A new wave of studies is starting up in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the federally protected right to an abortion.

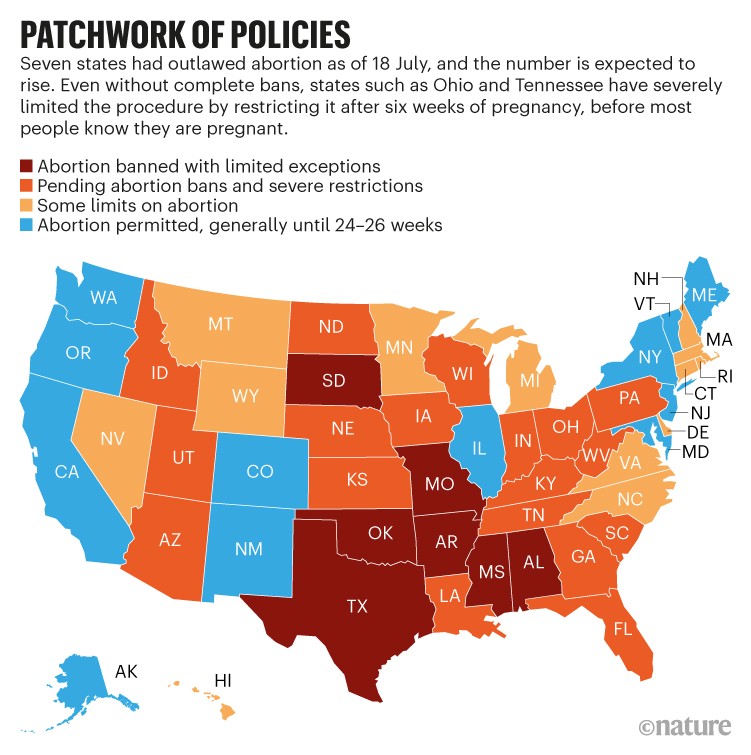

Since the decision in June, seven US states have banned abortion — with extremely limited exceptions — and more than a dozen others that already have several restrictions on the procedure are expected to follow suit. In response, reproductive-health researchers are scrambling to track who is affected and how. In many cases, this means developing ways to partner with communities to collect sensitive information, and to ensure that studies are as useful as possible — particularly to people concerned about their pregnancies.

Although the shifting legal landscape has complicated how reproductive-health researchers conduct their studies, Nature spoke with several who are devoted to the work because it is acutely important as local policies are shaped.

Some acknowledge the emotional toll of this wave of abortion restrictions. Amanda Jean Stevenson, a demographer at the University of Colorado Boulder, says she broke down in tears recently, when she calculated how many more people would die from continuing a pregnancy to term if abortion were blocked in the 26 US states expected to ban the procedure — based solely on the fact that pregnancy and childbirth are much deadlier than abortion. In a paper posted on a preprint server in June, she and her colleagues estimated a rise in yearly maternal deaths as great as 29% in some states1. “Dying when you are pregnant is tragic,” she says. “Dying when you don’t want to be pregnant is sad on another level.”

Bearing witness

For months, many researchers had been predicting the end of the precedent set by Roe v. Wade, the nearly 50-year-old court decision that enshrined the right to abortion in the United States. Last December, the US Supreme Court heard a lawsuit in which the state of Mississippi challenged Roe. Statements from the court’s conservative justices, now in the majority thanks to appointments by former US president Donald Trump, foreshadowed their support for overturning the landmark decision.

By the time that a draft of the court’s decision leaked to the press on 2 May, many researchers had begun talking to abortion clinics and reproductive health-care organizations such as the nationwide non-profit group Planned Parenthood about how they might collect data and enrol participants in studies to monitor the effects of changing laws. They were already seeing alarming signals of what is to come, in data from states with severe restrictions.

In a paper published on 4 July, researchers report a substantial rise2 in dire medical emergencies during complicated births, including haemorrhaging, after Texas’s decision last year to ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy — before most people know that they are pregnant. The authors suggest that physicians failed to intervene quickly during these complications because of state policies threatening to imprison health workers who assist in abortion, unless it can be proved that the intervention is necessary to save the person’s life.

Once Roe was overturned, Ushma Upadhyay, a reproductive-health researcher at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at the University of California, San Francisco, was poised to start counting the number of abortions by state, as laws changed (see ‘Patchwork of policies’).

Other Bixby researchers are collecting data to track what happens to people who seek abortions across the United States — both those who obtain the procedure and those who are turned away as clinics shut down. Every two months, researchers send surveys to participants, including questions such as whether they have travelled to another state to obtain a legal abortion; whether they have taken the medications mifepristone and misoprostol to induce abortion safely, or tried to terminate pregnancies in other ways; and whether they have had health complications as a result of any actions taken. The researchers aim to inform health-care strategies and influence policies to mitigate harm. But most acutely, Upadhyay says, “we are bearing witness by collecting evidence”.

Messy legal landscape

State policies intended to punish individuals who receive abortions, or who help others to get them, are also in flux, following the overturn of Roe. For example, some lawmakers in Texas, where abortion was banned recently, plan to introduce legislation making companies criminally liable if they pay for abortions for their staff, or cover the cost of travel to states where the procedure is legal — as some businesses have promised.

Even before such laws go into effect, says Patty Skuster, a legal researcher at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, research is essential, because legal uncertainty can alter people’s — and companies’ — behaviour, and thereby alter health outcomes. Skuster, who is studying self-managed abortion outside the health-care system, calls for more reproductive-health research in the area of legal epidemiology — the study of law as a factor in the cause, distribution or prevention of harm.

Given that excessive policing and criminalization already impact Black communities disproportionately, many researchers expect legal threats to affect people of colour the most. This would exacerbate other existing disparities: among women living below the federal poverty line, the rate of unintended pregnancies is more than twice the national average, and about one-quarter of people in poverty in the United States are Black.

Bans and legal uncertainty also affect how science is conducted. At the University of Cincinnati in Ohio — a state where abortion is currently banned after the sixth week of pregnancy — reproductive-health researchers are meeting with institutional review boards that monitor biomedical studies and can veto research. The researchers strive to offer the best possible health advice to people participating in studies who are concerned about their pregnancies, but they also want to avoid accusations that they are abetting in an illegal procedure. “We’re in uncharted territory, but academic freedom is an important tenet to hold on to as things change,” says Tamika Odum, a sociologist at the university.

Community-oriented research

Past studies suggest that abortion bans will result in higher rates of maternal death, infant illness or injury and economic hardship. They also predict that health disparities will grow, a troubling forecast given that the rate of maternal mortality among Black women in the United States is already five times the global average among high-income countries. Jamila Perritt, president of the organization Physicians for Reproductive Health, who is based in Washington, DC, says that researchers should seek solutions by partnering more closely with communities than they have in the past.

Odum agrees. “As researchers, we come in with a body of knowledge and ideas about what we think communities need,” she says, and provides an example of how projects can be misguided if researchers aren’t engaged with communities. In one study in Cincinnati, her team wanted to learn why contraception use was relatively low in some communities. At first, the researchers planned to survey people to see how informative pamphlets on contraception could be made clearer. But after deeper discussions with members of the community, the team learnt that some put more trust in advice from their family members than in that from the medical establishment. Now, she says, her research programme delves into how people — especially Black women — interact with the health system and establish trust. “The community showed us what the problem was, and now we can think about how to meet their needs in a different way,” she says.

Odum adds that one advantage she has as a researcher in Cincinnati is a degree of “insider status” as a Black woman and a member of the community she studies. Other researchers are trying to diversify their teams to be more representative of the people most likely to be affected by bans: namely, those who are young, poor, Black or from marginalized immigrant communities.

With Roe overturned, the push to diversify research, improve how scientists partner with communities and disseminate their results has grown more urgent. “As we seek ways to work with communities,” says Perritt, “we need to upend how we think about research, who owns what, who has control of whom.”

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive