More prestigious institutions often have bigger groups with more staff and students, which can drive greater productivity.Credit: Karen Ducey/Getty

Academics at elite US universities produce more research because they have consistent access to more funded graduate programmes, fellowships and postdocs than do their peers at less prestigious institutions, finds a study that looked at the publication records of nearly 80,000 researchers.

The findings, published in Science Advances on 18 November1, show how having more paid junior researchers and larger research groups drives greater productivity at the most prestigious institutions.

“Faculty who end up at places that are less prestigious don’t have the resources in the form of research labour … then they just produce less science,” says co-author Sam Zhang, a computational social scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The research highlights “inequalities in academia”, says Aaron Clauset, a computer scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, who also worked on the study. He adds that the systems and hierarchies in place “are creating biases that are shifting attention and resources around in ways that are not maybe reflective of our ideals of the meritocracy”.

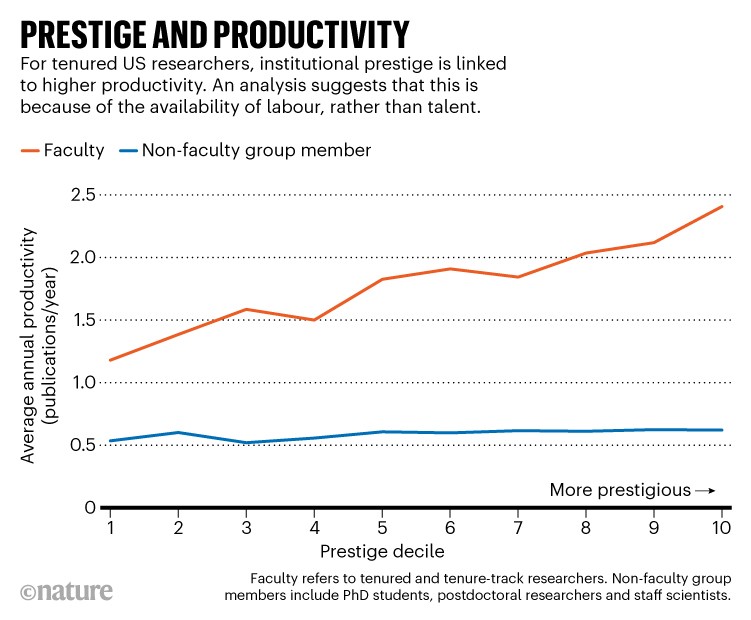

Source: Ref 1

The analysis included 1.6 million publications on the Web of Science database, authored by 78,802 tenured or tenure-track researchers at 262 PhD-granting US universities. The team looked at productivity — defined as the average number of publications authored per year — for both individual researchers and groups. They gave universities a prestige score based on how likely its PhD graduates are to be hired as faculty at another institution.

Although the prestige of an institution does not seem to affect the productivity of graduate students and post-doctoral researchers, the team found that it is linked to increased productivity for tenured or tenure-track faculty members (see ‘Prestige and productivity’).

The team further examined researchers from ‘collaborative’ disciplines — sciences in which research is usually done in groups, as opposed to disciplines in which solitary work is more common, including social sciences, humanities and mathematics. Although faculty members produced more publications in collaborative disciplines compared with other fields, individual researchers’ productivity was nearly identical across all disciplines. This suggests that the higher productivity in elite institutions is due to them having larger research groups and more available labour in collaborative disciplines.

“The myth of the meritocracy, that productivity is tied to some sort of inherent characteristics about a person, doesn’t really seem to be supported by the data,” says Clauset. “Instead, we find these environmental factors that seem to explain differences in average productivity.”

Confounding factors

The researchers acknowledge that there could be other factors associated with university prestige that boost scientists’ productivity. “Funded labour may correlate with things that are characteristic of the elite institutions that are not taken into account in this analysis,” points out Mathias Wullum Nielsen, a sociologist at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. These include “better conditions, better support, better office spaces, less teaching”, he says.

Most US professors are trained at same few elite universities

But the study’s authors think that the effects of available labour are the best explanation for their findings. “These environmental factors cannot explain the pattern we see in faculty group productivity,” says Zhang. “[They] could only confound our labor hypothesis if they selectively improved the group, rather than individual productivity of faculty.”

The paper suggests that if funders support more graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and other staff at less elite institutions, this could reduce some of the inequalities in academia. “Prestige-related factors affect us in our institutions every day,” says Marek Kwiek, who studies research and higher-education policy at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland. “It would be a normative choice to give more funding to people in less prestigious places.”

Kimberly Griffin, a diversity scholar at the University of Maryland in College Park, would like to see further analysis that considers researchers’ genders or ethnicities “not just to [determine] what implications this has for innovation in science, but also what implications this has for diversifying the scientific workforce”.

More News

Retuning of hippocampal representations during sleep – Nature

Measurement of the superfluid fraction of a supersolid by Josephson effect – Nature

Fusion of deterministically generated photonic graph states – Nature