“There was a certain understanding that it could happen in life, it could happen in the streets, and it could happen in different places — but not at a faith site while people pray on a Sunday,” he told CNN. “At the same time, especially around the surrounding Milwaukee areas, there was a heightened sense of political tension with the changing demographics.”

As families of the victims and Sikh civil rights organizations prepare to mark the 10th anniversary of the Oak Creek massacre, they’re calling on elected officials to remember — and to take concrete steps so that another community doesn’t have to endure the same pain.

Sikhs had to fight to be counted

Sikh advocates began working to prevent another Oak Creek from happening right after the attack.

But as community groups including the

Sikh Coalition demanded that political leaders take seriously the threat of extremist violence, they also had to fight simply to be recognized.

About a month after the attack, in powerful

testimony before the US Senate, Harpreet Singh Saini asked the federal government to give his mother “the dignity of being a statistic.”

Saini was 18 when the Oak Creek gunman killed Paramjit Kaur, along with Satwant Singh Kaleka, Suveg Singh Khattra, Ranjit Singh, Sita Singh and Prakash Singh. (Baba Punjab Singh, who survived the attack but was left paralyzed,

died from complications stemming from his injuries in 2020.) Saini’s mother would never see him go to college or get married. His life would never be the same.

Up until that point, the Oak Creek shooting was the

worst hate crime committed in a house of worship since the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama. It seemed clear to Saini that the victims were targeted because of their distinct appearance. Paramjit covered her head with a

dupatta as she sat for morning prayers, while the men wore turbans as symbols of their faith. Still, even though Sikhs had been targets of xenophobia and discrimination since their arrival in the US, the FBI at the time didn’t track hate crimes against Sikhs.

“My mother and those shot that day will not even count on a federal form,” Saini testified. “We cannot solve a problem we refuse to recognize.”

The Oak Creek shooter killed himself, preventing authorities from fully understanding why he acted as he did. But the role of extremist ideology was evident — Jim Santelle, the US Attorney for the Eastern District of Wisconsin at the time, told CNN the

investigation by his office and the FBI found that while the gunman acted alone, “a White supremacist and neo-Nazi background prompted him to make this attack.”

Paramjit Kaur and the others who were killed would not be counted as victims of anti-Sikh hate, but advocacy efforts after their deaths paved the way for change. A year later, the FBI

agreed to add hate crime categories for Sikhs, Hindus, Arabs and other groups — the way it already did for Christians, Jews, Muslims and atheists. The change went into effect in 2015.

It was a small victory in the face of vast, complex challenges. The FBI now collects data on hate crimes and bias incidents against Sikhs and many other marginalized groups, indicating that Sikhs are among the most

frequently targeted faith groups in the US. But the agency does not require law enforcement to submit hate crime statistics — meaning the numbers that are reported are

likely a significant undercount.

“These targeted attacks are happening, and we need a lot more action from elected officials,” said Anisha Singh, executive director of the Sikh Coalition. “We need legislation, we need programs, and we need funding to address these acts of hate violence to get at the core of the problem of violent White supremacy.”

Some warned of right-wing extremism, but were dismissed

Experts across the country had been sounding the alarm on White supremacy and far-right extremism well before Oak Creek.

White supremacist ideology has been around in the US for centuries, and was long a defining element of the nation’s far-right. But in the 20th century, the American far-right grew to encompass factions such as anti-government extremists, neo-Nazis and racist skinheads, according to a 2019

analysis from George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

Mark Potok traces the modern-day domestic terror threat to the emergence of violent, radical right-wing groups — both anti-government and White supremacist extremists — in the 1980s. Far-right ideology and domestic terrorist activity

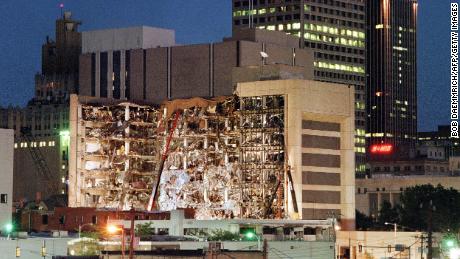

proliferated during the 1990s, culminating with the 1995

Oklahoma City bombing — one of the deadliest acts of homegrown terrorism in the US.

