Credit: Agnese Abrusci/Nature

Organizational psychology researcher Stephanie Gilbert had prepared for her maternity leave months in advance. She compressed her teaching schedule to complete courses in 7 weeks instead of the usual 12 so that she could take the time off. But on her last day of work in 2017, Gilbert experienced the traumatic loss of her 37-week-old baby. When she returned to her job at Cape Breton University in Sydney, Canada, her research, which had focused on how workplace factors contribute to an employee’s well-being, took a new turn. Spurred by her personal experience, Gilbert began to study how workplaces support — or fail to look after — grieving employees.

There is little empirical evidence to guide employers or colleagues in helping a person who has experienced the death of a loved one or friend, says Gilbert. But grief is a reality that most adults will face at some point. “It is something that people are dealing with more and more with COVID-19,” she says. “But it was always a ubiquitous experience.”

However, assistance for people balancing work and grief is often unstructured. Policies around bereavement leave and paid time off can vary widely, often depending on a person’s career stage or their relationship to the person who died. The irregular schedules and independent nature of academic work might also make bonds between colleagues more tenuous, Gilbert says.

Science careers and mental health

Grief can affect a person’s performance for prolonged periods, and might have different impacts during various career phases. Workplace support for bereaved colleagues must be both proactive and continuous, and needs to go beyond good intentions and condolences, Gilbert says. But often that doesn’t happen, in part because of uncertainty about what kinds of help are needed, and because of a lack of clarity about institutional policies.

In recent years, academics have drawn attention to the workplace support needed for people returning to work after having children and those experiencing other life events, says criminal-justice researcher Emily Cooper at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston, UK. “But I don’t think academia is very good at talking about grief.”

She and others who have experienced the death of a family member or friend while navigating the pressures of academia describe how colleagues could do better by their peers who are in mourning.

Communicate policies clearly

Gilbert’s experience of support was relatively straightforward, because plans were already in place for her to be away for several weeks. When her baby died, her institution said she could use her maternity leave to rest and recover both physically and emotionally. But this is not the norm.

The amount of paid bereavement leave a person can take, and whether they can return to work part-time or in a phased manner, depends on individual institutions. Policies can also differ if an individual’s child has died aged under 18.

Finding and understanding an institution’s policies — and feeling enabled to use them — can seem overwhelming during a time of grief, particularly for early-career researchers who might have shorter contracts or feel less empowered in the workplace than senior faculty members, for instance. “In those early days of grief, it can be very difficult to process and understand what you might need, so there should be ongoing communication,” Gilbert says. “And that communication should inform the work accommodations that are offered for grief and bereavement.”

In December 2021, Cooper’s three-year-old son Alexander had a febrile seizure and died shortly afterwards at the hospital. At the time, Cooper was pregnant and scheduled to be on leave from April 2022. But her employer allowed her to take three months of paid time off starting in December 2021, to be followed by her maternity leave, which enabled her to remain off work until October 2022. “Essentially, I had three months of paid bereavement leave, which is just unheard of in the United Kingdom,” Cooper says.

Her manager also offered her the option of returning to work part-time. “I don’t think they even put it down as anything official,” she says. But knowing she was supported in this way was “a huge relief”, she adds. “We could just focus on what we’d gone through, the other children and just surviving without having to worry financially or anything else.”

The price of grief

Cooper, who has a permanent contract and is the family’s main earner, resumed part-time work in October last year, and returned full time a few months later, in January. But her husband Darren Bowes, who is pursuing a PhD at Lancaster University, UK, had a different experience, and the couple struggled to work out what his funding agency permitted for bereavement leave. “At first, the advice was basically that he should just take holiday or take annual leave,” Cooper says. After discussion with the university, Bowes was granted a month off with full pay and additional time if he needed it.

The lack of clarity around doctoral students’ bereavement benefits is partly because the policies for staff don’t always extend to them, and student policies might apply only to undergraduates. Confusion also emerges when policies cover only specific relationships, as Jenny Fisher, a microbiologist at Indiana University Northwest in Gary, discovered.

When Fisher’s long-time partner had a stroke and died in early March 2020, she received messages of condolence and support. When her partner was in hospital, Fisher checked the official family-leave policy online, but it mentioned only leave to care for a child, parent or spouse — and made no allowances for a partner who was not legally a spouse — so she was uncertain whether she could take any time at all. After he died, she enquired about bereavement-leave policies but found there weren’t any explicitly written. “I wish there had been clearer policies,” she says.

