mouthwash. In a randomized, controlled trial of about 200 people, the researchers evaluated the effectiveness of four different mouthwash solutions. They found that after 15 minutes, all four mouthwashes decreased the viral load in participants’ saliva samples by up to 89% and then by up to 97% after 45 minutes6.

The authors suggest that mouthwash could help to suppress the contagion and reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission during dental exams. Even though it’s a relatively simple practice, Kumar says, only about 12% of American dentists administer pre-procedural mouthwashes.

Although researchers are starting to chip away at the possible connections between the mouth and COVID-19, other issues are much more difficult to address, Kumar says. One key question, she says, is where in the body does the virus go from the mouth. Researchers do have some theories, however.

A team led by Graham Lloyd-Jones, a radiologist based in Salisbury, UK, and Shervin Molayem, a periodontist and implant surgeon in Los Angeles, has proposed that SARS-CoV-2 can seep through the gums and into the body’s vascular system before circulating to the lungs7. Computed tomography (CT) lung scans of people with COVID-19, Lloyd-Jones says, seem to show that damage is concentrated at the base of the lungs. This is consistent with the virus entering through the blood supply. By contrast, a strictly inhaled pathogen would be expected to produce a uniform distribution of damage.

“At this stage, we’re firmly in the realm of hypothesis,” Lloyd-Jones says. But he has plans to evaluate this route of infection experimentally by taking blood samples from blood vessels between the mouth and the lungs and seeing whether those have higher levels of the virus than do other places in the body. Currently, he’s drafting a proposal for the study with collaborators in India.

Conducting research trials during a pandemic has its own challenges, which some researchers found only drove them to work harder. Warner and Blake recall spending almost every evening on the phone with each other trying to make sense of their data.

Tamimi, who’s now back in Canada, says “this is one of the fastest studies I’ve ever gotten published in my life because we were trying to push ourselves.” As the pandemic continued to cause widespread suffering, he says the team felt compelled to try to help in any way it could. “We’re very motivated.”

Even with scientists working at top speed, it might be a long time before they fully unravel all the ways in which the mouth is linked to COVID-19. Yet if the research shows that maintaining oral health does lower the risk for severe COVID-19, their work could serve as the means to a much needed end. As a researcher, Lloyd-Jones says there are two main questions in his mind. The first is whether his team’s hypothesis about the route of infection is correct. “And secondly,” he says, “can we do anything about it? I think the answer to both of those questions might be yes.”

More News

How AI could improve robotics, the cockroach’s origins, and promethium spills its secrets

Transcriptional control of the Cryptosporidium life cycle – Nature

Heterogeneous integration of spin–photon interfaces with a CMOS platform – Nature