I will never forget standing in steamy French Guiana on 25 December last year as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) lifted into the sky on the Ariane 5 rocket. A fortnight later, I watched as the final wing of the telescope’s 18-segment primary mirror, the largest mirror ever built for space, seamlessly expanded into its fully deployed form. And months on, I looked — through teary eyes — at JWST’s first images. I was one of the first people on Earth to see the infrared Universe in high resolution.

For more than six years I have had a front-row seat for NASA’s science programme. Now it is time to give my seat to someone else.

Leading NASA’s Science Mission Directorate has been the job I’ve loved most. Nowhere is there a role that offers more exciting missions or has more potential to affect how we understand the Universe and the world we live in. It was a very difficult decision to resign. But I believe it is the best decision for the agency, for the collaborators, educators and trainees in the NASA science community, and for me.

JWST’s best images: spectacular stars and spiralling galaxies

The past year has been one of the most exciting in the history of NASA science. The JWST has been more successful than anyone could have imagined. Astronomers have been dreaming of such a telescope since 1989, and still it defied expectations, with breathtaking images of star nurseries and the most distant galaxies ever seen. In the five months since the release of its first images, JWST has already started to upend theories of galaxy evolution, changed our understanding of the rate of star formation during the Universe’s infancy, and captured the first evidence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

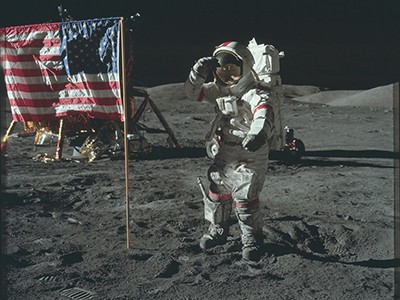

NASA is midway through launching almost a dozen Earth-science missions focused on understanding our life-enabling planet — including a billion-dollar satellite to track the global water cycle in unprecedented detail — and is starting work on the next-generation observatory of the Earth system. We have the world’s largest programme devoted to Earth science in space, and for several years now the US government has invested close to US$2 billion annually in Earth science at NASA; it is currently considering increasing that to at least $2.4 billion. (This budget does not include the work NASA does for the US government in building weather- and space-weather-forecasting systems.) We are on our way back to the Moon with the launch of the Artemis programme and looking ahead to sending people to Mars. And, in humanity’s first planetary-defence test in September, scientists intentionally smashed the DART spacecraft into an asteroid and redirected its orbit.

As NASA’s longest continually serving associate administrator of science, I have been part of incredible missions. Twice I have experienced seven minutes of terror — first when the robotic geologist Insight made its descent to the surface of Mars, then again when the Perseverance rover did the same — with both a success and failure speech in my bag. And I held my breath during our extraterrestrial ‘Wright brothers’ moment, when the team made the first controlled flight in an atmosphere other than Earth’s and flew the helicopter Ingenuity on Mars.

As much as I have enjoyed this, every leader has weaknesses. Over time, their weaknesses weigh more heavily on an organization and it becomes time for someone with fresh ideas to step in. So, when was it time for me to step aside?

Fifty years after astronauts left the Moon, they are going back. Why?

I started by asking myself: was I still learning a lot? And was I still getting better? By ‘better’, I don’t mean approaching perfection or never making mistakes. To me, getting better means enabling breakthrough innovation and making the organization qualitatively and quantitatively stronger. When I could no longer answer ‘yes’ to those two questions, I knew it was time for a transition.

Finding the right time to leave was important not just for me, but also for NASA. I wanted to leave at a time when I was confident in the strength of the organization. An organization is at its most vulnerable during transitions, even if the change stands to invigorate it in the long term. At a US government agency, many transitions tend to happen as a result of the election cycle. As a result, it was important for me to step down well ahead of any such time to avoid stacking major changeovers on top of each other. To prepare for such a transition, succession planning is key. We want to give future leaders the time to learn to lead well before we need them to take over.

Since my resignation announcement in September, I have asked myself every day how I can leave NASA science with a strong foundation. This means talking to my colleagues and leaders at NASA, making sure everyone understands the organization, and trying to foresee potential bumps and empower my colleagues to handle them. I have also tried to solve residual problems, so I don’t hand them over to whoever takes over from me. During the past few months, I have been sharing knowledge I have gained and handing over key partnerships to those who will be filling in, while helping to recruit amazing and diverse candidates for my job.

So, what’s next? Until I turn my badge in on New Year’s Eve, I am running full force towards the cliff edge. Then I will take a break. I have bought a season ski pass for Utah, and I fully intend to spend time with my family and friends before deciding on the next chapter in my life. I am excited about taking a back seat and seeing what NASA science continues to achieve for humanity. This is a job that I will surely miss, one that I tried to do to the best of my ability as a scientist and service-driven leader — from start to finish.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

More News

Daily briefing: Orangutan is first wild animal seen using medicinal plant

Old electric-vehicle batteries can find new purpose — on the grid

Finding millennia-old ‘monumental’ corals could unlock secrets of climate resilience