Metals might be the foundation of the modern economy, but that doesn’t mean they stick around.

A study looking at the economic lifetimes of 61 commercially used metals finds that more than half have a lifespan of less than 10 years. The research, published on 19 May in Nature Sustainability1, also shows that most of these metals end up being disposed of or lost in large quantities, rather than being recycled or reused.

Billions of tonnes of metal are mined each year, and metal production accounts for around 8% of all global greenhouse-gas emissions. So, recycling more metal could help to lower its environmental impacts, says co-author Christoph Helbig, an industrial ecologist at the University of Bayreuth in Germany.

“The longer we use metals, the less we need to mine,” says Helbig. “But before we can identify how to close those loops, we need to know where they are.”

The fact that the economy haemorrhages metals is well documented, says Thomas Graedel, an industrial ecologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Losses can occur at any stage of a metal’s lifespan. Some metals are dug up as by-products during mining but are never made into products. Others are lost during use when components or machinery break apart, or are converted into other substances, such as fertilizers, that are ultimately dispersed into the environment. But the study found that waste and recycling — when metals end their lives in landfill or at recycling plants — accounted for 84% of cumulative metal loss globally.

Most previous studies that attempted to quantify these losses looked at individual metals without examining the wider context, says Graedel. Helbig and his colleagues amassed and compared data from several industries to see how long different metals stayed useful, how they were lost and whether they were likely to be recycled.

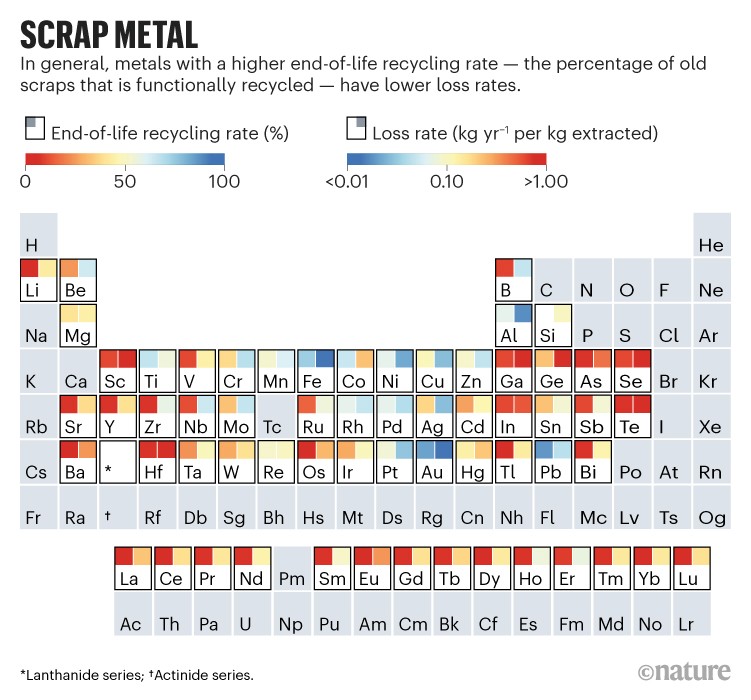

They found that for many metals, only a small proportion is recycled (see ‘Scrap metal’). Exceptions include gold, which stays in use for centuries and can be repurposed many times, as well as iron and lead. Several metals that have been designated ‘critically important’ in the European Union and the United States have high rates of loss and low rates of recycling. These include cobalt, a key component of aircraft engines and lithium-ion batteries, and gallium, which has a crucial role in semiconductors used in mobile phones and other devices.

One way to boost recycling would be to mandate that new products are made with reused metal, says Helbig. For example, the European Union is considering introducing a requirement that some types of battery be made using recycled lithium, nickel, cobalt and lead.

Recycling alloys — mixtures of two or more metals — can be technologically and economically challenging, points out Philip Nuss, an industrial ecologist at the German Environmental Agency in Dessau-Roßlau. Still, giving metals a second, third or even fourth life is essential for building sustainable economies, Helbig says.

More News

Author Correction: A high-density and high-confinement tokamak plasma regime for fusion energy – Nature

Superstar porous materials get salty thanks to computer simulations

Metals strengthen with increasing temperature at extreme strain rates – Nature