Precarious positions

For Fisher, who was not tenured at the time, the COVID-19 pandemic compounded her uncertainty. Immediately after the week of spring break — the only bereavement leave that Fisher took — her university shut down. Fisher resumed work and moved the three undergraduate courses she was teaching to an asynchronous online format. Although there was no explicit pressure to keep up her work, and she doesn’t doubt that her department would have supported her, Fisher struggled to ask for help. “I don’t know if I didn’t feel like I could ask for help,” she says. “I don’t know how much of it was just my own need to get through, to be able to do things and seem competent.”

When Amanda Moehring’s spouse died in 2020, her university colleagues helped to cover both her professional and personal tasks, including extra supervision of graduate students and grocery deliveries.Credit: Theresa Rice

This pressure to perform can be especially acute for early-career researchers, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers who, in addition to dealing with personal grief, are faced with professional concerns such as short contracts and the need to produce high-quality work quickly, Gilbert says. That pressure is reinforced by academia’s standards: in their work, Gilbert and her colleagues have spoken with pre-tenure faculty members who have struggled to balance the need to take time off for bereavement with expectations about research productivity. Time off can have real repercussions for researchers’ progress, she says, and one person described the negative feedback he received during tenure review as “a kick in the pants from his department after what he’d been through”.

For Fisher, the pandemic led to an automatic extension on the tenure clock, or time window before applying for tenure, but she did not take any extra time off to cope with her loss, in part because she felt a responsibility towards her students. In retrospect, Fisher wishes she had received more proactive support to cope with her responsibilities, and for university policies to be framed with an eye towards “how to give people a break without ruining the experience for the students”, she says.

Cooper remembers the “insecurity and pressure” she felt in the pre-tenure stages of her career, and stresses the need for institutions to be particularly supportive of early-career researchers coping with grief. If she had experienced the loss of her son “while in a precarious job”, she says, “it’s very possible I wouldn’t have stayed in academia”.

Surrounded by support

Assistance from colleagues and institutions is especially meaningful when it is anticipatory and tailored to an individual’s needs. When geneticist Amanda Moehring’s spouse died suddenly in March 2020, her institution — the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada — provided her with proactive and ongoing help despite the pandemic. “The thing that I think my university did particularly well is anticipatory support,” she says. “I didn’t have to ask for anything, aside from telling them that my husband died and I had to go on leave.”

As soon as she did, her colleagues jumped in to help her in her work and personal life, including arranging grocery deliveries and tutors for her children during online school. “It saved me the burden of having to think of what I needed,” Moehring says.

For five months, her colleagues redistributed Moehring’s service and teaching responsibilities to other staff members, and arranged for her graduate students to receive counselling and to be paired with alternative supervisors.

The institution also confirmed that Moehring felt comfortable with the plans, which was as important as providing help. “They took care of things, but they also didn’t do it behind my back,” she says. “I didn’t have to think of coordinating it, but I still felt like I had some say in what was happening.”

Claire Carmalt (left) received care from colleagues when her daughter Tory died in 2022.Credit: Claire J. Carmalt

Those in more senior roles also benefit from proactive support. When organic chemist Claire Carmalt’s daughter died in October 2022, her department at University College London rallied support for her graduate students and to relieve her teaching load. For Carmalt’s extra responsibilities as department head, her institution set up an alternative e-mail address to delegate tasks to others. Carmalt was informed of these changes and let the university know when she was ready to receive those e-mails again. At that point, “the messages of support were actually fantastic”, she says.

Returning to work

Despite her senior role, returning to work was not easy for Carmalt, because, like many in mourning, she was uncertain of her own reactions or how people would react to her presence. “I’ve been there 25 years, but I felt very anxious going back,” she says. “Would I get upset all the time? Would I be able to keep it together in meetings? Make decisions, provide scientific guidance and all of that?”

The accommodations researchers might need when they resume work will vary. Some might prefer to return part-time at first; others might only be able to cope with a subset of tasks or need a private workspace. Communicating about work accommodations is crucial and should be an ongoing discussion, Gilbert says. The deep thinking required to write manuscripts or glean meaning from data can be especially challenging when grieving, she adds, so faculty members and students might prefer to shift their focus towards less intensive tasks, such as data collection.

The price of grief

Teaching a large undergraduate class can seem especially daunting, and many researchers might feel more comfortable resuming mentoring responsibilities and teaching smaller, graduate-level courses. “There’s a great deal of emotional labour required when teaching and dealing with students, and having to maintain that professional appearance,” Gilbert says. “For some people, that can be quite a demand.”

Cooper, for instance, found she isn’t ready to teach yet. “I’m just not in a position to go into a room and motivate a group of students,” she says. She was able to discuss with her supervisor which responsibilities she would resume when she returned to work. “I’ve found it really helpful to still have a voice in the process,” she says.

