Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

A donkey-like animal that was highly prized by Mesopotamian elites might be the earliest known hybrid animal bred by humans. Researchers analysed the genome of these ‘kungas’, found buried alongside early Bronze Age royals in what is now Syria. The animals were the offspring of a female donkey (Equus africanus asinus) and a male Syrian wild ass (Equus hemionus hemippus), sometimes called a hemippe. The finding supports cuneiform texts that depict kungas as the product of complex animal husbandry programmes.

Reference: Science Advances paper

Portugal has created the largest fully protected marine reserve in Europe and the North Atlantic. The Selvagens Islands Nature Reserve was formally extended in November from 95 to 2,677 square kilometres to protect the habitats of species such as the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and the blue shark (Prionace glauca). In a letter to Nature, marine ecologist Filipe Alves and three colleagues encourage other nations to follow Portugal’s lead.

Treehugger | 6 min read & Nature | 2 min read (Nature paywall)

Features & opinion

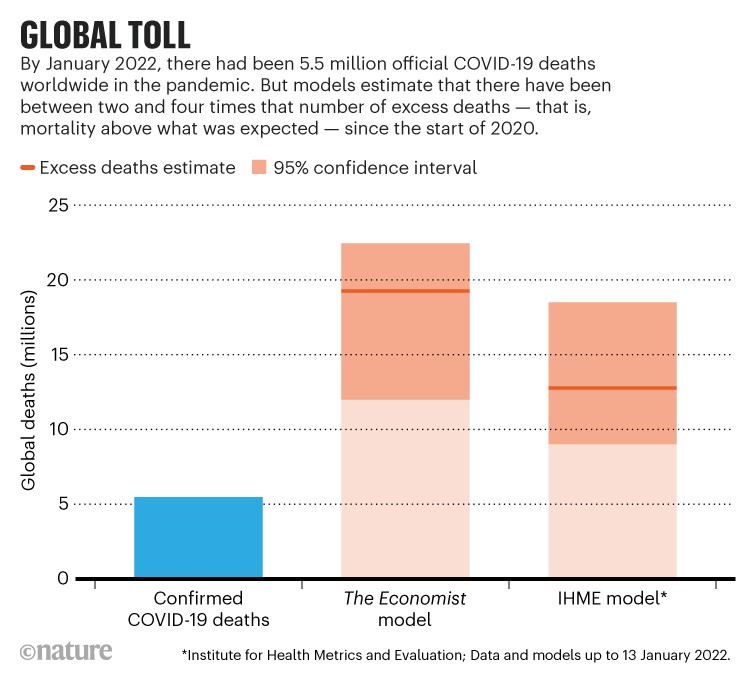

On 1 November, the global death toll from the COVID-19 pandemic passed five million, official data suggested. It has now reached 5.5 million. But that figure is a significant underestimate. Records of excess mortality — a metric that compares all deaths recorded with those expected to occur — show that many more people have died in the pandemic. Working out how many more is a complex research challenge. Some official data are flawed, and more than 100 countries do not collect reliable statistics on deaths at all. Efforts to correct the record use methods including satellite images of cemeteries, door-to-door surveys and machine-learning computer models that extrapolate estimates from available data.

Last week, a US report recommended ways to strengthen scientific integrity and preserve public trust in government. The report followed high-profile examples of attacks on science during the administration of former president Donald Trump — such as ‘Sharpiegate’, when the president showed a map in which the path of a hurricane appeared to have been altered with a permanent marker. Federal researchers who blew the whistle on political interference in science tell Nature why the long-awaited measures are needed.

Reference: White House Office of Science and Technology Policy report

Where I work

In this picture taken in November 2019, anthropologist Lars Krutak listens to Chen-o Khuzuthrupa, a centenarian nobleman of the Chen tribe of northeastern India, describe his tattoo. “He received the tattoo — a tiger stripe motif with circles that represent the spirit — during an elaborate ceremony in the 1930s, when he was a young headhunter and warrior,” writes Krutak. “Anyone could get a tiger spirit tattoo in the style of Khuzuthrupa’s, but much of its significance would be lost without the culture and context around it. The original artist is long dead, and nobody remembers the prayers, songs and other aspects of the tattooing ceremony. The two other men in the village with this particular tattoo are in their nineties. They are the last generation to carry the tiger spirit.” (Nature | 3 min read)

More News

This Earth-like exoplanet is the first confirmed to have an atmosphere

Retuning of hippocampal representations during sleep – Nature

Measurement of the superfluid fraction of a supersolid by Josephson effect – Nature