“Many of us in the ’80s and certainly in the ’90s, when the threat was growing very quickly, had lots to say about it and were largely treated like doomsayers and alarmists,” said Potok, a senior fellow at the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right.

Still, far-right ideologies during that period were not mainstream, Potok said. Right-wing extremist violence

decreased in the early 2000s, and the 9/11 attacks prompted law enforcement agencies to concentrate almost exclusively on Islamic extremism, he added.

At the same time, Sikhs — as well as Muslims, Arabs and South Asians — became targets. Long misunderstood in the West, they found that other Americans wrongly associated their turbans, beards and brown skin with the terrorists of al Qaeda.

But as Sikh advocates sounded the alarm on the xenophobia and the violence that these marginalized communities were experiencing, it seemed few were listening.

White supremacist ideas have become increasingly mainstream

Another turning point came in 2008.

Hours after Barack Obama was elected as the nation’s first Black president, three White men set fire to the

Macedonia Church of God in Christ, a predominantly Black church under construction in Springfield, Massachusetts.

In early 2009, Daryl Johnson, then a domestic terrorism analyst at the Department of Homeland Security,

wrote a report warning that homegrown, right-wing terrorism was on the rise. It

noted that “White supremacist lone wolves pose the most significant domestic terror threat because of their low profile and autonomy,” and that returning military veterans were especially vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups.

The report, which was intended for use by law enforcement, was leaked by conservative media, and a

political backlash ensued. Conservatives decried the notion that military members were at risk of radicalization, and accused the report of characterizing right-wing groups with too broad a brush.

Under pressure from Republican lawmakers, the Obama administration

apologized and retracted the report. Efforts to combat domestic extremism were discontinued, and Johnson’s unit was

disbanded.

But many of the report’s assessments proved to be true in this instance. Wade Michael Page, the Oak Creek gunman, was an

Army veteran whose White supremacist views were cemented during his time in the military, according to a

researcher who met and interviewed him. He had long been on the radar of the

Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks extremist groups.

Over the years, White supremacist ideas and sentiments became much more mainstream, elevated in part by Donald Trump’s presidency, Potok said.

On June 16, 2015, Trump

announced he was running for president in a speech that accused Mexico of sending criminals and rapists to the US. The next evening, a

self-declared White supremacist opened fire on a historically Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, and killed nine people. Though the two events were not connected, Potok and Singh pointed to each as examples of racist ideologies gaining ground.

More hate crimes and mass shootings followed — the 2018 attack on a Pittsburgh synagogue by a gunman who targeted Jews online, the 2019 shooting at an El Paso Walmart by a man with hateful views of immigrants and Latinos, and recently, an attack on Black people at a Buffalo supermarket.

But while the lone wolf attacks that once primarily characterized right-wing extremist violence continue, they’ve increasingly been overtaken by organized, paramilitary attacks, Potok said. A once fractured White supremacist movement has coalesced into a unified ideology, he said — one that purports a

massive conspiracy is underway to replace White people in the West.

“Once upon a time, somebody like Wade Michael Page was widely viewed as the lunatic, fringe right — as a racist violence thug who was very unlike most other people around him,” Potok added. “Today, somebody like Page would be part of a much larger scene in the United States and in the West at large.”

That unified movement was on display in 2017, when White supremacists and other right-wing extremists descended on

Charlottesville, Virginia, for a rally that left a woman dead. And it reached a critical mass on January 6, 2021, when tens of thousands of people — among them White supremacists and other far-right extremists —

converged on the US Capitol in an assault on democracy.

The Sikh community is calling for action

US officials and federal law enforcement agencies, Potok said, are now calling this phenomenon what it is: Domestic terrorism carried out by radical, right-wing extremists.