Department heads and other colleagues can also ease a person’s transition back to work by simply checking in with them about how they might like to be treated on their return and letting other colleagues know, Moehring says. This could be as simple as asking whether a person would like colleagues to acknowledge their loss in the workplace or stick to work topics only, because individual preferences can vary widely.

Having a safe physical space, such as a private office or quiet room, can be helpful because grief can manifest differently each day, Carmalt says. “The problem with grief is, I probably look like I’m fine today,” she says. “But yesterday I was struggling at work. Out of the blue, for no reason, a big wave of grief will come, and trying to fight back those tears can be very difficult.”

It’s also important for managers to keep an open mind about work schedules for several months, particularly because grief can disrupt people’s sleep schedules. Although those in senior roles similar to Carmalt’s can choose to work from home, that might not be the case for postdocs or graduate students working on experiments, she says. “Supervisors need to have some flexibility with understanding that their days are going to be different.”

When a colleague dies

Grief in the workplace is amplified when the person who has died is a colleague.

When Peter Salvino, a graduate student in neuroscientist Lucas Pinto’s laboratory at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, died suddenly in December 2022, Pinto’s department chair told him that he could step away from his teaching responsibilities and committee duties if he needed to. “That was very helpful, and I did take them up on it,” Pinto says.

Alongside his own grief, Pinto found himself needing to support other students and lab members who looked to him for guidance as principal investigator (PI). He spoke to each group member individually to break the initial news and clarified that the lab would support their needs. He gave students the option of working when and where they chose, and coordinated with the university to ensure that counselling services were available to them over the winter break. Because the students were good friends with Salvino, they are motivated to continue his work while coping with grief themselves. “People rally around the desire to see his work through, see his name on publications,” Pinto says. But at the same time, “we’re trying to do our best to just keep going”.

Although the trauma didn’t change Pinto’s approach to mentoring, he has noticed a shift in his interactions with lab members. “I’m always friendly, but this kind of gave me a licence that I didn’t know I needed, to really be myself without the PI sheen,” he says. “It brought into really sharp focus how important it is to have a healthy, welcoming lab environment. Good science follows from that.”

Whether at the level of an individual lab or the broader academic community, solidarity through periods of grief can have lasting benefits for everyone. Supporting employees and colleagues through a traumatic period is likely to pay off in terms of retention and positive job attitudes, Gilbert says.

But, more importantly, she adds: “People deserve to be cared for by their workplace in that vulnerable time.”

More News

Venus water loss is dominated by HCO+ dissociative recombination – Nature

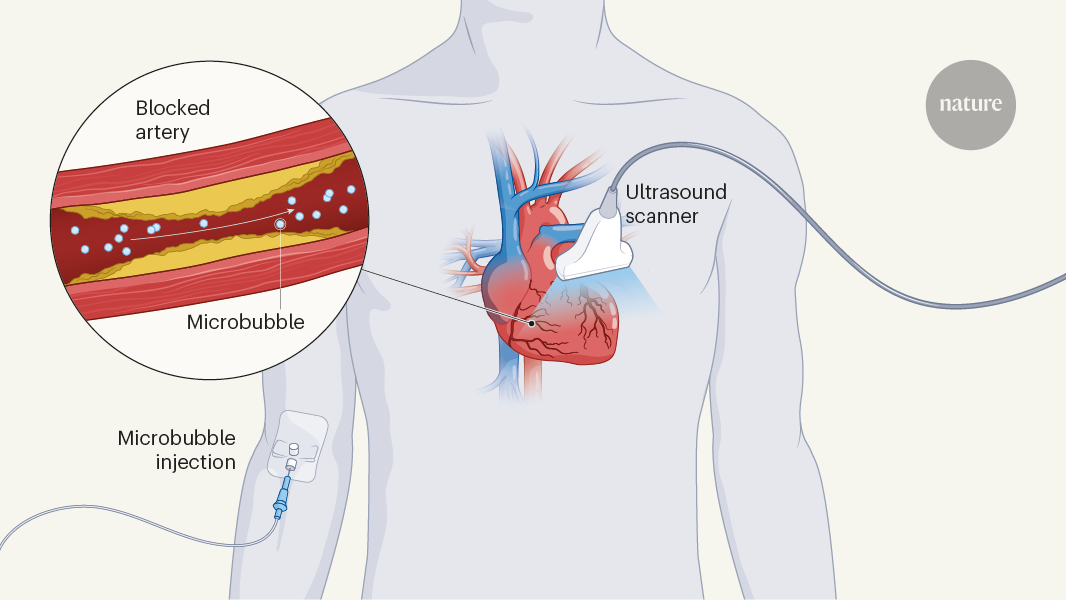

Microbubble ultrasound maps hidden signs of heart disease

I make 3D models of conifer needles to explore their climate effects