Kids have low levels of COVID antibodies

Children infected with SARS-CoV-2 are about half as likely as adults to produce antibodies against the virus, despite having similar symptoms and levels of virus in their bodies, according to a small study in Australia (Z. Q. Toh et al. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e221313; 2022).

The team looked at 57 children with a median age of 4 and 51 adults with a median age of 37, who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in late 2020. They found that children and adults had similar viral loads, but only 37% of the children produced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, compared with 76% of the adults. The findings were published on 9 March.

Researchers say that children could be producing fewer antibodies because they have a more robust innate immune response than adults. This is the first line of defence against pathogens, and is non-specific.

Children could also be better at responding to infections where they enter the body. This means that the body clears the virus quickly and it doesn’t “hang around” to trigger antibody production, says Donna Farber, an immunologist at Columbia University in New York City.

But because antibodies are likely to be important against reinfection, the findings raise questions about how well protected children might be against future infections.

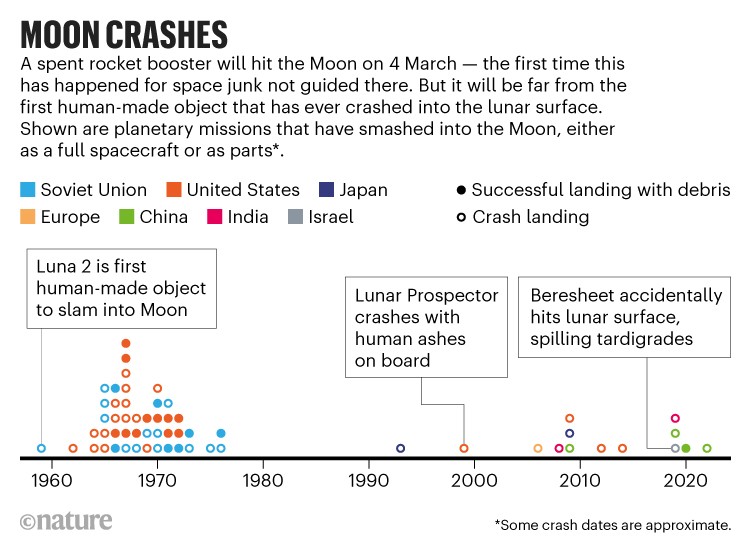

Space junk’s Moon crash adds to 60+ years of lunar debris

On 4 March, humanity set a record for littering, when an old rocket booster smashed into the far side of the Moon. It is the first time a piece of human-made space debris has hit a celestial body other than Earth without being aimed there.

The booster is probably part of a rocket that launched a small Chinese spacecraft, called Chang’e 5-T1, towards the Moon in 2014. Although Chang’e 5-T1 returned to Earth successfully, the booster is thought to have been zipping around chaotically in space ever since. Lunar gravity pulled it into a fatal collision with the far side of the Moon.

The incident posed no immediate danger to humans or other spacecraft, but with at least half a dozen craft scheduled to reach the Moon this year, concern is growing about the lunar surface becoming an unintentional dumping ground.

Plenty of other spacecraft — and spacecraft bits — have hit the Moon (see ‘Moon crashes’). The first was the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 in 1959, which became the first human-made object to make contact with another celestial body when it crashed a little north of the lunar equator. The most recent was China’s Chang’e 5 lander (a different spacecraft from Chang’e 5-T1), which dropped an ascent vehicle onto the Moon in 2020 as it flew lunar samples back to Earth.

Study challenges detection of first stars

The first major attempt to replicate evidence of the ‘cosmic dawn’ — the appearance of the Universe’s first stars 180 million years after the Big Bang — has muddled the picture.

Four years after radioastronomers reported finding a signature of the cosmic dawn, radioastronomer Ravi Subrahmanyan and his collaborators describe how they floated an antenna on a reservoir along the Sharavati River, in the Indian state of Karnataka, in search of that signal. “When we looked for it, we did not find it,” says Subrahmanyan, who led the effort at the Raman Research Institute in Bengaluru, India. The results appeared on 28 February (S. Singh et al. Nature Astron. https://doi.org/hkpj; 2022).

The findings are “a very important landmark in the field”, says Anastasia Fialkov, a theoretical physicist at the University of Cambridge, UK. She and others had been unconvinced that the cosmic-dawn signals were real. The Raman team’s results are the first to put the claim to a serious test, she says — but she thinks that they don’t yet have the power to completely rule it out.

Light from the most ancient stars in the observable Universe has had to travel so far that it is too faint to view directly with ordinary telescopes. But radioastronomers have been looking for an indirect effect, using the spectrum of radio waves. In 2018, astronomers reported seeing a dip in the primordial radio spectrum, centred at a frequency of about 78 megahertz — which the team took to be evidence of the cosmic dawn (J. D. Bowman et al. Nature 555, 67–70; 2018).

More News

The immune system can sabotage gene therapies — can scientists rein it in?

Pollen problems: May brings dismay to a hay-fever sufferer in 1874

Adopt stricter regulation to stop ‘critical mineral’ greenwashing