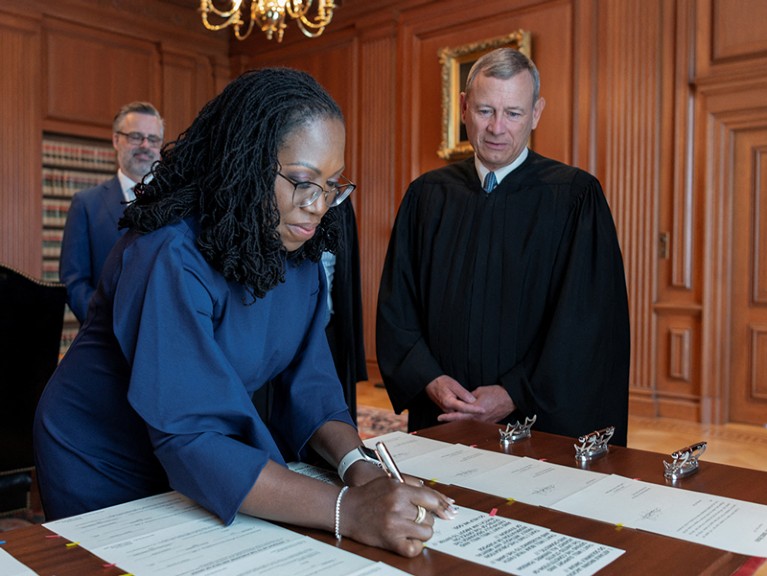

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, seen here with Chief Justice John Roberts, described the court’s decision to end affirmative action in university admissions as the majority ‘pulling the ripcord’.Credit: Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States/Handout via Reuters

The decision of the highest US court to end race-conscious admissions to the nation’s universities was widely expected. Nevertheless, when it came, on 29 June, the verdict shook many in academia, as well as the three Supreme Court justices who voted against the decision. “With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life,” wrote Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, one of two to issue separate dissenting opinions on the verdict.

US to end race-based university admissions: what now for diversity in science?

As Nature reports, the court decided by a majority of six to three that Harvard University, a private institution in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the public University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill violated the Equal Protection Clause of the US Constitution’s 14th Amendment by considering race, alongside other factors such as grades and test scores, in their admissions policies. The decision deprives universities of a crucial tool in the ongoing struggle to establish more-diverse and more-equitable educational environments.

Institutions must now find innovative and alternative ways to continue their efforts to build a more diverse academic environment. This is important not only for moral and ethical reasons: evidence also shows that greater diversity improves all students’ education and leads to increased innovation, which ultimately benefits all of society.

In pursuit of change

Race-conscious policies, also known as affirmative action, were initially established to redress generations of harm that racism had caused to Black people in the United States. They were conceived in the years after Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas, the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling to desegregate schools. Some white-majority communities fought vehemently to maintain segregation. In 1957, the US military was needed to escort the ‘Little Rock Nine’, the first African American teenagers to be admitted to a formerly white-only school in Arkansas.

Affirmative action was an acknowledgement that, without robust efforts to diversify workplaces and student bodies, segregation, although no longer enshrined in law, would effectively continue by default through existing disparities in educational and professional achievement.

It is well established that evaluations of educational achievement based on grades and test scores typically reflect the opportunities that students are afforded, which are inherently unequal. For example, schools that serve predominantly Black and Hispanic communities typically receive thousands of dollars less per student than do those serving predominantly white communities. When researchers modelled the effect of family income on people taking the SAT college-admission test, the negative impacts of low income and poverty on tests scores were amplified for Black students1.

The US Supreme Court is wrong to disregard evidence on the harm of banning abortion

Opponents of affirmative action argue that race should have no bearing on university admissions. But the evidence suggests that efforts to increase diversity by considering other factors, such as socio-economic status, are not having the desired effect. As Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her 69-page dissenting opinion, “Superficial colorblindness in a society that systematically segregates opportunity will cause a sharp decline in the rates at which underrepresented minority students enroll in our Nation’s colleges and universities.”

A real-world example

California offers a case in point. Its public universities were forced by state law to abandon affirmative action in admissions in 1996. In the years that followed, admissions of Black and Hispanic students fell at the state’s most selective universities2. Universities in California and in the handful of other states that banned affirmative action have implemented other measures, including taking economic disparities into account in admissions, to try to improve the diversity of their student bodies. But, as the University of California itself acknowledged in a submission filed to the Supreme Court, these have failed to make their campuses more diverse or more welcoming to under-represented communities.

In a survey of academic researchers released last month by Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature, more than 60% of the almost 5,000 self-selecting respondents reported experiencing some form of discrimination, harassment or bullying at least once a year. That percentage was higher for the small proportion of respondents who identified as belonging to a racial or ethnic minority, and 46% of these individuals said they had experienced some form of race-based discrimination at least once in the past year. Only 56% of respondents said that they were aware of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives or policies at their institutions.

US universities must now carefully consider their position and recommit to enhancing the diversity of their students and faculty members. The fight for equity and inclusion just became harder. But, as Sotomayor noted: “Society’s progress toward equality cannot be permanently halted … The pursuit of racial diversity will go on.”

More News

Could bird flu in cows lead to a human outbreak? Slow response worries scientists

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

How high-fat diets feed breast cancer