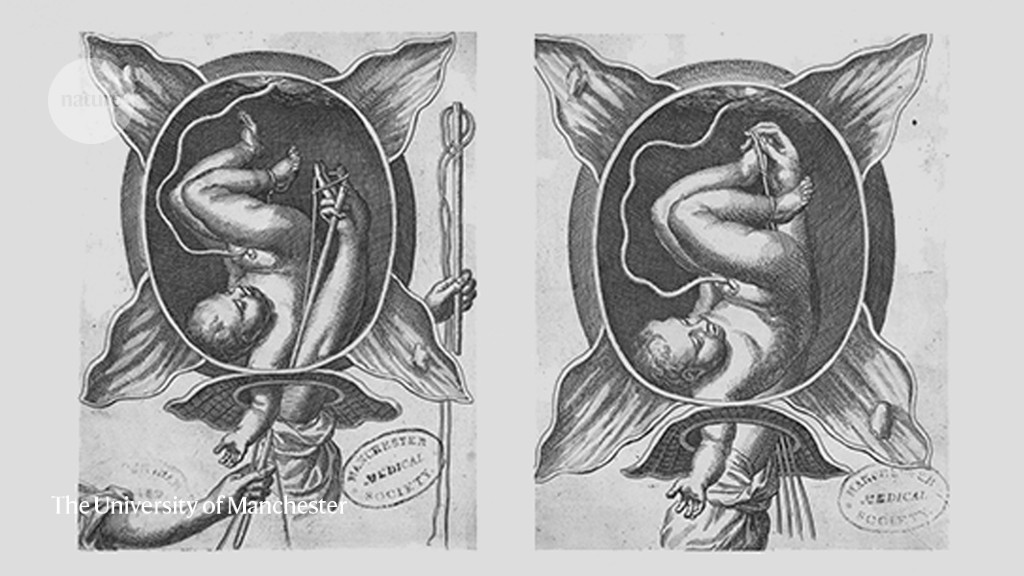

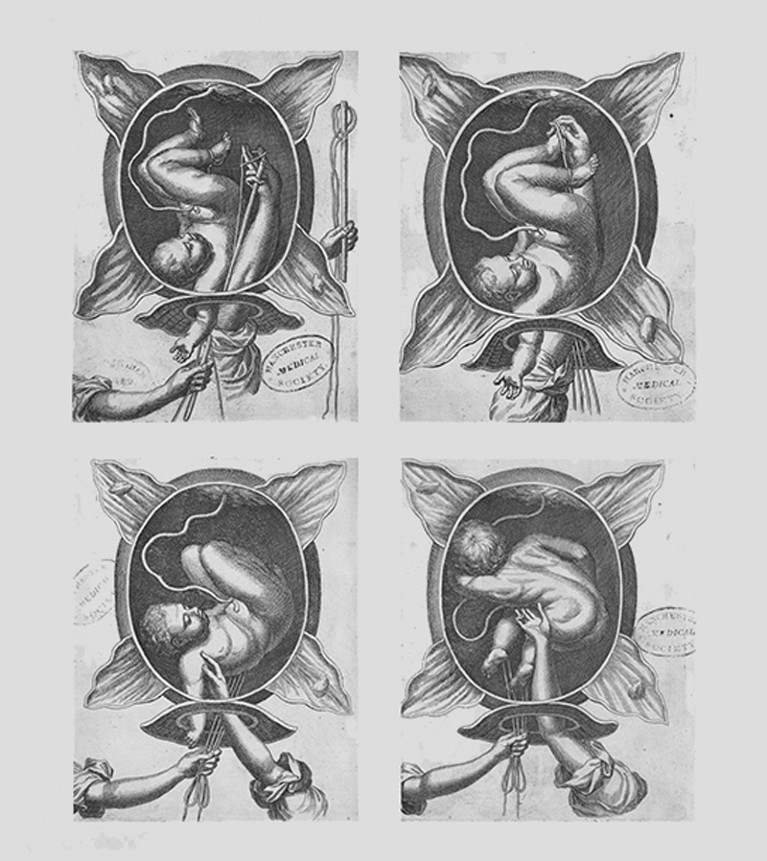

Engravings from a 1690 German medical text by Justine Siegemund.Credit: The University of Manchester

Birth Figures: Early Modern Prints and the Pregnant Body Rebecca Whiteley Univ. Chicago Press (2023)

In 1690, acclaimed midwife Justine Siegemund became the first woman to publish a German medical text. She wrote The Court Midwife, a beautifully illustrated training manual based on her extensive experience delivering babies for both peasant and wealthy women in the city of Lignitz (now Legnica in Poland). “This book, which was long in seeing the light of day, as if in childbirth, will be what I leave to the world, since I have borne no children,” she wrote.

