An unprecedented number of first-time investigators have secured viewing time on NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope in the years since the agency overhauled the application process to reduce systemic biases.

In 2018, NASA changed the way it evaluates requests for observing time on Hubble by introducing a ‘double-blind’ system, in which neither the applicants nor the reviewers assessing their proposals know each other’s identities. All the agency’s other telescopes followed suit the next year.

The move was intended to reduce gender and other biases, including discrimination against scientists who are at small research institutions, or who haven’t received NASA grants before. “The goal of submitting an anonymized proposal isn’t to completely eradicate any evidence of who’s submitting, but rather to have that not be the focus of discussion,” says Lou Strolger, an observatory scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, which manages Hubble.

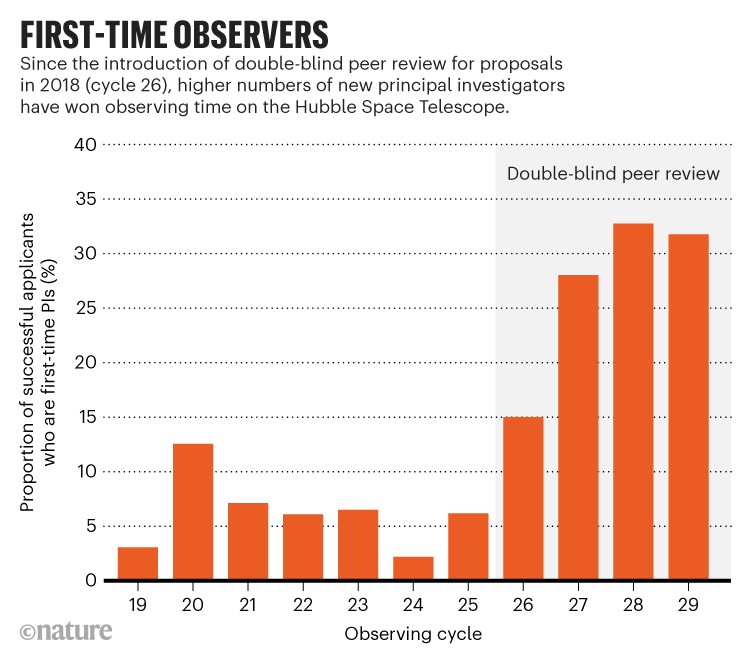

Data from STScI newsletters show that since the change was introduced, more first-time principal investigators have been securing viewing time on Hubble. In 2018, a record-breaking 15% of successful proposals came from applicants who hadn’t been awarded observation time before. That proportion rose to just under 32% in 2021 (see ‘First-time observers’). In 2020, 10% of successful applicants were graduate students, says Strolger.

Increasing numbers of female researchers have also secured Hubble observing time in recent years, according to STScI data seen by Nature. This year, just over 29% of successful applications were from female principal investigators. And in 2018, women had a higher application success rate than men for the first time.

The genders of successful applicants were identified by manually checking their online institutional and social-media profiles, says Iain Neill Reid, associate director of science at the STScI. One limitation of the approach was that, without asking applicants directly, some might have been misgendered. The team did not identify any non-binary applicants.

For other characteristics, such as ethnicity and career stage, there are no official figures, because federal policy restricts the kind of demographic data that can be collected, says Strolger.

More to be done

Double-blind review has the potential to level the playing field for under-represented groups, says Priyamvada Natarajan, an astrophysicist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who was involved in implementing the roll-out of double-blind review at Hubble. But changing the application process is “low-hanging fruit” when it comes to addressing inequities in science, she says. “This is a first step in mitigating biases.”

NASA has rolled out double-blind review to all of its upcoming programmes and instruments. That includes the James Webb Space Telescope, which is set to launch from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana next month.

Until the impact of research that comes out of the observing time can be analysed, it will remain unclear whether the double-blind system has had a positive effect on the impact of science, says Michael Merrifield, an astronomer at the University of Nottingham, UK. “My guess would be that it won’t make things worse, it won’t make things better, but it will be a more equitable system,” Merrifield says.

Since NASA made the change, other organizations have adopted double-blind review systems for allocating telescope time and research grants, Natarajan says. These include the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Garching, Germany, and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

Wolfgang Kerzendorf, an astronomer at Michigan State University in East Lansing who has studied peer review at the ESO1, thinks double-blind review should be rolled out more widely to mitigate biases. “I’m not saying this is the perfect system,” he says. “I believe it’s probably the best system for now.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive