The Iban people knew all along that one tree is actually two

Western science has long considered an Asian tree with the scientific name Artocarpus odoratissimus to be a single species. But a genetic study (E. M. Gardner et al. Curr. Biol. 32, R511–R512; 2022) now confirms that the trees that researchers have been lumping together as A. odoratissimus actually belong to two species — as reflected in the names used by the local Iban people, each of which refers to a distinct variety of the tree.

Artocarpus odoratissimus was first incorporated into Western taxonomy in 1837. In 2016, scientists working in the Malaysian state of Sarawak noticed that local botanists used two names to refer to the tree. Those botanists, who were members of Sarawak’s Indigenous Iban people, called the trees with large fruit and leaves lumok, and those with smaller, less-sweet fruit pingan (pictured, pingan fruit).

To test whether the trees’ DNA reflected this distinction, the researchers compared the genetics of lumok and pingan. The team found that the two tree types were related but distinct enough genetically to be considered separate species. Lumok retains the name A. odoratissimus and pingan has been given the scientific name Artocarpus mutabilis.

Awards named after men less likely to go to women

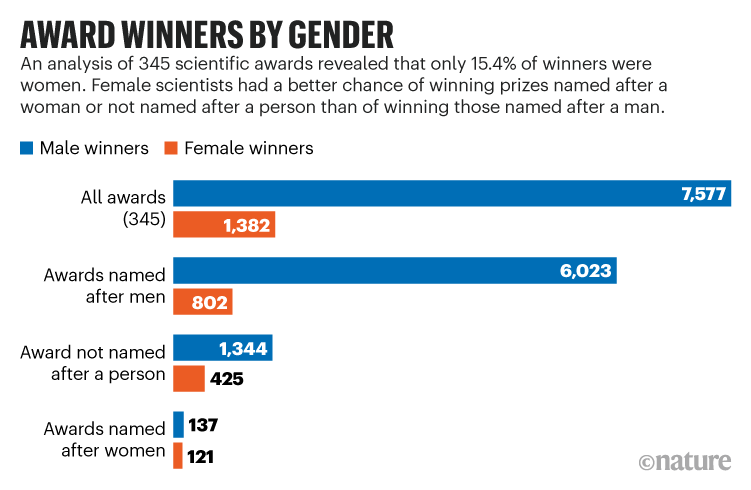

Women are more likely to win awards that aren’t named after a person than to win prizes named after a man, research has found.

The study, presented on 25 May at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) general assembly in Vienna, reviewed almost 9,000 prize recipients across almost 350 awards in the fields of Earth and environmental sciences and cardiology, as well as prizes given out by national scientific bodies in the United Kingdom and United States. The study has yet to be published (S. Krause and K. Gehmlich EGU General Assembly EGU22-2562 https://doi.org/hzn2; 2022).

It found that women have received only around 15% of these awards, going back to the eighteenth century. For the 214 awards that are named after men, female winners fall to just 12% (see ‘Award winners by gender’). But women were the winners 24% of the time for the 93 awards not named after anyone — a trend that was consistent over time, says Stefan Krause, an Earth and environmental scientist at the University of Birmingham, UK, who presented the research at the EGU meeting.

The results suggest that there might be a link between the name of an award and who receives it, he says. “If the awards are not named after a person, the gender balance in prizes is more balanced,” he adds.

US opioid overdose deaths to crest

An opioid crisis in the United States might soon peak and then start to abate, a model suggests (T. Y. Lim et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115714119; 2022).

Since 1999, some 760,000 people in the country have died after overdosing on prescription and illicit opioids, including the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl (pictured, foil used to smoke fentanyl). Treatments such as injections of the drug naloxone, which reverses overdoses, are useful. But the number of deaths continues to rise every year.

Mohammad Jalali, a systems scientist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues collected data on US opioid use and deaths between 1999 and 2020. They built a model that incorporated factors that have changed over the past 20 years, such as the prevalence of fentanyl and the distribution of naloxone. The model relied heavily on feedback loops: an increase in fatal overdoses owing to the presence of fentanyl, for instance, might raise concern in a community and decrease overall use.

The researchers then projected future scenarios. In all of these, they found, overdose deaths are likely to peak before 2025 and then decline. In an ‘optimistic’ scenario, 543,000 people would die between 2020 and 2032, whereas a ‘pessimistic’ one would see 842,000 deaths over this period.

More News

Judge dismisses superconductivity physicist’s lawsuit against university

Future of Humanity Institute shuts: what’s next for ‘deep future’ research?

Star Formation Shut Down by Multiphase Gas Outflow in a Galaxy at a Redshift of 2.45 – Nature