Portrayed in detailed embryological engravings by medical illustrators Regnier de Graaf and Govard Bidloo, the “fetuses depicted stand for all those infants saved by Siegemund herself and by all the midwives who learned from her”, writes historian of medicine Rebecca Whiteley in Birth Figures, a scholarly analysis of drawings of fetuses in utero between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

The controversial embryo tests that promise a better baby

In these times, nothing was seen so much as it was imagined. The earliest ‘birth figures’, woodcuts dating back to 1515, show chubby-cheeked, cherubic infants bouncing, diving and waving inside the womb, itself a balloon-shaped, upside-down flask seemingly detached from the body. Twins are depicted with their arms wrapped around each other’s shoulders, cuddling or with one upright twin grabbing the other’s upside-down ankle, as Jacob did Esau’s in the biblical story of their birth.

The figures in Siegemund’s manual come in intricately drawn series accompanied by precise instructions on how to deliver a baby that is in an unusual position — for example, lying in a transverse position in the womb. In one description and drawing of ‘podalic version’ (the procedure of pulling a malpresenting fetus out by its feet), she explains how a midwife can insert her arm into the uterus, tying a ribbon around the infant’s foot to “keep a firm grip on the slippery leg” and pull the baby out little by little -— a variation on a technique first published by the French surgeon Ambroise Paré in the mid-sixteenth century.

During this early-modern period, female midwives delivered most babies. Whiteley convincingly argues that the profusion of midwifery manuals at this time (with drawings mainly by men), “triggered a change in how midwives both thought about and treated the laboring body”. Even though birth figures were sometimes used to exert “masculine authority” over women’s practice, they also helped midwives to “envision the body, and particularly the position of the fetus, in a newly concrete way”. Moreover, they were accessible to both the learned and the illiterate.

The skills of female midwives such as Siegemund are all the more astonishing given the need to operate purely by touch. Whereas male midwives increasingly used tools such as forceps to deliver babies, such devices were officially forbidden to women. But only female midwives were “entrusted with the right to touch the mother’s ‘privities’ — her labiae, vagina and cervix”.

The effects of overturning Roe v. Wade in seven simple charts

In some ways, skilled midwives of the time might have been more advanced than obstetricians today (although in seventeenth-century London, about one woman died for every 40 births). The podalic version practised by Siegemund has since gone out of fashion. Instead, caesarian sections now account for more than one in five of all childbirths globally, according to the World Health Organization. Although essential for saving lives in cases of prolonged or obstructed labour or fetal distress, these procedures also contribute to higher rates of postpartum maternal complications, including abnormal bleeding, fever and infection.

Obstetric techniques advanced over the course of the nineteenth century, with the development of anaesthesia and (thankfully) antiseptic practice, and those midwifery manuals gave way to contemporary medical textbooks. A Google image search today for “fetal presentation” reveals “numerous contemporary birth figures”, including, Whiteley notes, an amazing array of fetuses in utero in a variety of positions. However, the mother’s body is represented only as a pair of legs, a pelvis, a pair of buttocks or, occasionally, arms and breasts.

Likewise, in the media, pregnant people are frequently represented as a headless, legless pregnancy bump. Whereas early-modern birth figures were used by women to gain knowledge and authority, these modern birth figures have a role in the disempowerment of pregnant people, Whiteley argues. The visual reduction of the pregnant body to the womb and the pelvis erases the mother. That attitude is exemplified, she writes, by anti-abortion politicians who frame fetuses “as independent beings and the primary patients in a pregnancy”.

Now as then, the birth figure remains powerful. It is “the fetus in the womb”, says Whiteley, but “also the person in the world”. The early printed image, as with a moving fetus on an ultrasound, offers joy and connection, but also anxiety, to parents. It empowers, but it can be misused. It is revealing, but also mysterious — a tiny cosmos, in utero.

More News

Author Correction: Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor – Nature

Changing rainforest to plantations shifts tropical food webs

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive