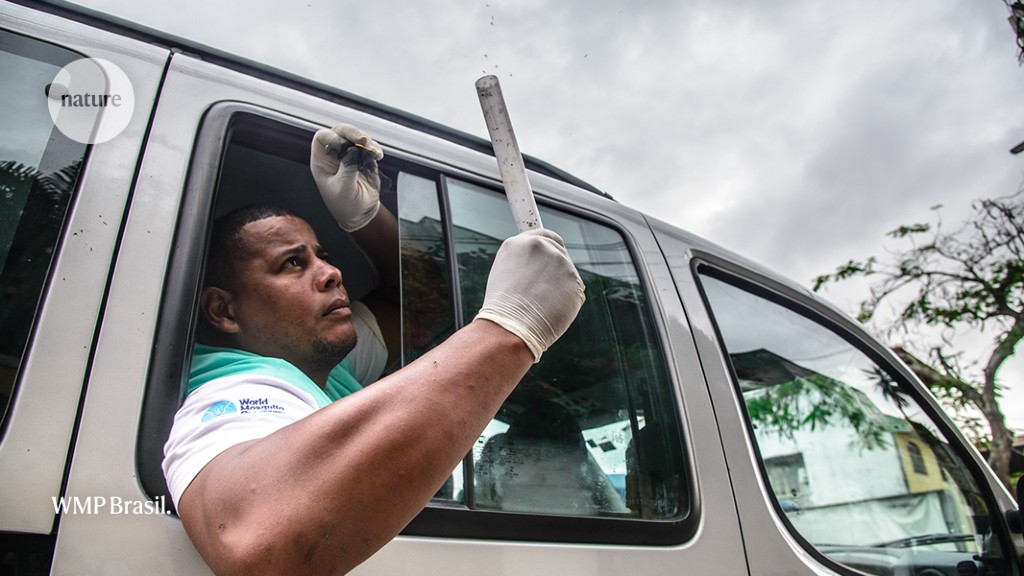

A World Mosquito Program (WMP) staff member releases Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in Niterói, Brazil.Credit: WMP Brasil.

The non-profit World Mosquito Program (WMP) has announced that it will release modified mosquitoes in many of Brazil’s urban areas over the next 10 years, with the aim of protecting up to 70 million people from diseases such as dengue. Researchers have tested the release of this type of mosquito — which carries a Wolbachia bacterium that stops the insect from transmitting viruses — in select cities in countries such as Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Vietnam. But this will be the first time that the technology is dispersed nationwide.

The mosquito strategy that could eliminate dengue

A mosquito factory will be built in a location yet to be determined in Brazil to supply the WMP’s ambitious initiative, in partnership with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), a Brazilian public science institution in Rio de Janeiro. The facility should begin operating in 2024 and will produce up to five billion mosquitoes per year. “This will be the biggest facility in the world” to produce Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, says Scott O’Neill, a microbiologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and head of the WMP. “And it will allow us in a short period of time to cover more people than in any other country.” Brazil has one of the highest rates of dengue infection in the world, reporting more than two million cases in 2022.

Despite the positive results from past mosquito releases, researchers expect that it will be challenging to operate the technology at such a massive scale.

A competitive bacterium

The bacterium Wolbachia pipientis naturally infects about half of all insect species. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which transmit dengue, Zika, chikungunya and other viruses, don’t normally carry the bacterium, however. O’Neill and his colleagues developed the WMP mosquitoes after discovering that A. aegypti infected with Wolbachia are much less likely to spread disease. The bacterium outcompetes the viruses that the insect is carrying.

When the modified mosquitoes are released into areas infested with wild A. aegypti, they slowly spread the bacteria to the wild mosquito population.

Several studies have demonstrated the insects’ success. The most comprehensive one, a randomized, controlled trial in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, showed that the technology could reduce the incidence of dengue by 77%1, and was met with enthusiasm by epidemiologists.

Covering ground quickly

In Brazil, where the modified mosquitoes have so far been tested in five cities, results have been more modest. In Niterói, the intervention was associated with a 69% decrease of dengue cases2. In Rio de Janeiro, the reduction was 38%3.

A WMP worker screens adult mosquitoes at a biofactory in Brazil.Credit: WMP Brasil.

The variation might have to do with environmental differences among the cities — for example, in areas with a larger wild mosquito population, Wolbachia might take longer to spread. But social context is also important. In Rio de Janeiro, flare-ups in violence hampered deployment in some neighbourhoods, for instance. “While we’ve worked very closely with people in those communities, it can be slow work to build trust and to be able to operationalize plans,” O’Neill says.

He anticipates this will be an important challenge as the project expands. “We’re interested in looking into how we can distribute mosquitoes in communities in an automated way that will allow us to cover ground more quickly,” he says. The WMP is testing mosquito-dispersal methods using drones, motorbikes and cars.

Meanwhile, a large randomized, controlled study is underway in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, to compare the incidence of dengue in areas that receive Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes with that in other areas. Previous studies in Niterói and Rio de Janeiro were not carried out in the same way — they didn’t enrol participants and instead used health data from a national database. “We have good indications that the WMP mosquitoes are an efficient tool, but this must be proved beyond any doubt,” says Maurício Nogueira, a microbiologist at the School of Medicine of São José do Rio Preto in Brazil and one of the researchers involved in the study.

First genetically modified mosquitoes released in the United States

Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes have already been approved by Brazilian regulatory agencies. But the technology has not yet been officially endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which could be an obstacle to its use in other countries. The WHO’s Vector Control Advisory Group has been evaluating the modified mosquitoes, and a discussion about the technology is on the agenda for the group’s next meeting later this month.

Despite the mosquitoes’ success, Luciano Moreira, a senior scientist at Fiocruz and one of WMP’s collaborators in Brazil, cautions that governments shouldn’t abandon other public-health measures, such as dengue vaccines. “The Wolbachia method is complementary, and we should work with integrated methods to control dengue, Zika and chikungunya,” he says. “This is not a silver bullet.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive