The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 arrived in the fishing community of Andavadoaka, Madagascar, in April this year. At Vezo Hospital, a 17-room clinic that serves Andavadoaka and surrounding areas, a doctor and nurse were the first to test positive, followed by two of the other six medical workers.

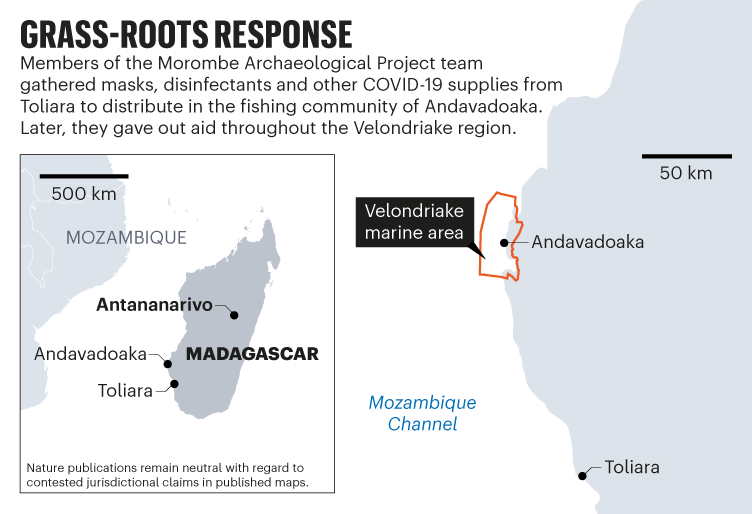

Roughly 200 people in the region, both young and old, displayed symptoms compatible with COVID-19 over a 2-week period, says hospital coordinator Michele Sari. He cannot offer an exact count because the Ministry of Public Health in Madagascar did not provide the tests that would have confirmed cases in the community. Of roughly 3,000 residents, 5 older people died, as well as a 34-year-old fisherman from a neighbouring town. “Everyone was panicking,” says George ‘Bic’ Manahira, who is based in Andavadoaka as field manager for Pennsylvania State University’s Morombe Archaeological Project (MAP), which aims to reconstruct the impact of human settlement in the Velondriake area, a marine protected biodiversity hotspot on the southwest coast of Madagascar.

The first wave of the pandemic hit Madagascar in June last year, but didn’t reach Andavadoaka, sticking mostly to metropolitan areas, where it killed about 230 people. The second wave, however, has reached all corners of the island. It is fuelled by SARS-CoV-2’s Beta variant, citizens’ difficulty in staying at home, and a president, Andry Rajoelina, who does not promote vaccination. So far, Madagascar has received enough COVID-19 vaccine doses for only 1% of its population to receive a single dose, and some doses have been wasted because of hesitancy.

So when SARS-CoV-2 came to Andavadoaka, Manahira knew he couldn’t expect the government to help. Through sheer grit and community organizing, he and a team of MAP archaeologists pivoted from running field surveys to gathering and distributing aid in their town. And when word got out, communities all around the region cried out for help.

A family affair

Throughout the pandemic, Rajoelina has encouraged the citizens of Madagascar to drink a locally brewed plant infusion that he says will protect them and treat coronavirus infections. “It was not proven to be effective,” says Fidisoa Rasambainarivo, co-founder and scientific director of Mahaliana, a laboratory training centre in Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar. “But it was given to schools, and it’s still promoted on TV and at hospitals.”

When the virus arrived in Andavadoaka, Manahira watched families in his community try traditional medicinal plant cures, and knew he needed another solution. He works as a scuba instructor, liaises with community leaders, and oversees MAP’s research team.

In a Zoom lab meeting on 9 April, Manahira described the outbreak to MAP’s director, Penn State archaeologist Kristina Douglass. Raised in Madagascar, Douglass initiated MAP in 2012. The project employs local people — including Manahira and his brother, Zafy Chrisostome, who died this month — and trains them in archaeology and anthropology to run field projects. “Every member of that team feels like a family member to me,” says Douglass, who is based in University Park, Pennsylvania, and has been unable to visit Madagascar during the pandemic.

When Manahira told Douglass about the outbreak, she turned to MAP’s research funding to buy personal protective equipment (PPE) for the community. Penn State approved the request, transferring US$1,500 from her grant to purchase the equipment.

With the money, Manahira organized trucks for an 8-hour drive to Toliara, a coastal town 170 kilometres south of Andavadoaka, to purchase bleach, sprayers and other cleaning products. The MAP team also bought 1,000 cloth masks produced by a sewing group.

Returning to Andavadoaka, the team stopped at every household to distribute supplies. The researchers also shared guidelines about preventing viral transmission, and sprayed disinfectant in community hubs, including the grocery shop, church and schools.

The situation has improved, says Sari: people have stopped arriving at Vezo Hospital with coronavirus symptoms. In fact, the distribution effort was so successful that neighbouring communities reached out, asking for similar aid, says Manahira.

During the pandemic, he says, trade has all but stopped in the region, where communities rely on exporting fish, so people cannot afford to feed their families, much less buy masks. To help, he and Andavadoaka’s deputy mayor, Roger Samba, set a goal of raising $10,000 to provide masks and cleaning supplies to the roughly 320 families in communities near Andavadoaka. Douglass organized an online fundraising campaign, which pulled together the full amount. This enabled Manahira, the MAP team and volunteers from a youth club to distribute more than 10,000 disposable masks, plus disinfectant supplies, in the Velondriake region in April and May.

This kind of hands-on intervention is rare in the area, says Tanjona Ramiadantsoa, an ecologist at the University of Fianarantsoa in eastern Madagascar. Typically, organizations stepping in during a crisis focus on donations and public-relations activities. “What MAP is doing is amazing,” he says. “And it’s sad to hear, because if they’re helping in the southwest, it means it’s raging there and has gone unnoticed by anyone else.”

“MAP’s effort to distribute PPE was really admirable,” says Bram Tucker, an anthropologist at the University of Georgia in Athens who has worked in Madagascar since 1996, and who donated to the effort. “It had real preventative value.”

The intervention was possible because the research team is embedded in the community, says Douglass. “I know many anthropologists and other scientists feel uncomfortable with the idea — that if you form these kinds of deep attachments, that somehow the work you do is less scientific, less rigorous or less objective. But having strong community relationships — especially when they are transparent, mutualistic and reciprocal — improves the quality of the science you do, and they make you ethically more responsible for the outcomes.”

Researchers have an obligation to set science aside for the needs of a community when necessary, says Tucker. “We make careers off our friendships with some of the poorest and least powerful people on Earth. We have an ethical responsibility to do more than just be objective.” The MAP effort is especially industrious, but similar efforts have been and should continue to be undertaken by research groups in other countries, especially in anthropology circles, says Tucker.

The next chapter

MAP’s next goal is to facilitate vaccination, says Manahira. But first, he is organizing surveys to see who in the Andavadoaka region, if anyone, is willing to get the vaccine. If enough people want a jab, the team will raise funds to hire a helicopter to bring in doses. But there hasn’t yet been enough interest. This seems to be a pattern around the country. Madagascar received 250,000 doses of AstraZeneca’s Covishield vaccine in May through the COVAX programme — an alliance of international organizations that aims to distribute vaccines to low- and middle-income countries — but health officials administered only 190,000 of the doses before they expired on 17 June, because not enough people turned up to receive them.

Michel Saint-Lot, a representative of the development and humanitarian aid organization UNICEF Madagascar, anticipates another vaccine shipment from COVAX in August, which will be necessary for vaccinated individuals to get their second dose. “We’re confident these things can be overcome, and we’ll step up the campaign,” he says. “We hope the full government will join us to get the country immunized.”

Covishield has not proved as effective against the Beta variant as have other vaccines1, but it’s still something, says Rasambainarivo. “Any vaccine is better than no vaccine at all.”

According to government reports, coronavirus cases across Madagascar have been in decline since late April. By mid-June, 56% of hospital beds were available for people with illnesses other than COVID-19, says Saint-Lot, and UNICEF is working with the government and other partners to prepare for any further waves of infection by restocking supplies such as testing kits, PPE, and oxygen, and getting health-care staff vaccinated.

Yet government reports might indicate the situation only in metropolitan areas, where most COVID-19 testing is done, says Rasambainarivo. “It is not necessarily in other regions, which have effectively been invisible.”

In Andavadoaka, Manahira continues to receive daily phone calls and texts from people who live hours away, requesting masks and disinfectant.

More News

Could bird flu in cows lead to a human outbreak? Slow response worries scientists

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

How high-fat diets feed breast cancer