But aside from firearms restrictions and increased intelligence sharing among law enforcement, he sees limits in what can be done to prevent these types of attacks.

“At the end of the day, we’re going through a huge historical transformation in this society and other Western societies, and there’s a reaction to it,” Potok added.

The Sikh Coalition, for its part, sees a few immediate actions to be taken. As community members commemorate 10 years since the Oak Creek shooting, the group is lobbying for three key bills that it believes will reduce extremist violence and make communities safer.

The first one — titled the

Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act — would authorize the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice and the FBI to investigate and prosecute domestic terrorism, as well as require the agencies to submit a joint report on the issue. The bill, which has passed the House, would also strengthen anti-terrorism training programs and create a task force to address White supremacist and neo-Nazi ideology in the military and law enforcement.

“Importantly, it would also do this work without further endangering the Black and brown communities that it is meant to protect,” said Anisha Singh.

The other two bills advocates are pushing are focused on accountability and security. The

Justice for Victims of Hate Crimes Act, which has also garnered support from Jewish and LGBTQ civil rights organizations, would close a legal loophole that prevents law enforcement from prosecuting hate crimes unless bias was the sole motivator — a difficult standard to meet. The

Nonprofit Security Grant Program Improvement Act, which has also passed the House, would enhance a federal program that supports nonprofits, such as houses of worship, in defending themselves against terror attacks.

Kaleka, whose father Satwant Singh Kaleka was killed in the Oak Creek shooting, didn’t want to wait for lawmakers to take action.

A few months after the shooting, he reached out to former skinhead and White supremacist

Arno Michaelis to make sense of why a person might carry out such an attack. The two formed an unlikely friendship and went on to found

Serve 2 Unite, an organization rooted in Sikh principles that seeks to divert young people from violent extremism.

Kaleka and Michaelis have since traveled the country and the world spreading their message of compassion and forgiveness. In talking to at-risk students, they try to instill a “healthy sense of identity, purpose and belonging” — the absence of which leaves people susceptible to violent, extremist ideologies, Michaelis said. They encourage young people to share their grievances, and help channel their energy into projects that have a positive impact on communities.

“There’s got to be some way to get ahead of this and get to the next Wade Page,” Kaleka added.

Scars from the Oak Creek massacre linger

In the immediate aftermath of the Oak Creek shooting, the Sikh community experienced an outpouring of support and attention from leaders and other community members. But as time went on, the attention faded and it seemed that the nation had moved on, Saini said.

For Saini, who lost his mother in the shooting, the issue isn’t just that Americans still don’t have an adequate understanding of who Sikhs are. It’s that in failing to heed the signs after Oak Creek, leaders allowed communities besides his own to endure the same trauma.

“If it was something that people remembered every day, then these shootings wouldn’t be happening,” he said.

On this 10th anniversary, community members in Oak Creek and others from around the country will gather to commemorate the lives that were lost a decade ago. They’ll hold a vigil, invite others to learn more about the Sikh faith and attend devotional services.

But for all the healing that has and will occur, some wounds may never be repaired.

In the spirit of the Sikh faith, gurdwaras are supposed to be open and welcoming to all. But the massacre has forced the community in Oak Creek to be more discerning. The gurdwara there now has cameras installed and a security guard, and visitors can no longer just walk in. The protocol is necessary and now routine, said Saini, but it still saddens him.

“It’s against our beliefs,” he added. “We shouldn’t have to go through this extra security to go to the temple.”

It’s hard to stay hopeful in the face of such challenges. But Saini looks to the concept of

Chardi Kala, loosely translated as striving for relentless optimism, and keeps fighting.

More News

It Took Decades, but Japan’s Working Women Are Making Progress

Kris Hallenga, Advocate for Breast Cancer Awareness Among the Young, Dies at 38

Gaza Isn’t Root of Biden’s Struggles With Young Voters, Polls Show