‘Inflammation clock’ can reveal biological age

A new type of age ‘clock’ can assess chronic inflammation to predict whether someone is at risk of developing age-related disorders such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease. The clock measures ‘biological age’, which takes health into consideration and can be higher or lower than a person’s chronological age.

The inflammatory ageing clock (iAge), reported on 12 July in Nature Aging, is one of the first tools of its kind to use inflammation to assess health (N. Sayed et al. Nature Aging https://doi.org/gnzm; 2021). It is based on the idea that as a person ages, their body experiences chronic, systemic inflammation because their cells become damaged and emit inflammation-causing molecules. People who have a healthy immune system will be able to neutralize this inflammation to some extent, whereas others will age faster.

To develop iAge, a team including systems biologist David Furman and vascular specialist Nazish Sayed at Stanford University in California analysed blood samples from 1,001 people aged 8–96 who are part of the 1000 Immunomes Project, which aims to investigate how signatures of inflammation change as people age. The researchers used the participants’ chronological ages and health information, combined with a machine-learning algorithm, to identify the protein markers in blood that most clearly signal systemic inflammation.

People aged 99 years and older who were tested with the tool had an iAge 40 years lower, on average, than their actual age.

The study “is a further reinforcement of the fact that the immune system is critical, not only for predicting unhealthy ageing, but also as a mechanism driving it”, says Vishwa Deep Dixit, an immunobiologist at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Quarter-dose of COVID vaccine rouses response

A preliminary study has hinted at the possibility of administering fractional doses of vaccines to stretch limited supplies and accelerate the global immunization effort. Tests found that two jabs that each contained only one-quarter of the standard dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine gave rise to long-lasting antibodies.

In an early trial of the mRNA-based vaccine, study participants received one of three dose levels: 25, 100 or 250 micrograms. Initially, the 35 participants who had received the lowest dose seemed to have an insufficient immune response. But blood analyses 6 months after the second shot found that nearly all of the 35 participants had ‘neutralizing’ antibodies, which block the virus from infecting cells, the researchers reported in a preprint published on 5 July (J. Mateus et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/gn3t; 2021). Levels of antibodies and T cells were comparable to those found in people who have recovered from COVID-19.

A half-dose now is more useful to an unvaccinated person than a full dose a year from now, says Alex Tabarrok, an economist at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, which means that dose-stretching “is a way of promoting vaccine equity”.

WHO advised to lead on genome-editing policies

A committee has advised the World Health Organization (WHO) to assume a leading, global role in efforts to regulate genome editing. The WHO should help national governments to coordinate their regulations, the advisers say, and genome editing should not yet be used to make modifications that can be passed on to later generations. The team also urged international collaboration in the governance of non-heritable gene editing, which has shown promise in treating disorders such as sickle-cell anaemia and transthyretin amyloidosis.

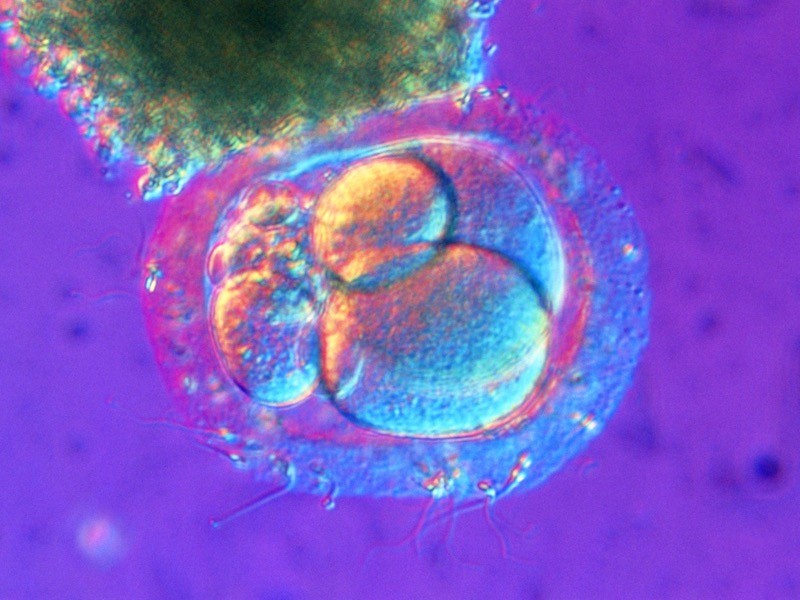

The group, which released its recommendations in two reports on 12 July, was formed after biophysicist He Jiankui, formerly at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China, shocked the world in 2018 by announcing that he had used the CRISPR genome-editing technique to alter embryos that led to the birth of two girls.

Another committee — convened by the US National Academy of Medicine, the US National Academy of Sciences and the UK Royal Society — concluded last September that the technology is not yet ready for use in human embryos (pictured) destined for implantation.

More News

Editorial Expression of Concern: Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase – Nature

Quantum control of a cat qubit with bit-flip times exceeding ten seconds – Nature

Venus water loss is dominated by HCO+ dissociative recombination – Nature