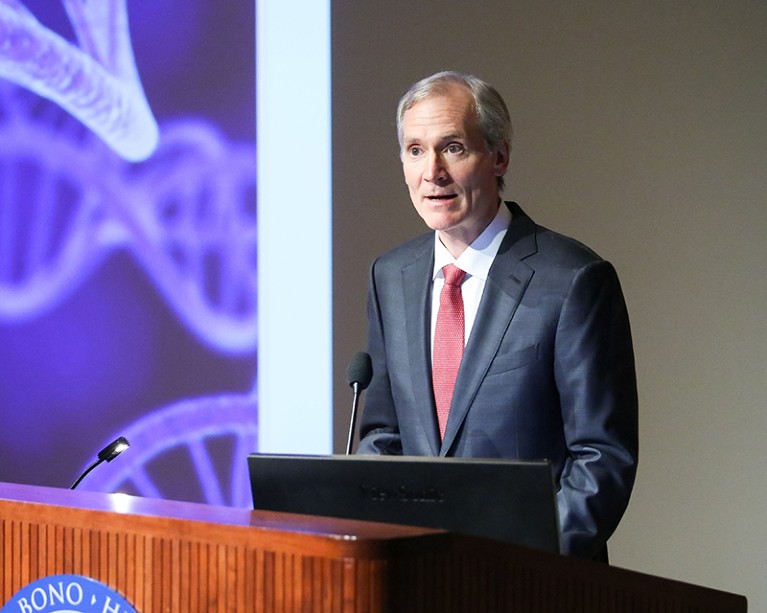

Marc Tessier-Lavigne will resign his position as Stanford University president in August.Credit: Will Ragozinno/BFA/Shutterstock

Prominent neuroscientist Marc Tessier-Lavigne announced last week that he will step down in August as president of Stanford University in California, after an investigation criticized his laboratory oversight and management, but exonerated him of data manipulation. The announcement caps a months-long saga that has gripped researchers worldwide — leaving lab leaders to question their own oversight practices, and reinvigorating conversations about lab culture and the responsibilities of senior investigators.

Publishers unite to tackle doctored images in research papers

An investigation commissioned by Stanford’s Board of Trustees found that members of Tessier-Lavigne’s lab had manipulated data in at least four published manuscripts dating back to 1999, and held Tessier-Lavigne responsible for failing to act “decisively and forthrightly” to correct the scientific record.

The controversy serves as a stark reminder that, ultimately, as principal investigators, “it falls on us”, says Donna Wilcock, a translational neuroscientist at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. “We’re the ones putting our names on our research, we’re the ones funding it.”

Nature spoke to lab leaders about how to safeguard against misconduct in labs, and what should happen when errors or fraud still slip through.

Data review

The report from the Stanford-commissioned investigation found that although Tessier-Lavigne did not himself contribute to the research misconduct or know about it at the time of publication, he didn’t take adequate action to respond to or remedy allegations of data improprieties when they were raised during 4 separate periods over 20 years.

In this time span, Tessier-Lavigne held high-profile positions as head of research at biotechnology company Genentech in South San Francisco, California, and as president of the Rockefeller University in New York City before becoming president of Stanford. He held these positions while running a lab.

Meet this super-spotter of duplicated images in science papers

Some have called into question the feasibility of holding a leading administrative role and simultaneously maintaining proper oversight of research and team members. Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the Science family of journals, published a column on 19 July asserting that running a lab is a full-time responsibility and calling on universities to reconsider hiring researchers into administrative roles if they plan to juggle the two jobs.

Elisabeth Bik, a prominent image-integrity consultant in San Francisco, California, who is among those who have pointed out irregularities in work co-authored by Tessier-Lavigne, agrees. “How could you possibly do both jobs correctly and with the right amount of attention that these jobs need?” she says.

But researchers are often asked to hold administrative roles while running their labs, Wilcock says, and most in such positions — even if they are lower profile than university president — are not accused of research misconduct. “That’s a cop out,” she adds. In particular, researchers of colour often juggle extra roles to improve the diversity of their institutions, and they are expected to do it all, says Monica McLemore, a specialist in reproductive health, rights and justice at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The controversy highlights the importance of senior investigators being present in their labs and hosting regular meetings at which team members can review data, Wilcock says. Her policy is to maintain stringent records in her lab so that she has a rigorous paper trail, and she reviews it regularly.

Embracing failure

The report faulted Tessier-Lavigne for creating a lab culture that fostered an “unusual frequency” of data improprieties. Although several former postdoctoral fellows spoke highly of Tessier-Lavigne, some described a culture that rewarded “winners” — team members who generated favourable results — and diminished “losers”.

How a scandal in spider biology upended researchers’ lives

Bik says this is consistent with her observations in the papers, given that the irregularities happened multiple times over the course of a decade. “It wasn’t just one rogue postdoc,” she says.

Wilcock says it’s important that senior investigators stress to new trainees that experiments sometimes don’t work and that hypotheses are often wrong. But it’s also necessary to celebrate when this occurs, because unexpected results can open other doors, she says. “Science is not about reinforcing dogma; it’s okay to not get the data you were expecting,” she adds. If you create a “pressure-cooker environment in your lab, you’re setting yourself up for failure”.

Lab leaders are often brilliant scientists, but not all are adept at managing and training people, McLemore says. That means institutions should invest more in leadership training for early-career researchers setting up a lab, she says.

Appetite for corrections

Even if lab leaders have put all the safeguards in place, it’s still possible that problems with data — and even misconduct — will arise. What’s important is that the lab leader act decisively to inform journals and take responsibility in those situations, Bik says. It’s not a “badge of shame” to correct the scientific record, says Kim Barrett, vice-dean of research at the University of California Davis School of Medicine. “It’s part of the way that science is supposed to work.”

Dozens of papers co-authored by Nobel laureate raise concerns

But the onus is on researchers to kick-start this process. Without “an appropriate appetite” for corrections, “the often-claimed self-correcting nature of the scientific process will not occur”, the investigation report says. Journals must also respond to these inquiries in a timely manner; some publications’ responses left something to be desired in the Tessier-Lavigne saga, Barrett says.

In 2015, Tessier-Lavigne submitted corrections to Cell and Science, but Science did not publish them owing to an editorial error, it has said, and Cell found that a correction was unnecessary. Both journals added expressions of concern1–3 to the papers last December, after reporting by student newspaper The Stanford Daily renewed concerns about Tessier-Lavigne’s lab.

Tessier-Lavigne also did not follow-up with the journals at the time. Now, he intends to retract the Cell study4 and two papers in Science5,6, as well as correcting two Nature papers7,8. “We are examining the report carefully and will follow up with the most appropriate course of action to ensure the integrity of the scientific record,” says a Nature spokesperson. (Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its journal team.)

When papers aren’t corrected or retracted promptly, there are serious consequences for the research community, especially for those who are early in their career, McLemore says. Tessier-Lavigne’s papers that were ultimately deemed problematic were collectively cited thousands of times, meaning that scientists spent time and resources doing research stemming from falsified data, she says. “We all suffer when we don’t get our science right.”

More News

Finding millennia-old ‘monumental’ corals could unlock secrets of climate resilience

Argentina’s pioneering nuclear research threatened by huge budget cuts

The dream of electronic newspapers becomes a reality — in 1974